تاريخ الرياضيات

تاريخ الرياضيات

الرياضيات في الحضارات المختلفة

الرياضيات في الحضارات المختلفة

الرياضيات المتقطعة

الرياضيات المتقطعة

الجبر

الجبر

الهندسة

الهندسة

المعادلات التفاضلية و التكاملية

المعادلات التفاضلية و التكاملية

التحليل

التحليل

علماء الرياضيات

علماء الرياضيات |

Read More

Date: 9-6-2017

Date: 19-6-2017

Date: 13-6-2017

|

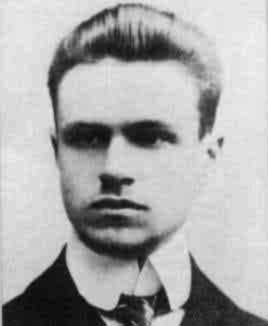

Died: 3 January 1920 in Lvov, Poland (now Lviv, Ukraine)

Zygmunt Janiszewski's mother was Julia Szulc-Chojnicka. His father, Czeslaw Janiszewski, was a graduate of the University of Warsaw and was an important person in finance, being the director of the Société du Crédit Municipal in Warsaw. After attending secondary school in Warsaw, Janiszewski decided to go abroad for a university education. This was the typical route for Poles at this time, and we shall give some background to explain why this was so.

The first thing to note is that when Janiszewski graduated from secondary school in 1907, Poland did not formally exist. Poland had been partitioned in 1772 and the south was called Galicia and under Austrian control. Russia controlled much of the rest of the country and in the years prior to Janiszewski's birth there had been strong moves by Russia to make "Vistula Land", as it was called, be dominated by Russian culture. In a policy implemented between 1869 and 1874, all secondary schooling was in Russian. Warsaw only had a Russian language university after the University of Warsaw was closed by the Russian regime in 1869. Galicia, although under Austrian control, retained Polish culture and was often where Poles from "Vistula Land" went for their education. Janiszewski, however, decided to go to Zurich for his university education. In Zurich he was part of a group of Polish students which he organised, showing organisational skills which would become evident of a wider scale later in his life.

After studying mathematics for a year at Zurich and spending a short time in Munich, Janiszewski went to Göttingen to continue his studies. Having chosen excellent centres of mathematical research at which to study he was taught by many outstanding mathematicians including Burkhardt, Hilbert, Minkowski, and Zermelo

Janiszewski next went to one of the other leading centres of mathematics in the world, namely Paris. There his professors included Goursat, Hadamard, Lebesgue, Émile Picard, and Poincaré. Lebesgue supervised Janiszewski's doctoral studies in topology and in 1911 he submitted his thesis Sur les continus irréductibles entre deux points. The examining board for his doctoral thesis was an extremely powerful group of mathematicians, Poincaré, Lebesgue and Fréchet.

Janiszewski returned to Congress Poland (the Russian controlled region) and taught for a while in Warsaw; not at the University of Warsaw for this had been closed in 1869 as we noted above. In 1913 he published a paper of fundamental importance On cutting the plane by continua. This paper both won for him the J Mianowski Foundation prize and also qualified him to teach at the University of Lvov. There he taught courses on analytic functions and functional calculus. On 11 July 1913 he delivered his important lecture on the axiom of choice which was published in 1916 as On realism and idealism in mathematics (the realists did mathematics without the axiom of choice, while the idealists accepted the axiom).

He continued to teach at Lvov until the outbreak of World War I when he enlisted in the Polish legion. The position of Poland when war broke out was rather complicated. On 16 August 1914, the Austrian government had allowed the organisation of the Polish legion which Janiszewski joined. He joined because he believed that the legion was fighting for Polish independence. However, the Austrians aim was to incorporate Congress Poland into Galicia, the region in which Lvov was situated. Russia tried to win Polish support, particularly in Galicia, by promising the Poles autonomy. By the end of 1914 Russian forces controlled almost all of Galicia.

The Central Powers (Germany and Austria- Hungary) recaptured Galicia and large parts of Congress Poland. A German governor general was installed in Warsaw and a new Kingdom of Poland was declared on 5 November 1916. The Polish volunteer troops in the Polish legion, however, were not satisfied with the Austrian-German declaration which left them with a tiny Poland compared to pre-1772 country. When the men in the Polish legion were required to take an oath of loyalty to the Austrian government this became too much for loyal Poles like Janiszewski. He left the legion and hid under the false name of Zygmunt Wicherkiewicz in Boiska near Zwolen.

From Boiska he moved on to Ewin, near Wloszczowa, where he directed a refuge for homeless children. The University of Warsaw had become Polish again in November 1915 and before Janiszewski left Ewin he already had links to the university. He now became a professor at the University of Warsaw.

Kuratowski attended seminars given by Janiszewski in Warsaw before the end of the war. He writes in [3]:-

As early as 1917 [Janiszewski and Mazurkiewicz] were conducting a topology seminar, presumably the first in that new, exuberantly developing field. The meeting of that seminar, taken up to a large extent with sometimes quite vehement discussions between Janiszewski and Mazurkiewicz, were a real intellectual treat for the participants.

At the end of the war it was Janiszewski who was the main force in the remarkable creation of one of the strongest schools of mathematics in the world. It is all the more remarkable given the position in which Poland found itself at the end of the war. Kuratowski explains in [3] the importance of Janiszewski's vision :-

In the first volume of [Polish Science: Its Needs, Organisation, and Development], which appeared in 1918, Janiszewski published an article "On the needs of mathematics in Poland", which with amazing clarity and precision presented a blueprint for Polish mathematics. Janiszewski started out with the assumption that Polish mathematicians do not have to be satisfied with the role of followers and customers of foreign mathematical centres but can achieve an independent position for Polish mathematics. One of the best ways of achieving this goal, suggested Janiszewski, was for groups of mathematicians to concentrate on relatively narrow fields in which Polish mathematicians had common interests and - more importantly - had already made internationally important contributions. These areas included set theory, and the foundations of mathematics.

In fact these were exactly the areas in which Janiszewski himself had already made internationally important contributions. In addition to set theory (which at that time included parts of what we call topology today) Janiszewski produced important results in the foundations of mathematics and other parts of topology.

Janiszewski saw that mathematics was one scientific subject where Poland could rapidly reach a leading role, whereas other sciences required a much larger financial investment which Poland was not then in a position to give. He wrote in his article (see for example [2]):-

It is true that a mathematician does not require laboratories of complex and expensive auxiliary devices.

His mathematical contributions, relatively few because of the little time he had to apply himself to research in his short life, are none the less of major importance. His doctoral thesis contains important results on closure properties. He gave a topological characterisation of the plane which simplified considerably the Jordan curve theorem. His paper to the International Mathematical Congress in Cambridge in England in 1912 was of major importance for it sketched the definition of a curve without arcs, so that it had no homeomorphic images of a segment of a straight line. His mathematical contributions are considered in more detail in [1].

Janiszewski played a major role in the setting up of the journal Fundamenta Mathematicae and Kuratowski recalls that it was Janiszewski who proposed the name of the journal in 1919. The first volume appeared in 1920 and, although the intention was for a truly international journal, Janiszewski had quite deliberately decided to make the first volume contain papers by Polish authors only. He wrote (see for example [3]):-

... it is my intention to present, if possible, all Polish mathematicians working in the field of set theory, to which the journal is devoted.

It was an immeasurable loss to mathematics when Janiszewski died during an influenza epidemic. The epidemic spread throughout Europe and many people died. Kuratowski, who knew Janiszewski well, writes in [3]:-

Janiszewski was an unusual personality, combining great creative talent, organisational talent, faith in the scholar's mission, ardent patriotism, a noble character and kind-heartedness. Receptive to ideas of progress and social justice, he underwent deep ideological changes. In his own words, he "was turning more and more to the left in politics" ...

Knaster tells us in [1] that Janiszewski:-

... donated for public education all the money he received for scientific prizes and an inheritance from his father. Before he died he willed his possessions for social works, his body for medical research, and his cranium for craniological study, desiring to be "useful after his death".

Dickstein wrote a commemorative address after Janiszewski's death. Although it repeats much of what we have already written about Janiszewski it is worth ending this biography by quoting part of the address (see for example [3]):-

Enthusiasm and strong will characterised Janiszewski not only in his scientific work, but in his life generally. His active participation in the Legions, his refusal to take an oath which was not compatible with his patriotic conscience, his work in the field of education, when at a most difficult time he entered that field as an enlightened and wise worker, free of any prejudice and partiality and ardently keen only to propagate light and truth - these facts prove that in the heart of a mathematicians seemingly detached from active life there glowed the purest emotions of affection and self-denial. If we also mention that, having very moderate needs himself, he dispensed all the means at his disposal to educate young talents, and that he bequeathed the property that he had inherited from his parents for educational purposes, and in particular for the education of outstanding individuals, then we may indeed exclaim from the bottom of our hearts that the memory of that life, devoted to the cause and interrupted so early, lives on in its results and deeds and will remain treasured and living for us, the witnesses of his work, and for generations to come.

1. B Knaster, Biography in Dictionary of Scientific Biography (New York 1970-1990).

http://www.encyclopedia.com/doc/1G2-2830902167.html

Books:

2. R Kaluza, The life of Stefan Banach (Boston, 1996).

3. K Kuratowski, Half a century of Polish mathematics (Warsaw, 1973).

Articles:

4. B Knaster, Zygmunt Janiszewski (on the 40th anniversary of his death) (Polish), Wiadomosci matematyczne (2) 4 (1960), 1-9.

5. K Kuratowski, Review of the Polish Academy of Sciences 4 (1959), 16-32.

6. Z Pawlikowska-Brozek, Zygmunt Janiszewski -organizer of science and author of the idea of the Polish mathematical school (Polish), Mathematics at the turn of the twentieth century (Katowice, 1992), 45-52.

|

|

|

|

تفوقت في الاختبار على الجميع.. فاكهة "خارقة" في عالم التغذية

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

أمين عام أوبك: النفط الخام والغاز الطبيعي "هبة من الله"

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

جرّاح عراقي: تقنيات مستشفى الكفيل مكّنتنا من إجراء عمليات انحراف العمود الفقري

|

|

|