Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension|

Read More

Date: 2024-04-01

Date: 2024-04-24

Date: 2024-03-15

|

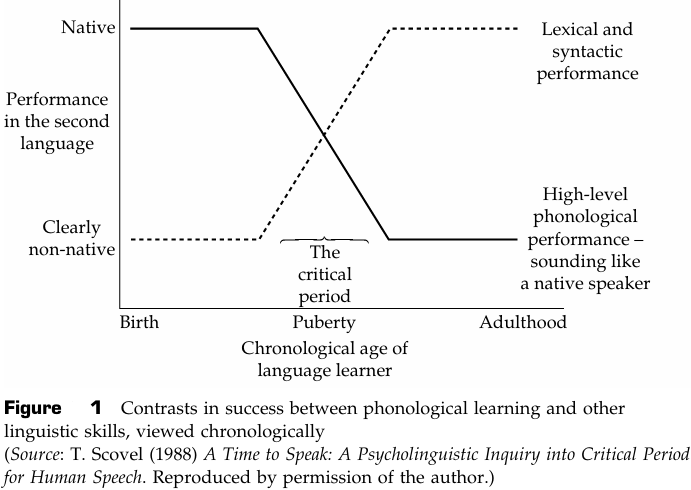

Mini Contrastive Analyses

Spanishh–Englis

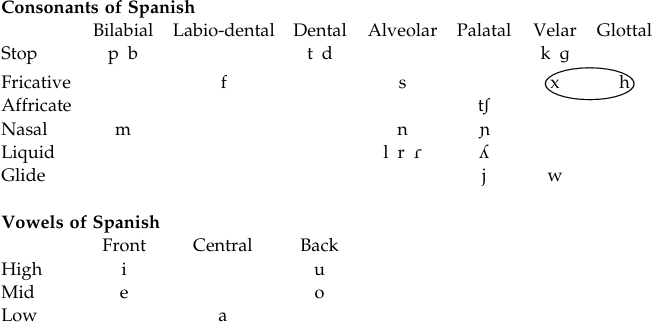

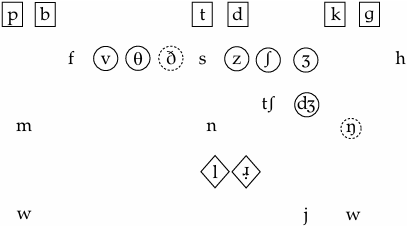

We start our description by giving the phonemic inventory of the L1 consonants and vowels.

Before we go into the mismatches, we should mention some facts about Spanish. While the status of the vowels is rather consistent across varieties of Spanish, consonants show considerable variation. For example, /θ/, which is not included in the above table, is used only in dialects in Spain. Voiceless velar and glottal fricatives are encircled to indicate that either one or the other, not both, occurs in a given variety. Also noteworthy is the fact that the palatal lateral liquid /ʎ/, which is in contrast with the alveolar lateral /l/ in some varieties, is gradually being lost.

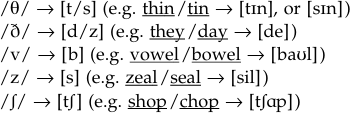

The inventory of the L1 (Spanish) given above is useful for depicting the target English phonemes that are missing. Accordingly, we can easily see that the targets /v, θ, ð, z, ʃ, ʒ, ʤ, ŋ/ will be problematic for learners, as Spanish does not have these phonemes (phonetically [ŋ] occurs in cinco, but in Spanish, unlike in English, it does not contrast with other phonemes). That these predictions are correct can be shown by the following frequently attested examples, where the missing targets are replaced by the closest sounds that are available in the native L1 inventory, resulting in several phonemic violations.

It should be mentioned that one of the target English sounds above, [ð], is different from the others; this sound is phonetically present in both languages but has different phonemic mappings. As mentioned earlier, it is a separate phoneme in English and contrasts with /d/ (e.g. they vs. day); in Spanish, however, [d] and [ð] are allophones of the same phoneme.

Although the inventory is capable of showing the above-mentioned problems, it is rather limited in scope, as different allophonic rules of identically described phonemes in two languages are also responsible for foreign accents. For example, despite the fact that the two languages in question have the same number of stop phonemes, these are far from being problem-free. Voiceless stops are always unaspirated in Spanish, whereas they are contextually (at the beginning of a stressed syllable) aspirated in English. Thus, in their production of English, Spanish speakers are expected to produce unaspirated stops in, for example, ton, pay, car. Also, voiced stops, /b, d, g/, of Spanish have fricative allophones, [ß, ð, ɣ] respectively. Stop variants occur after pauses, after nasals, and after /l/; the fricative variants occur in other environments. Thus, Spanish speakers may produce fricatives for target voiced stops in adore, aboard, and so on.

Distributional restrictions are also the cause of problems in L2 phonology. Spanish has rather severe restrictions with respect to final consonants. Since the language allows only /s, n, r, l/ (and maybe /d/) to occur in final position, we might encounter several instances of final consonant deletion because English can demand that all consonants (except /h/) occur in this position. Similarly, since the only nasal that can occur finally is /n/ in Spanish, a target such as from with a bilabial nasal may be realized with a final [n] instead.

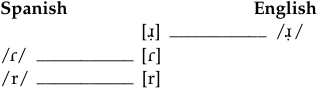

Another source of a foreign accent is salient phonetic dissimilarities in certain sounds between the two languages. This is nowhere more obvious than in a comparison of the liquids. While both Spanish and English have lateral and non-lateral liquids and can employ them in the same word positions, their clearly identifiable phonetic differences in the two languages produce easily detectable foreign accents. The alveolar lateral is always realized as ‘clear l’ (i.e. non-velarized) in Spanish, whereas the American English counterpart is produced mostly as shades of ‘dark l’ (i.e. velarized). The non-lateral liquids (i.e. r-sounds) of the two languages also exemplify considerable phonetic dissimilarity. The American English r is a retroflex approximant, while the two r-sounds of Spanish are a trill and a flap. Thus, we have the following mismatch:

We can summarize the above in the following overlay of the L1 inventory onto the target English inventory (Spanish phonemes that have no relevance to the mismatches, such as /ʎ, x, ɲ/, are not considered here):

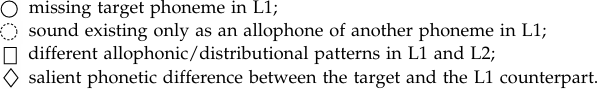

The following symbolizations are used throughout the comparisons between the target language (English) and the various first languages:

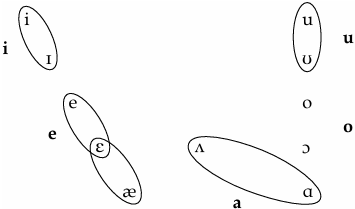

The comparison of the vowel systems also makes certain problematic aspects rather obvious. Although there are no distributional problems in vowels (i.e. Spanish vowels can occur in all word positions), Spanish has a far smaller number (five) of vowels than English, and this proves to be an important and frequent source of insufficient separation (i.e. under-differentiation) of target phonemic distinctions. The frequently attested lack of contrasts (i.e. homophonies) that results include /i/ – /ɪ/ (e.g. greed– grid), /u/ – /ʊ/ (e.g. fool– full), /Λ/ – /ɑ/ (e.g. buddy– body), /ε/ – /æ/ (e.g. mess– mass). The following chart summarizes these potential confusions:

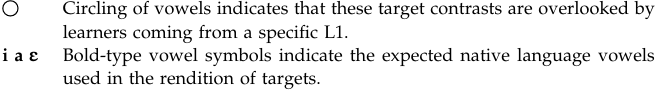

The following conventions are used throughout the comparisons with vowel systems of L1 and L2:

It should be pointed out that the use of identical phonetic symbols for the bold-type L1 vowel does not imply that it is phonetically identical to any of the L2 (English) targets. For example, we use /i/ and /ɪ/ for the English high front vowels. Spanish speakers’ rendition of /i/ does not mean that they are successful for English /i/ and unsuccessful for /ɪ/. Spanish substitution of /i/ is not identical to either English vowel. In almost all the languages we compare, the symbols /i, e, o, u/ indicate phonetically simple (not long and diphthongized) vowels. Similarly, the use of other symbols (e.g. /ε, ɔ/) does not make a claim that the phonetic qualities of these vowels are identical to those of English. The reader should keep these facts in mind when examining the vowel charts throughout.

The diphthongs are not expected to create problems for Spanish speakers as the language has a wide variety of diphthongs including all of those occurring in English.

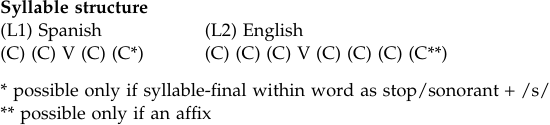

Phonotactics (i.e. sequential patterning) is another aspect to consider in the comparison. In the present case, we see that Spanish and English are rather disparate:

While English allows triple onsets and triple codas, the maximum number of consonants in Spanish in these positions is two. The number of consonants in clusters can tell only part of the whole story. The disparities are greater once we examine the other relevant dimension, namely the possible combinations. For example, English has a wide variety of double codas, whereas Spanish has very limited combinations (stop/sonorant + /s/) only in word-internal position. There are differences for the double onsets too. The variety of combinations Spanish allows is limited to stop//f/ + liquid; any English target cluster other than these (there is a multiplicity of cases) can create significant trouble for Spanish speakers learning English.

Finally, mention should be made of the suprasegmental effects. Firstly, we can mention the stress-timed (English) versus syllable-timed (Spanish) difference. A rather obvious consequence of this difference is seen in rhythm because of the lack of vowel reductions, which are mandatory in English. Another aspect of the prosodic differences is related to different stress patterns. Such mismatches are especially dangerous in the case of cognates. Learners may (and indeed do) fall into the ‘same/similar form and meaning’ trap between the two languages. This is especially true when Spanish words have the stress on the final syllable, which English avoids. Here are some examples of such conflicts:

• disyllabics: ult in Spanish vs. penult in English: color, labor, honor, fatal, accion/action;

• trisyllabics: ult in Spanish vs. antepenult in English: animal, general, cultural, natural;

ult in Spanish vs. penult in English: decision, informal, profesor/professor;

• four syllables: ult in Spanish vs. penult in English: artificial, horizontal, education/educacion;

ult in Spanish vs. antepenult in English: particular, original, opinion (or on pre-antepenult in English because the antepenult has an [@], which is unstressable: calculador/ calculator, operador/operator, navegador/navigator).

The following summarizes the major trouble spots:

• entirely missing targets: /v/ → [b], /θ/ → [t], /ð/ → [d], /ʃ/ → [tʃ], /z/ → [s];

• distribution: only /s, n, l, ɾ/ occur finally in L1;

• aspiration of target /p, t, k/;

• fricative variants of L1 voiced stops intervocalically (e.g. adore → [aðɔɾ]);

• significant phonetic violations: liquids;

• consonant clusters;

• insufficient separation of several target vowel contrasts;

• stress;

• rhythm.

|

|

|

|

4 أسباب تجعلك تضيف الزنجبيل إلى طعامك.. تعرف عليها

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

أكبر محطة للطاقة الكهرومائية في بريطانيا تستعد للانطلاق

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

العتبة العباسية المقدسة تبحث مع العتبة الحسينية المقدسة التنسيق المشترك لإقامة حفل تخرج طلبة الجامعات

|

|

|