Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension|

Read More

Date: 25-2-2022

Date: 2024-01-10

Date: 10-1-2022

|

Aspectual composition with degrees Introduction

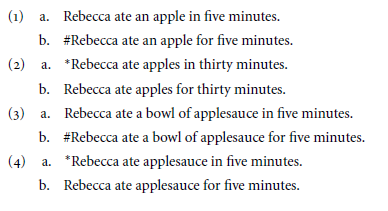

Approaches to aspectual composition (most notably Krifka 1989, 1992; Verkuyl 1993) have generally focused on how to account for contrasts such as those in (1) and (2), where compatibility with a temporal in-adverbial is taken to indicate a telic interpretation, and compatibility with a temporal for-adverbial to signal an atelic interpretation, of the phrase that the adverbial attaches to. Nothing hinges on the use of the terms telic and atelic here, and for present purposes, bounded and unbounded would do equally well.

Although the prevailing view has been that sentences such as those in (1b) and (3b) are unacceptable, it is also clear that the corresponding sentences in (2a) and (4a) are less acceptable by comparison. The present view, in agreement with Smollett (2005), is that the sentences in (1b) and (3b) are acceptable but require more contextual support than the corresponding ones in (1a) and (3a). Thus, out of the blue (1a) requires no special effort, whereas acceptance of (1b) might lead one to imagine that Rebecca is a small child who hardly ever finishes the apples she is given to eat.1 In contrast, the sentences in (2a) and (4a) are considered to be unacceptable.

One task of an aspectual theory is to determine the content of terms such as telic and atelic. In Krifka’s (1989, 1992) approach, a VP is telic if the corresponding event predicate is quantized, whereas it is atelic if the corresponding event predicate is cumulative:

In these definitions, P is a one-place predicate of events or ordinary individuals (thus a, b stand for events or ordinary individuals), _ denotes the proper part relation, and ⊕ designates the sum operation. In prose, P is quantized just in case it never applies both to an event or an individual and to a proper part of that event or individual, P is non-unique only if it applies to at least two events or individuals, and P is cumulative just in case it is non-unique and applies to the sum of two events or individuals whenever it applies to each of the two events or individuals independently. Observe that quantization and cumulativity form contraries, hence if P is quantized, it is not cumulative, but P may be neither quantized nor cumulative. Moreover, if P is not quantized, then it is non-unique.2

To illustrate how quantization and cumulativity are applied, consider the examples in (1) and (2). In general, tense will be ignored, because it is not crucially relevant to the issues discussed in this chapter. The telic VP eat an apple in (1a) is taken to denote the set of (minimal) events in which an apple is (completely) eaten. Since no such event in which an apple is eaten properly contains an event in which an apple is eaten, the denotation of this VP is quantized (therefore not cumulative). In contrast, the atelic VP eat apples in (2b) is assumed to denote the set of events in which one or more apples are eaten. Since the sum of any two events in which one or more apples are eaten is also an event in which one or more apples are eaten, the denotation of this VP is cumulative (hence not quantized), assuming that it is non-unique. The reasoning is analogous for the telic VP eat a bowl of applesauce in (3a) (quantized) versus the atelic VP eat applesauce in (4b) (cumulative). According to this line of thinking, the atelic interpretation of eat an apple in (1b) should be cumulative, which would be the case if the VP on this reading denoted the set of events in which a specific apple is partly eaten.3 This would hold because the sum of two events in which a specific apple is partly eaten is again an event in which that apple is partly eaten: since a specific apple is at issue, it is kept constant.4

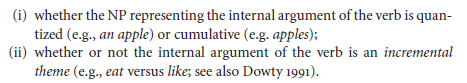

Beyond characterizing sentences such as those in (1)–(4) in terms of telicity and atelicity and clarifying that these two notions correspond to quantization and cumulativity, respectively, another task of an aspectual theory is to show how these results are achieved compositionally. For example, how does the telicity of eat an apple follow from the meaning of eat and that of an apple? The same may be asked about the atelicity of eat apples. Moreover, why does eat apples not allow for a telic reading, whereas eat an apple does allow for an atelic reading? In Krifka’s approach, these results – again, with the exception of examples such as (1b) and (3b), which are considered to be unacceptable – depend on essentially two factors:

The factor mentioned in (i) is reasonably straightforward, once given the definitions of quantization and cumulativity and an appropriate analysis of the NPs in question. In contrast, the criterion described in (ii), namely, the characterization of an incremental theme, is somewhat involved and is formulated in terms of certain properties of thematic relations, where a thematic relation is treated as a two-place relation between ordinary individuals and events. The three central properties of incremental themes for Krifka are uniqueness of objects, mapping to objects, and mapping to events. Without diving into the formal details, uniqueness of objects states that if x is an incremental theme of e, then x is the unique incremental theme of e. Mapping to objects says that if x is an incremental theme of e, then every subevent e of e has a part x of x as its own incremental theme. Conversely, mapping to events states that if x is an incremental theme of e, then every part x of x is an incremental theme of a subevent e of e. These three properties specify the core of what it means for a thematic relation to be an incremental theme.5 Assuming this setup and excluding an iterative interpretation, it can be shown that a VP is telic (or its corresponding event predicate is quantized) if the verb takes an incremental theme and the NP corresponding to the incremental theme is quantized, as in (1a) and (3a). Furthermore, a VP is atelic (or its corresponding event predicate is cumulative) if the verb takes an incremental theme and the NP corresponding to the incremental theme is cumulative, as in (2b) and (4b).6

Another aspectual problem, first succinctly described by Dowty1979 and then freshly addressed by Hay, Kennedy and Levin (1999) and Kennedy and Levin (2002), is posed by degree achievements:7

For Dowty, the problem posed by these examples was how to treat vagueness and gradual change with his sharp and instantaneous become predicate, a puzzle that he never really managed to solve. Hay et al. and Kennedy and Levin, equipped with an analysis of gradable adjectives (that Dowty lacked), propose a treatment of degree achievements that aims to do justice to their deadjectival character and to account for their telic uses as well.8

Although the account that Hay et al. and Kennedy and Levin propose will be discussed in detail later on, their idea is that degree achievements have a “degree of change” argument d that measures a change in the extent to which an individual has a certain gradable property. Depending how d is specified, the resulting VP is either atelic or telic. For instance, in (8b) there is an unspecified degree of change in the extent to which the soup becomes cool (this corresponds to the existential binding of d), which yields an atelic (cumulative) interpretation, whereas in (9b) the degree of change in the extent to which the soup becomes cool is contextually determined (e.g., the value of d is large enough so that the soup becomes cool enough to eat without the risk of burning one’s mouth), which results in a telic (quantized) interpretation.

At first glance, there does not appear to be so much in common between the data in (1)–(4) and those in (8)–(9). More strikingly, perhaps, there seems to be even less in common between Krifka’s account and the one proposed by Hay et al. and Kennedy and Levin. Nevertheless, Hay et al. and Kennedy and Levin claim that their degree-based account can be naturally extended to deal with data such as those in (1)–(4) and that it can even do so without the mapping properties that Krifka appeals to in order to characterize incremental themes. As Kennedy and Levin (2002: 2, 12) put it, “In our analysis, quantization/ telicity follows completely from the structure of the degree of change argument” and “Telicity is determined solely by the semantic properties of the degree of change.”

Viewing the matter more broadly, the advantage of a unified degree-based account of aspectual composition would not merely reside in providing a common framework for the treatment of data such as those in (1)–(4) and (8)–(9), but it would also serve to capture more explicitly the intuition that verbs with an incremental theme are gradable. This intuition is present in Krifka’s analysis, but it is expressed in a way that tends to conceal rather than to reveal how this sort of gradability is related to gradability in the adjectival domain. Furthermore, an advantage of having an explicit representation of degrees is that it would make it easier to talk about the degree to which an event type is realized, something that is tricky to formulate in Krifka’s approach without introducing degrees in the first place.9

In addition to degree achievements and verbs with an incremental theme, degrees have other potential applications in the verbal domain. To mention several, Kiparsky (2005) argues that the choice of structural case in Finnish (Accusative versus Partitive) depends on the gradability of the verbal predicate. Tamm (2004) proposes that the choice between Total and Partitive case in Estonian is also sensitive to the gradability of the verbal predicate (though Estonian and Finnish differ in certain details). Martin (2006: chap. 8.2) considers the possibility of treating the intriguing difference between French convaincre ‘convince’ and persuader ‘persuade’ in terms of gradability. In previous work (Pinon 2000, 2005), I appealed to degrees to account for gradually and adverbs of completion (see also Kennedy and McNally 1999 for the latter). Finally, it should be acknowledged that the idea of using degrees to analyze verbs of gradual change in a formal semantics goes back at least to Ballweg and Frosch (1979). Interestingly, Ballweg and Frosch were shy about having degrees represented in their logical language, yet they had them in their model, albeit qua equivalence classes of individuals.

1 Observe that judgments improve if the object NP is definite:

(i) Rebecca ate the apple for five minutes (before dropping it on the floor).

(ii) Rebecca ate her apple for five minutes (before dropping it on the floor).

(ii), in particular, seems unobjectionable. Arguably, the difficulty in (1b) and (3b) is that we need a

specific apple or bowl of applesauce that is repeatedly partially affected, and yet an existential reading of the object NP does not (automatically) yield this. Once a specific reading is forced (cf. a certain apple), the judgments pattern more readily like those of (i) and (ii).

2 The definition of cumulativity in (7) is not quite equivalent to either the notion of cumulativity or that of strict cumulativity in Krifka (1989, 1992). The present definition of cumulativity, which appeals to non-uniqueness, ensures that quantization and cumulativity form contraries, even if the denotation of P is empty.

3 Since Krifka’s approach takes sentences such as those in (1b) and (3b) to be unacceptable, this extension is mine.

4 See note 1 in this connection. For the paraphrase to work, partly should be understood in the sense of improper part, thus a partial eating of an apple is compatible with a complete eating of it. Observe also that if an apple were interpreted existentially, the VP would not be cumulative, even if it meant “partly eat an apple,” because in this case the choice of apple might well vary between the two events initially selected.

5 The incremental theme of verbs of consumption (eat) and creation (write) additionally satisfy uniqueness of events, which states that if x is an incremental theme of e, then x is an incremental theme of no other event but e.

6 This is a fairly high-level summary of Krifka’s account – see Krifka (1989, 1992) for the details.

7 The term “degree achievement” is due to Dowty. It is retained for the sake of tradition, but note that degree achievements are actually a kind of accomplishments and not achievements.

8 Kennedy and Levin distinguish verbs of directed motion (sink, ascend) from degree achievements (lengthen, cool), whereas Dowty, as far as I can tell, would regard them all as degree achievements. For present purposes, I take verbs of directed motion to be a species of degree achievements and do not discuss them as a separate class, though they could certainly receive separate attention in a more elaborate treatment.

9 In Pinon (2000, 2005), my strategy was to show how degrees could be introduced in a Krifkastyle analysis without assuming that verbs with an incremental theme have a degree argument to begin with. Although I still think that there is merit in this strategy, the approach that I propose takes such verbs to have a degree argument from the outset, in agreement with Kennedy and Levin in this respect (though the details differ).

|

|

|

|

تحذير من "عادة" خلال تنظيف اللسان.. خطيرة على القلب

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

دراسة علمية تحذر من علاقات حب "اصطناعية" ؟!

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

العتبة العباسية المقدسة تحذّر من خطورة الحرب الثقافية والأخلاقية التي تستهدف المجتمع الإسلاميّ

|

|

|