تاريخ الرياضيات

تاريخ الرياضيات

الرياضيات في الحضارات المختلفة

الرياضيات في الحضارات المختلفة

الرياضيات المتقطعة

الرياضيات المتقطعة

الجبر

الجبر

الهندسة

الهندسة

المعادلات التفاضلية و التكاملية

المعادلات التفاضلية و التكاملية

التحليل

التحليل

علماء الرياضيات

علماء الرياضيات |

Read More

Date: 22-10-2015

Date: 22-10-2015

Date: 22-10-2015

|

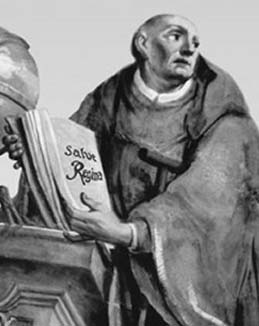

Born: 18 July 1013 in Saulgau, Swabia, Germany

Died: 24 September 1054 in Reichenau, Germany

Hermann of Reichenau is also called Hermann the Lame or Hermannus Contractus. His parents were Count Wolverad II von Altshausen-Veringen and his wife Hiltrud. They were a noble family from Upper Swabia, a district north of the Bodensee (also known as Lake Constance). The lake has a western arm, west of the city of Konstanz, and in this is situated the island of Reichenau. This island, about 5 km long and 1.5 km wide, was the artistic and literary centre of south west Germany during this period and was the site of a famous Benedictine monastery which had been founded there in 724. This monastery, along with several other Benedictine monasteries, played an important role in scholarship since it was a centre where manuscripts were copied. Historians seem almost equally divided between those who believe that Hermann was born in Saulgau and those who believe he was born in his father's castle, Castle Altshausen, in Altshausen.

Hermann of Reichenau is also called Hermann the Lame or Hermannus Contractus. His parents were Count Wolverad II von Altshausen-Veringen and his wife Hiltrud. They were a noble family from Upper Swabia, a district north of the Bodensee (also known as Lake Constance). The lake has a western arm, west of the city of Konstanz, and in this is situated the island of Reichenau. This island, about 5 km long and 1.5 km wide, was the artistic and literary centre of south west Germany during this period and was the site of a famous Benedictine monastery which had been founded there in 724. This monastery, along with several other Benedictine monasteries, played an important role in scholarship since it was a centre where manuscripts were copied. Historians seem almost equally divided between those who believe that Hermann was born in Saulgau and those who believe he was born in his father's castle, Castle Altshausen, in Altshausen.

Hermann is called 'the Lame' or 'Contractus' for very good reason. He was extremely disabled from childhood, having only limited movement and limited ability to speak. He had a special chair made for him and he had to be carried around. One of the most recent studies of his illness is the article [5] by Brunhölzl where there is an attempt to use the available evidence to make a modern diagnosis:-

Hermann from Reichenau - Hermannus contractus - apparently suffered from a disease which led to considerable physical handicap leaving his outstanding intellectual talents undamaged. Various statements about his condition - an epileptic, suffering from spasticity, afflicted by poliomyelitis - have never been reconsidered. Using the biography written by his disciple Berthold, the most important contemporary source about Hermann's life, an approach to a correct diagnosis from a neurologists point of view was the aim of this study. By unbiased analysis of the symptoms described by Berthold a neurologic syndrome is worked out: it comprised a flaccid tetraparesis involving the bulbar area. The sensory as well as the autonomic nervous system were apparently not involved. Intellectual functions were unaffected. Considering this syndrome and other details of Hermann' life as well as the beginning and course of his illness, a traumatic birth injury, an early childhood disease and a central nervous as well as an infectious disease are ruled out. Muscle disease is considered possible, but motor neuron disease - either amyotrophic lateral sclerosis or spinal muscular atrophy - seems to be the most convincing diagnosis.

Hermann entered the Cloister School at Reichenau, attached to the monastery, on 13 September 1020 and studied there under the Abbot Berno (about 978-1048). The monastery was a centre of learning at this time, containing a fine library and a well-equipped workshop. Hermann became a monk at the Benedictine Monastery at Reichenau in 1043, later becoming Abbot of the Monastery after the death of Abbot Berno on 7 June 1048. Despite his disabilities, being confined to a chair and hardly able to speak, he was a key figure in the transmission of Arabic mathematics, astronomy and scientific instruments from Arabic sources into central Europe. In other words he published in Latin much scientific work which before this time had been only available in Arabic. One would expect, from this description, that he would be an Arabic speaker but it is thought almost certain that he could not read Arabic. His pupil Berthold of Reichenau, from whom we have the details of Hermann's life, does not mention that he could read Arabic and, given the nature of Berthold's writings about his master, it would be highly unlikely that he would not have mentioned this ability if indeed Hermann had been knowledgeable in the Arabic language. However, Gerbert of Aurillac, who died ten years before Hermann was born, had learnt much from Arabic sources in Spain and had written several works which, almost certainly, would have found their way to the monastery at Reichenau.

Hermann introduced three important instruments into central Europe, knowledge of which came from Arabic Spain. He introduced the astrolabe, a portable sundial and a quadrant with a cursor. The portable sundial is described by Lynn Thorndike in [14]. It consists:-

... of an upright cylinder with a conical top terminating in a knob by which it might be turned, with a vertical scale to the right of the cylinder and obliquely curving lines across the face of the cylinder which are to trace the sun's shadow. Apparently these instruments were used to determine the latitude as well as to find the hour and the altitude of the sun, or at least they were adapted to determine the hour in different places and latitudes where a traveller might be.

His works include De Mensura Astrolabii and De Utilitatibus Astrolabii. Some parts of these works may not have been written by Hermann and the most likely author on which they are based must be Gerbert of Aurillac. The description of the astrolabe that Hermann gives is for an instrument which is designed to be used at a latitude of forty-eight degrees, which is indeed the latitude of Reichenau. These works contain more than just a description of the astrolabe, however, for they also contain star charts (again with data correct for the latitude of Reichenau) and a calculation of the earth's diameter. This calculation, following Eratosthenes' method and data, uses π = 22/7 in the working.

Hermann's contributions to mathematics include a treatise Qualiter multiplicationes fiant in abbaco dealing with multiplication and division, although this book is written entirely with Roman numerals. Florence Yeldham describes in [15] manuscripts based on the work of Hermann:-

The Cathedral Library at Durham possesses an unnoticed early twelfth-century manuscript of English provenance of a work, hitherto unrecorded, of Hermannus Contractus. It contains the multiples, products, and quotients of the duodecimal fractions. The manuscript, when first found by Dr Singer in February, 1927, was pasted on linen and very roughly nailed to a wooden frame .... Dr Singer obtained permission for the manuscript to be sent to London to be studied by me and to be put into good order. When I examined it in April, 1927, I found that the ink was rubbed and worn in parts and that in one place a large piece of vellum was lost. The greater part of the chart, however, had escaped damage and I recognized its likeness to certain pages of another twelfth-century manuscript on which I had been working. A closely similar, and also undescribed, set of tables is, in fact, to be found in a manuscript of English origin written in or about the year 1111 A.D. and now in the library of St John's College, Oxford. Both the St John's and the Durham tables use the Roman notation and fraction symbols. They are arranged with great economy of space and are handy to use. This is especially the case in the Durham chart, in which the multiplicands, multipliers, divisors, and dividends stand out clearly in alternate red and green, while the multiples, products, and quotients are smaller and in black. This chart is ruled in double lines of red and green, meeting in one corner in a grotesque drawing of a lion's head.

He also wrote on a complicated game based on Pythagorean number theory which was derived from Boethius. It appears in De conflictu rithmimachie [1]:-

The game was played with counters on a board; capture of the opponent's pieces was dependent on the determination of arithmetical ratios and arithmetic, geometrical, and harmonic progressions. This game, which enjoyed a considerable vogue during the Middle Ages, has been attributed to Pythagoras, Boethius, and Gerbert.

Another interesting piece of work by Hermann is on lunar months. Around 1040 he wrote Epistola de quantitate mensis lunaris which addressed the problem of the lengths of the lunar month. It was known that the moon and the sun essentially returned to the same position after a cycle of 19 years. Now 19 years contains 6939.75 days and 235 lunar months. To make the lunar calendar work, therefore, requires that the average length of a month across the 19 year cycle is

6939.75/ 235 = 29.530851 days.

Of course, Hermann did not have the decimal notation we have just used in this calculation. He had units of time which divided a day into 24 hours, an hour into 40 moments, and a moment into 564 atoms. His calculation of the average length of the lunar month in each 19 year cycle came out to

29 days 12 hours 29 moments 348 atoms.

If you do a little arithmetical calculation, you'll see that Hermann was exactly right. He used this value for the average length of the month to create a new lunar calendar in Abbreviato compoti (1042).

Hermann also wrote on music, considered as a part of mathematics at this time. His work has been studied in depth by several authors, and in particular we refer the reader to the fascinating article by Richard Crocker [8]. Crocker begins that article by quoting from Hermann's Opuscula musica. Hermann had learnt musical theory from his teacher Berno who, having reformed the Gregorian chant into eight modes called 'tones', was probably the leading music expert in his day. Hermann wrote:-

To begin with, let us look at one rule for recognizing the modes which has hitherto been dug out as a rough mass, so to speak, by previous writers, but not fully worked clear of dross, and let us state it in such a way that it may stand forth clear and pure for earnest students. This matter of recognition, to be sure, though it may be reduced to a brief statement, is nevertheless extensive and notable in character, since that which is very elegantly indicated in it finds a place among the proper and rightful foundations of the modes.

Crocker writes [8]:-

Hermann, starting from the emphasis laid by his teacher Berno of Reichenau on the species of fourths and fifths, first relied on them to mediate the anomalies between the recurring tetrachord of the finals and the scale of the 'Dialogus', then eventually came to the same major sixth. And in Hermann's discussion, this major sixth so strongly resembles the hexachord that it seems the two should be identified without hesitation.

Not only did Hermann write on the theory of music but he also wrote poetry and hymns. His best known hymn is Salve Regina and he is also believed to have written Veni Sancte Spiritus and the Easter hymn Alma Redemptoris mater. It is always difficult to be certain that the attribution of works from this early period is correct and, indeed, many scholars doubt whether these hymns have come down to us in the same form as Hermann wrote them. There seems little doubt, however, that even if these works have been modified later, they are based on hymns written by Hermann. A poem about the eight deadly sins, written for the nuns at Buchau, shows that Hermann had an excellent sense of humour.

Finally, let us note Hermann's important contributions to history. He wrote Chronicon ad annum 1054 which no longer exists in the original manuscript but did survive long enough to be printed by J Sichard at Basel in 1529. Numerous later editions have been published of this important historical work which contains unique information about Henry III (1017-1056), duke of Bavaria (1027-41), duke of Swabia (1038-45), German king (1039-56), and Holy Roman emperor (1046-56).

In his historical chronicle, Hermann records the death of his own mother Hiltrud in 1052. He wrote an inscription for his mother's grave in Altshausen which shows his deep love and devotion to her. He requested that he be buried beside his mother and, only two years later, this remarkable man died and his wishes were carried out. He had requested that his disciple, Berthold of Reichenau, should take wax tablets on which his writings were recorded and have these made into manuscripts. Indeed, it is because Berthold faithfully carried out Hermann's request that so much of Hermann's work was preserved. Hermann also requested that Berthold continue to record the chronicle which he had taken as far as the year 1054. He certainly did continue the chronicle but there is some doubt as to how far he continued it since we know that it was later extended by others. Several authors saw the chronicle continue up to the year 1175 and it appears that Berthold died in 1088.

Books:

Articles:

|

|

|

|

لمكافحة الاكتئاب.. عليك بالمشي يوميا هذه المسافة

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

تحذيرات من ثوران بركاني هائل قد يفاجئ العالم قريبا

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

العتبة العباسية تشارك في معرض النجف الأشرف الدولي للتسوق الشامل

|

|

|