Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension|

Read More

Date: 25-5-2022

Date: 27-5-2022

Date: 26-4-2022

|

Reflection: The development of the in English

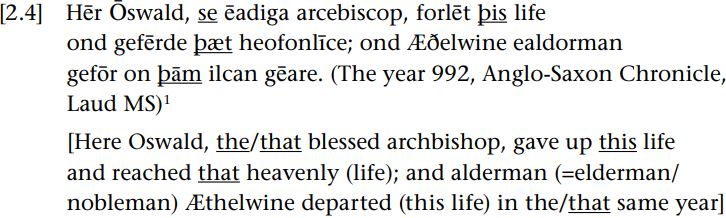

The earliest stages of English had no definite article, nor did it have a contrasting indefinite article. Speakers and writers in Old English (approximately 500 to 1100) deployed the demonstrative form se, from which the seems to have developed, for some of the functions undertaken by today’s the. Se is the nominative masculine form of the demonstrative and may not ring any present-day demonstrative bells, but the nominative and accusative neuter form is þæt (the first letter of this word represents the sound later represented by ) from which, as is plain to see, is derived the present-day demonstrative that (e.g. pass me that sandwich, please). Let us look at an example (demonstratives are underlined):

As one can see from the present-day translation, there are two points where the Old English demonstrative can be rendered by either present-day the or that. Both signal definiteness, that is, they invite participants to identify a particular entity (i.e. a particular archbishop; a particular year). Today, the difference between the and that in these contexts is that that, unlike the, is used to focus the target’s attention on something. But in Old English this use is not so clear. Incidentally, the other instance of that in “that heavenly (life)” is not the same. In this case, it involves a deictic contrast with the previous demonstrative, this, such that the referent moved from the relatively close state of “this life” to the relatively faraway state of “that heavenly life”. We will discuss deictic matters more fully, but the point to note here is that the Old English demonstrative se, along with its various forms, was deployed in a range of functions, including those for which we would regularly use the word the today.

Over time, then, a demonstrative form has developed into the definite article the English language has today. Note, with particular reference to Table 2.1, it has moved from the relatively contextual, extralinguistic category of deictic expressions to the relatively abstract, linguistic category of definite expressions; in other words, from more pragmatic to less. English is not alone in the way its definite article developed. Definite articles in Romance languages (e.g. French, Italian, Spanish), such as le, il, el, lo, la, have developed from the Latin demonstrative ille/illa (masculine/feminine), although there are complexities for specific dialects of these languages (cf. Klein-Andreu 1996).

Although the categories in Table 2.1 do not always represent continuous links in a chain, if a particular item develops functions outside its initial category, they are usually functions that belong to a less contextually-determined category – they rely less on a specific context for a particular meaning and instead have the “same” meaning for a range of contexts, that is they are more abstract (it is a matter of controversy as to whether this is true of all languages; see Frajzyngier 1996, for some counter evidence). Thus, not only are definite expressions often developed from deictic expressions, but anaphoric expressions are often developed from deictic expressions, and proper nouns sometimes develop into common nouns (hence, eponymic nouns, such as wellingtons, cardigan, sandwich, sadism and atlas). This movement is consistent with what has, in historical linguistics, been referred to as grammaticalisation:

As a lexical construction enters and continues along a grammaticalization pathway, it undergoes successive changes in meaning, broadly interpretable as representing a unidirectional movement away from its original or concrete reference and toward increasingly general and abstract reference. (Pagliuca 1994: ix)

Pagliuca’s statement makes the connection with a movement away from meanings anchored in a concrete context towards the abstract.

|

|

|

|

5 علامات تحذيرية قد تدل على "مشكل خطير" في الكبد

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

لحماية التراث الوطني.. العتبة العباسية تعلن عن ترميم أكثر من 200 وثيقة خلال عام 2024

|

|

|