Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension|

Read More

Date: 2023-12-18

Date: 14-1-2022

Date: 2023-10-28

|

As we saw, the same phoneme may be realized in different environments by more than one allophone. Interestingly, a single morpheme may likewise have several allomorphs. A good example is provided by regular plurals in English:

bat+s ‘bats’

dog+s ‘dogs’

place+s ‘places’

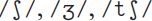

At first sight, this looks like a highly regular pattern of inflection, in which plurals are formed by adding -s to the singular noun. But the orthography disguises the fact that the three endings here are different: /S/ for the first, /Z/ for the second and /IZ/ for the last. The three allomorphs are, furthermore, in complementary distribution: /S/ is used after voiceless consonants (e.g. caps, bets, bricks, coughs), /Z/ after voiced ones (beds, ribs, logs, lathes) and /IZ/ after the sibilants or ‘hissing sounds’ /S/, /Z/,  and

and  (mazes, wishes, matches). We can describe /S/, /Z/ and /IZ/ as three allomorphs of the morpheme <PLURAL>, although we should note here that we are using ‘morpheme’ here in a slightly more abstract sense than hitherto: to avoid terminological confusion where the distinction is important some linguists reserve the term ‘morpheme’ for the abstract representation of a particular grammatical value (e.g. <PLURAL>for the category of ‘number’), and use the term morph (or allomorph) for its actual realization.

(mazes, wishes, matches). We can describe /S/, /Z/ and /IZ/ as three allomorphs of the morpheme <PLURAL>, although we should note here that we are using ‘morpheme’ here in a slightly more abstract sense than hitherto: to avoid terminological confusion where the distinction is important some linguists reserve the term ‘morpheme’ for the abstract representation of a particular grammatical value (e.g. <PLURAL>for the category of ‘number’), and use the term morph (or allomorph) for its actual realization.

More serious problems do, however, beset the morpheme concept in the case of what are termed discontinuous morphemes. Consider the following irregular plurals in English:

mouse – mice

foot – feet

tooth – teeth

man – men

louse – lice

Though this fact is somewhat disguised by the orthography in the case of louse/lice and mouse/mice, all these examples involve monosyllabic items in which a vowel change occurs in the nucleus position in the plural, but the onset and coda are left unchanged. One might therefore wish to posit a discontinuous root morpheme in each case, i.e. /m_s/ for mouse and /f_t/ for foot. Though this might appear to be stretching a point, it is not in fact implausible: in Semitic languages, for example, a number of related words share a common root in which the vowels change, as illustrated by the root k_t_b in Arabic:

Similarly, in German regular past participle forms involve a prefix ge- and a suffix -t (e.g. gelernt, from the verb lernen in ‘Ich habe gelernt’ – ‘I have learned’). But even if one is prepared to extend the morpheme concept to discontinuous elements, a problem remains with our English plurals, namely how are we to analyze <PLURAL> in these words?

A first, obvious difficulty is that there is no meaningful sense in which these forms can be analyzed as a noun+plural marker sequence: the vowel change which marks plurality is not a suffix. Secondly, whereas with regular plurals a plural morpheme is added (we can include zero plurals here), these plural forms involve a change rather than an addition. One solution might be to describe the <PLURAL> allomorph in mice as a process  , but this seems to bend the original concept of the morpheme as ‘minimal meaning bearing unit’ beyond all recognition without any compensatory gains in terms of descriptive power or elegance. It seems better simply to view these plurals as a non-productive subset of English nouns – in fact a vestige of the umlaut process which survives in German, for example in der Vogel (sg. ‘the bird’) – die Vögel (‘the birds’).

, but this seems to bend the original concept of the morpheme as ‘minimal meaning bearing unit’ beyond all recognition without any compensatory gains in terms of descriptive power or elegance. It seems better simply to view these plurals as a non-productive subset of English nouns – in fact a vestige of the umlaut process which survives in German, for example in der Vogel (sg. ‘the bird’) – die Vögel (‘the birds’).

The morpheme-to-meaning relationship also breaks down in the Celtic languages, where gender agreement is marked by mutation of initial consonants, as in the following examples from Breton:

ar paotr bras ‘the big lad’

an daol vras ‘the big table’

ul levr kozh ‘ an old book’

un gador gozh ‘an old chair’

A mutation known as lenition affects some (but not all) initial consonants of singular feminine nouns after articles (thus taol ‘table’ becomes daol; and kador ‘chair’ becomes gador, but the masculines paotr ‘lad’ and levr ‘book’ are unchanged), and the initial consonant of an adjective qualifying a feminine noun (contrast bras/vras ‘big’, and kozh/gozh ‘old’). Mutation in Breton exemplifies what is known as non-concatenative morphology in that, in contrast to the Turkish examples, nothing is actually added to a stem (calling -aol a ‘stem’ is an unsatisfactory solution because many other Breton words have initial consonants which are unaffected by mutation) and, as was the case for the exponents of <PLURAL> in the forms feet, mice, etc. in English, we cannot identify a morpheme which marks gender.

|

|

|

|

كل ما تود معرفته عن أهم فيتامين لسلامة الدماغ والأعصاب

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

ماذا سيحصل للأرض إذا تغير شكل نواتها؟

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

بالتعاون مع العتبة العباسية مهرجان الشهادة الرابع عشر يشهد انعقاد مؤتمر العشائر في واسط

|

|

|