Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension|

Read More

Date: 2025-04-19

Date: 2024-01-23

Date: 2024-01-23

|

Scale structure and standard of comparison

Our analysis builds on the same core hypothesis that underlies the Dowty/Abusch analysis: the variable aspectual properties of DAs derive from the semantic properties of the adjectival part of their (decomposed) lexical meanings. However, we begin from different assumptions about how to capture the semantics of gradability and vagueness. Whereas Abusch’s analysis is built on a semantics of gradable predicates in which they denote (contextdependent) properties of individuals, we start from the assumption that such expressions do not themselves express properties, but rather encode measure functions: functions that associate objects with ordered values on a scale, or degrees.1

In particular, we follow Bartsch and Vennemann (1972, 1973) and Kennedy (1999b) and assume that gradable adjectives in English directly lexicalize measure functions.2 We further assume following Hay et al. (1999) (cf. Pinon2005) hat such measure functions can be relativized to times (an object can have different degrees of height, weight, temperature, etc. at different times), so that the adjective cool, for example, denotes a function cool from objects x and times t that returns the temperature of x at t. A consequence of this analysis is that a gradable adjective by itself does not denote a property of individuals, but must instead be converted into one so that composition with its individual argument results in a proposition; this is the role of degree morphology: comparative morphemes, sufficiency/excess morphemes, intensifiers, and so forth.

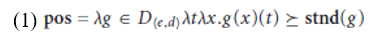

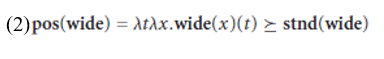

Among the set of degree morphemes is a null degree head (or possibly a semantically equivalent type-shifting rule) that is involved in the interpretation of the so-called positive (morphologically unmarked) form, which denotes the function pos in (1).3

Here stnd is a function from gradable adjective meanings to degrees that returns a standard of comparison for the adjective in the context of utterance: the minimum degree required to “stand out” in the context relative to the kind of measurement expressed by the adjective (Kennedy 2007; Bogusławski 1975; Fara 2000; cf. Bartsch and Vennemann 1972, 1973; Cresswell 1977; von Stechow 1984). The positive form of wide, for example, denotes the property in (2), which is true of an object (at a time) just in case its width exceeds the standard, that is, just in case it stands out in the context of utterance relative to the kind of measurement represented by the measure function wide (“linear extent in a horizontal direction perpendicular to the perspective of reference, or something like that).

The truth of a predication involving the positive form of a gradable adjective thus depends on two factors: the degree to which it manifests the gradable property measured by the adjective (in this case, its width), and the actual value of the standard of comparison in the context (here the degree returned by stnd(wide)). The latter value is a function both of (possibly variable) features of the conventional meaning of the adjective (such as its domain, which may be contextually or explicitly restricted to a particular comparison class; see Klein 1980; Kennedy 2007), and of features of the context (such as the domain of discourse, the interests/expectations of the participants in the discourse, and so forth).

However, there is an asymmetry in the relative contributions of conventional (lexical) and contextual information to the determination of the standard of comparison. Rotstein and Winter (2004), Kennedy and McNally (2005), and Kennedy (2007) provide extensive empirical arguments that when an adjective uses a closed scale (a feature of its conventional meaning), the standard of comparison invariably corresponds to an endpoint of the scale: the minimum in some cases (bent, open, impure, etc.) and the maximum in others (straight, closed, pure, etc.). In other words, the standards of comparison of closed scale adjectives are not context-dependent.

Kennedy (2007) argues that this distinction follows from the semantics of the positive form: specifically from the fact that the standard represents the minimum degree required to stand out relative to the kind of measure encoded by the adjective. The difference between adjectives that use closed measurement scales and those that use open ones is that the former come with “natural transitions”: the transition from a zero to a non-zero degree on the scale (from not having any degree of the measured property to having some of it) in the case of an adjective with a lower closed scale, or the transition from a non-maximal to a maximal degree (from having an arbitrary degree of the measured property to having a maximal degree of it) in the case of an adjective with an upper closed scale. Kennedy proposes that what it means to stand out” relative to a property measured by a closed scale adjective is to be on the upper end of one of these transitions. In the case of adjectives with lower closed scales like wet, impure, and so forth, this means having a non-zero degree of the measured property; in the case of adjectives with upper closed scales like dry and pure, this means having a maximal degree of the measured property.4

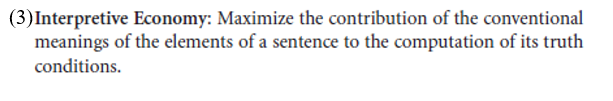

Scale structure explains why the endpoints of closed scale adjectives are potential standards (only closed scale adjectives have scales with endpoints), but it does not explain why they are the actual standards. There is nothing inherently incompatible between a closed scale and a context-dependent, non endpoint- oriented standard, so the fact that closed scale adjectives default to endpoint-oriented standards must follow from some other constraint. According to Kennedy, this constraint is the principle of Interpretive Economy stated in (3).

The effect of Interpretive Economy is to make a contextual standard a “last resort”: since the natural transitions provided by the endpoints of a closed scale provide a basis for fixing the standard of comparison strictly on the basis of the conventional (lexical) meaning of a closed scale adjective, they should always be favored over a context-dependent standard. In contrast, nothing inherent to the meaning of an open scale adjective beyond its dimension of measurement (e.g. width vs. depth) provides a basis for fixing the standard. This means that contextual factors such as the domain of discourse, the interests and expectations of the discourse participants, and so forth must be taken into consideration when determining how much of the measured property is enough to stand out, resulting in the familiar context dependent, vague positive form interpretations of adjectives like wide and deep.

1 Following Kennedy and McNally (2005), we take scales to be triples _S, R, ‰_ where S is a set of degrees, R an ordering on S, and ‰ a value that represents the dimension of measurement. Scales may vary along any of these parameters: the structure of S (e.g., whether it is open or closed), the ordering relation (≺ for increasing, “positive” adjectives like warm; _ for decreasing, “negative” adjectives like cool), and the dimension (temperature, width, depth, linear extent, temporal extent, etc.). Semantic differences between gradable adjectives are primarily based on differences in the kinds of scales they use.

2 An alternative (and more common) analysis of gradable adjectives is one in which they do not directly denote measure functions, but incorporate them as part of their meanings (see e.g. Cresswell 1977; von Stechow 1984; Heim 1985, 2000; Klein 1991). On this view, a gradable adjective like cool expresses the relation between degrees and individuals in (i), where cool is a measure function.

(i) [[[A cool ]]] = ÎdÎx.cool(x) _ d

Our proposals in this chapter can be made consistent with this analysis of gradable adjectives by simply assuming that measure functions correspond not directly to adjective denotations, but rather to more basic units of meaning, which are part of the lexical semantic representations of both gradable adjectives and verbs of gradual change.

3 At the risk of confusion, we follow descriptive tradition and use “positive form” to refer to the morphologically unmarked use of a predicative or attributive adjective. This sense of “positive” is distinct from the one used to refer to adjectival polarity, e.g. the characterization of warm as a (polar) positive adjective and cool as a (polar) negative one.

4 Adjectives with totally closed scales are somewhat more complicated: some can have either maximum or minimum standards (e.g. opaque), which is expected given the considerations articulated above, but others have only maximum standards (e.g. full). See Kennedy (2007) for discussion.

|

|

|

|

تحذير من "عادة" خلال تنظيف اللسان.. خطيرة على القلب

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

دراسة علمية تحذر من علاقات حب "اصطناعية" ؟!

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

العتبة العباسية المقدسة تحذّر من خطورة الحرب الثقافية والأخلاقية التي تستهدف المجتمع الإسلاميّ

|

|

|