Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension|

Read More

Date: 1-2-2023

Date: 19-1-2023

Date: 2023-08-18

|

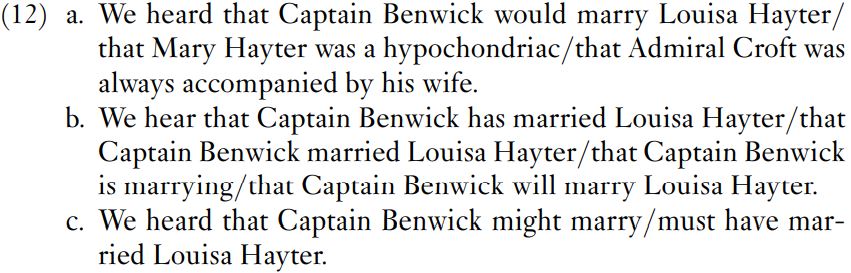

We turn now to other similarities and differences between main and subordinate clauses. The subordinate clauses in a given sentence are to a large extent grammatically independent of the main clause. They cannot stand on their own (in writing, at any rate), but the main clause does not control the choice of verb and other constituents, nor the choice of participant roles, tense, aspect and modal verbs. (The choices must make semantic sense, but that is a different question.) Compare the variants of the complement clause in (12).

In (12a), two of the complement clauses are active and the last one is passive. One complement clause is a copula construction, that Mary Hayter was a hypochondriac, while the other two are not. In (12b), one complement clause has a Perfect verb – has married, the second has a simple past tense – married, the third has a present-tense verb – is marrying, and the fourth has a future-tense verb – will marry. In (12c), the complement clauses have different modal verbs, might marry vs must (have) married.

In (12a), two of the complement clauses are active and the last one is passive. One complement clause is a copula construction, that Mary Hayter was a hypochondriac, while the other two are not. In (12b), one complement clause has a Perfect verb – has married, the second has a simple past tense – married, the third has a present-tense verb – is marrying, and the fourth has a future-tense verb – will marry. In (12c), the complement clauses have different modal verbs, might marry vs must (have) married.

Subordinate clauses are, however, subject to a number of constraints that do not apply to main clauses. For instance, main clauses can be declarative, interrogative or imperative, as shown in (13a–c).

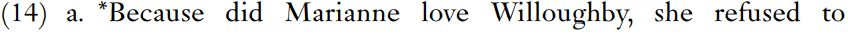

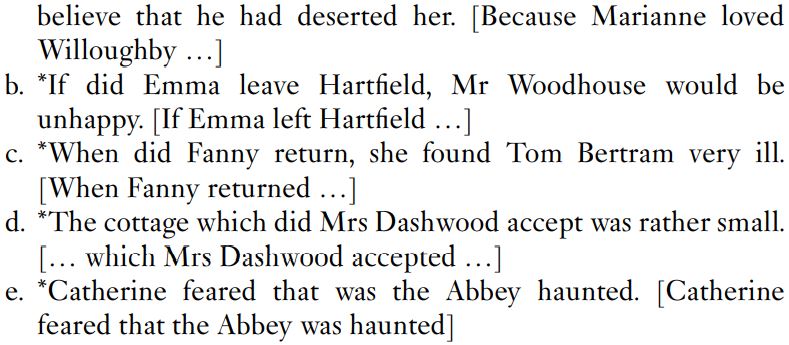

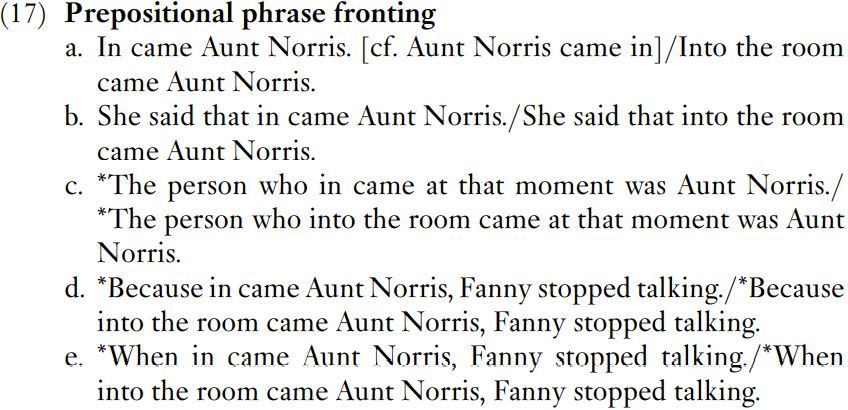

Subordinate clauses are not free with respect to choice of declarative, interrogative and imperative syntax. For example, relative clauses, adverbial clauses and most types of complement clause must have declarative syntax, as shown in (14).

The phrase ‘most types of complement clause’ was used because a number of verbs allow a type of complement that is traditionally called ‘indirect question’. Examples are given in (15).

The clauses introduced by whether/if and who are indirect questions. Example (15a) is completely declarative in syntax, apart from the WH word whether; (15b) is partly declarative and partly interrogative – declarative in the order of noun phrase and auxiliary verb (Mr Bennet had received) but interrogative in having the WH word who at the front of the clause. These subordinate clauses can be seen as corresponding to the main interrogative clauses Will Mr Bingley return to Netherfield? and Who did Mr Bennet receive in his library?

The clauses introduced by whether/if and who are indirect questions. Example (15a) is completely declarative in syntax, apart from the WH word whether; (15b) is partly declarative and partly interrogative – declarative in the order of noun phrase and auxiliary verb (Mr Bennet had received) but interrogative in having the WH word who at the front of the clause. These subordinate clauses can be seen as corresponding to the main interrogative clauses Will Mr Bingley return to Netherfield? and Who did Mr Bennet receive in his library?

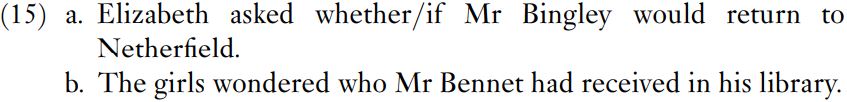

Interestingly, contemporary spoken English has the type of complement clause in (16). It is normal for spoken English in all sorts of formal and informal contexts and is beginning to turn up in written texts.

The complement clauses have straightforward interrogative syntax – was Alison coming to the party and who did you meet at the conference. These examples could be uttered with pauses between the clauses and with each clause having its own intonation pattern, but typically there is no pause and the whole utterance has one single intonation pattern. Note that although the complement clauses in (16) have interrogative syntax, they do not invalidate the statement that subordinate clauses are typically limited to declarative syntax.

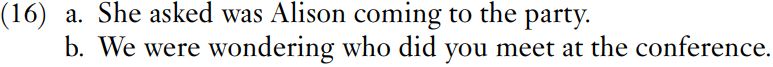

Subordinate clauses are limited in other respects. Main clauses, but not subordinate clauses, are open to a wide range of syntactic constructions. Consider the examples in (17).

The construction has a preposition in first position followed by the main verb followed by the subject NP. It can occur in declarative main clauses, and in complement clauses – compare (17b) – but not in relative clauses or adverbial clauses.

The construction has a preposition in first position followed by the main verb followed by the subject NP. It can occur in declarative main clauses, and in complement clauses – compare (17b) – but not in relative clauses or adverbial clauses.

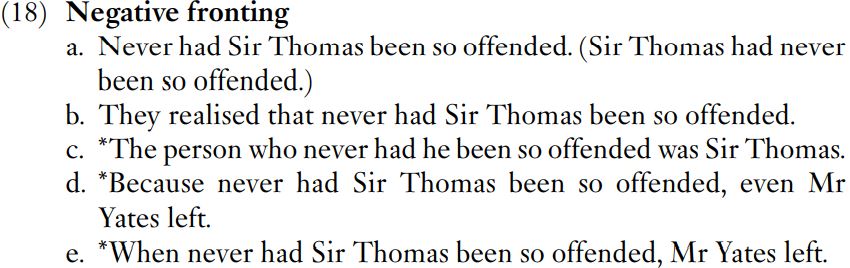

Example (18b) can be derived from Sir Thomas had never been so offended. Never moves to the front of the clause and Sir Thomas and had change places. As with preposition fronting, the construction is acceptable in main clauses and complement clauses but not in relative or adverbial clauses.

Didn’t he? in (19a) is a tag question, so named because the structure consists of a declarative clause, Dr Grantly habitually ate too much rich food, with a question tagged on at the end, didn’t he? Tag questions consist of verbs such as did, might, can and so on plus a pronoun, and possibly with the negation marker -n’t or not.

Didn’t he? in (19a) is a tag question, so named because the structure consists of a declarative clause, Dr Grantly habitually ate too much rich food, with a question tagged on at the end, didn’t he? Tag questions consist of verbs such as did, might, can and so on plus a pronoun, and possibly with the negation marker -n’t or not.

Tag questions do not occur in any subordinate clause. Note that in an example such as Edmund knew that Dr Grantly died of apoplexy, didn’t he?, the tag question relates to the verb in the main clause, knew, and not to died of apoplexy. Note also that the examples in (19) are intended to be taken as written language and that spoken utterances must be supposed to carry a single intonation pattern and to have no breaks. The latter stipulation is necessary, because speakers do produce utterances such as because Dr Grantly ate too much rich food, break off the utterance and ask the tag question, and then, having received an answer, go back to the main clause. That type of interrupted syntax is not relevant for present purposes.

The data in (14)–(19) suggest that there is a hierarchy of subordination. Complement clauses are the least subordinate and allow preposition fronting, negative fronting and, depending on the head verb, interrogative structures. Relative clauses and adverbial clauses are most subordinate. They exclude all the constructions in (14)–(19), together with interrogative and imperative structures.

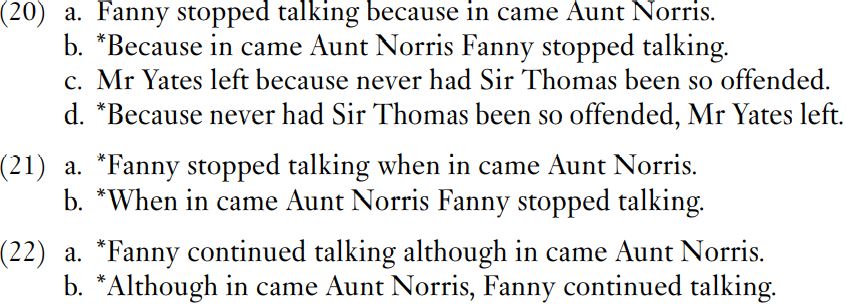

The position of some adverbial clauses on the hierarchy is not straightforward but is affected by their position in sentences. As (7) shows, adverbial clauses of reason can precede or follow the main clause. When they follow the main clause, they allow negative fronting and preposition fronting, but not when they precede it. This suggests that in the latter position they are more subordinate. Consider the examples in (20), and note the examples in (21) and (22) which show that adverbial clauses of time and concession do not behave this way.

Adverbial clauses of reason following the main clause seem to play a different role from the one they play preceding the main clause. It has been suggested that adverbial clauses preceding the main clause serve as signposts to the text, whereas adverbial clauses following the main clause serve as comments on what has been said or written. In conversation, adverbial clauses may (emphasis on may) be separated from the main clause by a pause and may have their own intonation pattern, though clearly these considerations are irrelevant to written text.

Adverbial clauses of reason following the main clause seem to play a different role from the one they play preceding the main clause. It has been suggested that adverbial clauses preceding the main clause serve as signposts to the text, whereas adverbial clauses following the main clause serve as comments on what has been said or written. In conversation, adverbial clauses may (emphasis on may) be separated from the main clause by a pause and may have their own intonation pattern, though clearly these considerations are irrelevant to written text.

It has been proposed that sequences of main clause + adverbial clause of reason come close to being conjoined clauses, that is, clauses of equal status. This proposal seems on the right lines, and it opens an interesting view of when clauses that have been (mistakenly) regarded as subordinate. Compare (21a), reproduced as (23a), and (23b).

Example (23a) presents two events as simultaneous: Fanny stopped talking and Aunt Norris came in. Example (23b) presents one event as following the other: Fanny stopped talking, after which Aunt Norris came in. It is not entirely clear why (23b) is acceptable, but it is worth pointing out that when can be replaced by and then, that is, by an expression that overtly conjoins the two clauses and fits with the notion of main clause + adverbial clause as two conjoined clauses. Example (23a) does not allow the substitution, since the two events are presented as simultaneous

|

|

|

|

تفوقت في الاختبار على الجميع.. فاكهة "خارقة" في عالم التغذية

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

أمين عام أوبك: النفط الخام والغاز الطبيعي "هبة من الله"

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

قسم شؤون المعارف ينظم دورة عن آليات عمل الفهارس الفنية للموسوعات والكتب لملاكاته

|

|

|