تاريخ الرياضيات

تاريخ الرياضيات

الرياضيات في الحضارات المختلفة

الرياضيات في الحضارات المختلفة

الرياضيات المتقطعة

الرياضيات المتقطعة

الجبر

الجبر

الهندسة

الهندسة

المعادلات التفاضلية و التكاملية

المعادلات التفاضلية و التكاملية

التحليل

التحليل

علماء الرياضيات

علماء الرياضيات |

Read More

Date: 11-1-2016

Date: 30-12-2015

Date: 1-1-2016

|

The number system most commonly used today is based on the Hindu Arabic number system, which was developed in what is now India around 300 B.C.E. The Arab mathematicians adopted this system and brought it to Spain, where it slowly spread to the rest of Europe.

The present-day number system, which is called the decimal or base -10 number system, is an elegant and efficient way to express numbers. The rules for performing arithmetic calculations are simple and straightforward.

Basic Properties

The decimal number system is based on two fundamental properties. First, numbers are constructed from ten digits, or numerals—0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, and 9—that are arranged in a sequence. Second, the position of a digit in the sequence determines its value, called the place value. Because each digit, by its place value, represents a multiple of a power of 10, the system is called base-10.

Numbers Greater and Less Than One.

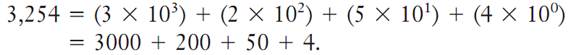

The expansion of numbers greater than 1 consists of sums of groups of tens. Each digit in the expansion represents how many groups of tens are present. The groups are 1s, 10s, 100s, and so on. The groups are arranged in order, with the right-most representing 100 , or groups of 1s. The next digit to the left in the group stands for 101 , or groups of 10s, and so on. For example, the expansion of the whole number 3,254 in the decimal system is expressed as:

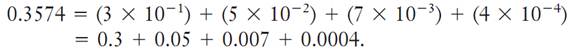

A number less than 1 is represented by a sequence of numbers to the right of a decimal point. The digits to the right of a decimal point are multiplied by 10 raised to a negative power, starting from negative 1. In moving to the right, the place value decreases in value, each being one-tenth as small as the previous place value. Thus, each successive digit to the right of the decimal point denotes the number of tenths, hundredths, thousandths, and so forth. For example, the expansion of 0.3574 is expressed as:

Decimal Fractions.

The example above illustrates standard decimal notation for a number less than 1. But what is commonly referred to as a decimal is actually a decimal fraction. A decimal fraction is a number written in decimal notation that does not have any digits except 0 to the left of the decimal point. For example, .257 is a decimal fraction, which can also be written as 0.257. It is preferable to use 0 to the left of the decimal point when there are no other digits to the left of the decimal point.

Decimal fractions can be converted into a fraction using a power of 10.

For example, 0.486 = 486/1000, and 0.35 = 35/100. The fraction may be convertedto an equivalent fraction by writing it in its simplest or reduced form. The fraction 35/100equals 7/20, for example.

Decimal Expansion of Rational and Irrational Numbers

Is it possible to convert all fractions into decimals and all decimals into fractions? All fractions, a/b, are rational numbers, and all rational numbers are fractions, provided b is not 0. So the question is: Can every rational number be converted into a decimal?

Taking the rational number, or fraction a/b, and dividing the numerator by the denominator will always produce a decimal. For example, 1/4= 0.25, 1/10= 0.1, and 2/5= 0.4. In each of these examples, the numbers to the right of the decimal point end, or terminate.

However, the conversion of 1/3= 0.333. . ., 2/9= 0.222. . ., and 3/11=0.2727. . ., results in decimals that are nonterminating. In the first example, the calculation continuously produces 3, which repeats indefinitely. In the second example, 2 repeats indefinitely. In the third example, the pair of digits 2 and 7 repeats indefinitely.

When a digit or group of digits repeats indefinitely, a bar is placed above the digit or digits. Thus, 1/3 =0.3, 2/9= 0.2, and 3/11= 0.2 7.

These are exam-ples of repeating but nonterminating decimals.

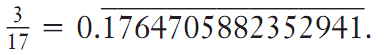

It may not always be apparent when decimals start repeating. One interesting example is 3/17. The division needs to be carried out to sixteen digits before the repeating digits appear:

Nonterminating and nonrepeating decimal numbers exist, and some may have predictable patterns, such as 0.313113111311113. . .. However, these numbers are not considered rational, but instead are known as irrational. An irrational number cannot be represented as a decimal with terminating or repeating digits, but instead yields a nonterminating, nonrepeating sequence. A familiar example of an irrational number is √2, which in decimal form is expressed as 1.414213. . ., where the digits after the decimal point neither end nor repeat. Another example of an irrational number isπ, which in decimal form is expressed as 3.141592. . . .

Daily Applications of Decimals

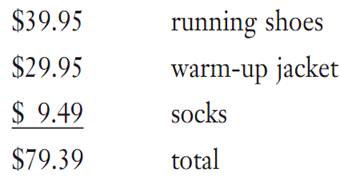

In daily use, decimal numbers are used for counting and measuring. Consider a shopping trip to a sporting good store, where a person buys a pair of running shoes, a warm-up jacket, and a pair of socks. The total cost is calculated by aligning at the right all three numbers on top of each other.

As another example, consider a car’s gas tank that has a capacity of 18.5 gallons. If the gas tank is full after pumping 7.2 gallons, how much gasoline was already in the tank? The answer is 18.5 minus 7.2, which equals 11.3 gallons.

______________________________________________________________________________________________

Reference

Amdahl, Kenn, and Jim Loats. Algebra Unplugged. Broomfield, CO: Clearwater Publishing Co., 1995.

Dugopolski, Mark. Elementary Algebra, 3rd ed. Boston: McGraw-Hill, 2000.

Dunham, William. The Mathematical Universe. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 1994.

Miller, Charles D., Vern E. Heeren, and E. John Hornsby, Jr. Mathematical Ideas, 9th ed. Boston: Addison-Wesley, 2001.

|

|

|

|

تفوقت في الاختبار على الجميع.. فاكهة "خارقة" في عالم التغذية

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

أمين عام أوبك: النفط الخام والغاز الطبيعي "هبة من الله"

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

قسم شؤون المعارف ينظم دورة عن آليات عمل الفهارس الفنية للموسوعات والكتب لملاكاته

|

|

|