Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension|

Read More

Date: 2023-11-09

Date: 2024-06-05

Date: 2024-03-20

|

The environment for SVLR

If LLL and SVLR do co-exist in SSE and Scots dialects, they must be individually characterized. In fact, each has a distinct input and environment: LLL applies to all vowels before all voiced consonants and word finally (or, perhaps more accurately, pre-pausally), while SVLR is much less general, affecting only a subset of the vowel system, before voiced fricatives, /r/ and ], the bracket used in Lexical Phonology to replace traditional word and morpheme boundary. We established and formulated the input conditions for SVLR, and must now attempt to characterize the environment more satisfactorily. To do so, we must address the question of why vowel lengthening should occur preferentially in these particular SVLR contexts.

In universal terms, the relevant factors determining length seem to be voicing, and the different rates of transition between adjacent vowel and consonant closures: `with stop consonants, the closure transition from a preceding vowel is shorter, since the achievement of a stricture of complete closure does not require the same degree of muscular control as that required for a fricative' (Harris 1985: 121). Harris therefore proposes a consonant scale from voiceless non-continuants at the extreme left, which do not lengthen vowels, to voiced continuants, which most affect the duration of preceding vowels, at the extreme right.

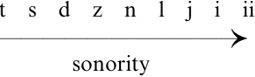

Ewen's (1977) Dependency Phonology formulation of the synchronic SVLR, and Vaiana Taylor's (1974) statement of the historical rule both rely on similar strength or sonority hierarchies. However, Harris (1985: 91) points out a number of problems with this interpretation of SVLR lengthening as `preferential strengthening'. Most importantly, Vaiana Taylor's sonorance scale does not differentiate /l/ from /r/, and excludes nasals (which, according to similar sonority hierarchies proposed by Vennemann and Hooper, for instance, should be intermediate between voiced fricatives and liquids). On Ewen's syllabicity hierarchy, the elements involved in SVLR (i.e. vowels, liquid /r/ and voiced fricatives) similarly form a discontinuous sequence. The prediction of a typical sonority scale of the sort in (1) is therefore that lengthening should affect vowels in the context of nasals and liquids before it affects them in the environment of voiced fricatives, and this is certainly not the case for SVLR.

(1)

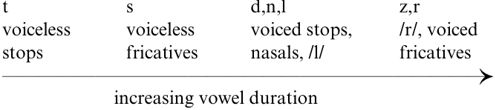

However, Harris's voicing and continuance scale does seem to permit a positioning of nasals and /l/ which accounts for their status as long contexts for LLL but as short contexts for SVLR. Harris (1985: 122) classifies the nasals with the voiced stops on the grounds that `the oral gesture required for nasal stops is the same as that required for oral stops, i.e. an abrupt, ballistic movement appropriate for a stricture of complete closure. This manner of articulation ... favors a shorter duration of preceding vowels. Hence nasals are Aitken's Law ``short'' environments.'

Harris separates the liquids by analyzing /l/ as [- continuant] and /r/ as [+ continuant], citing cross-linguistic evidence that /l/ typically patterns with non-continuant segments. Although Chomsky and Halle (1968) initially classify all liquids as continuants, they recognize this as problematic. As Harris (1985: 123) points out, the difficulty disappears if the articulation of non-continuants is taken to involve a blockage of the airflow along the sagittal plane of the oral tract. This redefinition is now fairly standard, giving a combined voicing and continuancy scale as shown in "Low-Level Lengthening (1)" earlier, repeated as (2).

(2)

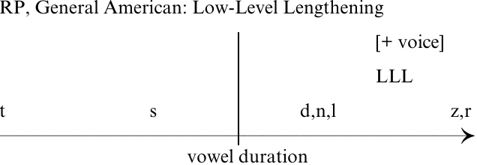

The environments for SVLR and LLL are readily statable in relation to this scale. In RP and GenAm, the one relevant lengthening rule applies progressively before all voiced consonants, both continuants and non-continuants; that is, everywhere to the right of the vertical line in (3), and with even greater length pre-pausally, although the scale has been restricted at present to consonantal environments.

(3)

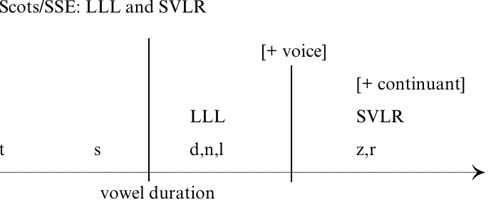

In Scots, this rule also applies, in the same environments, but SVLR also operates before voiced continuants, thus on the right of the right most vertical line in (4).

(4)

It is interesting to note (Nigel Vincent, personal communication) that a similar generalization of allophonic vowel lengthening, but in the opposite direction, is taking place in Modern French, where older speakers have long vowels before the voiced continuants /v z Ʒ ʁ/, giving long-short alternations in pairs like vif (m.) ~ vive (f.) `lively', but younger speakers also have long vowels before voiced stops, as in vague `wave', robe `dress'.

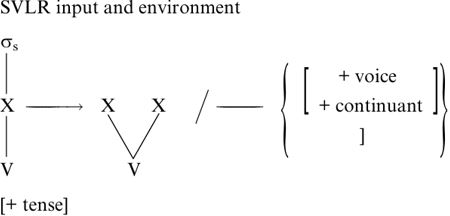

We can now formulate the SVLR environment in feature terms as in (5).

(5)

|

|

|

|

التوتر والسرطان.. علماء يحذرون من "صلة خطيرة"

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

مرآة السيارة: مدى دقة عكسها للصورة الصحيحة

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

نحو شراكة وطنية متكاملة.. الأمين العام للعتبة الحسينية يبحث مع وكيل وزارة الخارجية آفاق التعاون المؤسسي

|

|

|