النبات

النبات

الحيوان

الحيوان

الأحياء المجهرية

الأحياء المجهرية

علم الأمراض

علم الأمراض

التقانة الإحيائية

التقانة الإحيائية

التقنية الحيوية المكروبية

التقنية الحيوية المكروبية

التقنية الحياتية النانوية

التقنية الحياتية النانوية

علم الأجنة

علم الأجنة

الأحياء الجزيئي

الأحياء الجزيئي

علم وظائف الأعضاء

علم وظائف الأعضاء

الغدد

الغدد

المضادات الحيوية

المضادات الحيوية|

Read More

Date: 12-10-2015

Date: 21-10-2015

Date: 20-10-2015

|

Male Reproductive System

Reproduction is essential for any species to sustain its population. In the simplest sense, the most important function of every living organism is reproduction. Organs of the male and female reproductive systems play a central role in sexual reproduction by creating, nourishing, and housing sex cells called gametes.

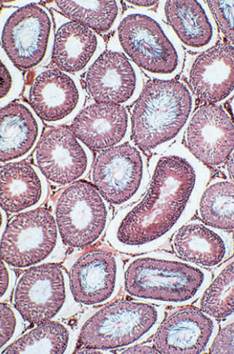

The human male reproductive system consists of gonads called testes, a series of ducts (epididymis, vas deferens, ejaculatory duct, urethra) that serve to transport spermatozoa to the female reproductive tract, and accessory sex glands (seminal vesicles, prostate, and bulbourethral glands).

Testes

The testes (singular, testis) are paired structures that originally develop in the abdomen and descend into the scrotum, a sac of skin and connective tissue positioned outside the pelvic cavity. This scrotal location is important for maintaining a testicular temperature, approximately 1.5 to 2.5 degrees Celsius (34.7 to 36.5 degrees Fahrenheit) below body temperature, required for spermatogenesis (sperm production). Testes also serve important endocrine functions as the source of male sex steroids called androgens. The most abundant androgen is testosterone.

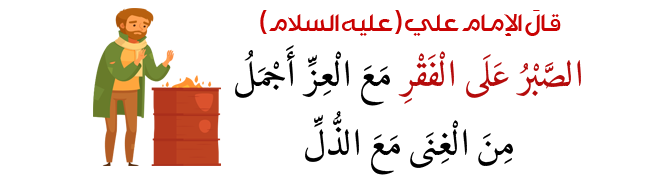

Inside each testis is a network of fine-diameter tubes called seminiferous tubules. Sertoli cells form the walls of a seminiferous tubule. Sertoli cells nourish, support, and protect developing germ cells, which undergo cell division by meiosis to form spermatozoa (immature sperm). During spermatogenesis, germ cells begin near the wall of a seminiferous tubule, and after division they are shed into the tubule. Proteins produced by Sertoli cells are required for spermatogenesis, as is testosterone.

Hormonal Control

Surrounding the tubules are clusters of interstitial cells, which synthesize testosterone and secrete it into the bloodstream. Testosterone is present in infant boys, although synthesis increases dramatically at puberty around age thirteen. This increase stimulates the onset of spermatogenesis and development of accessory sex glands. All male reproductive organs require testosterone for functions such as protein synthesis, fluid secretion, cell growth, and cell division. Androgens also play important roles in the male sexual response and stimulate secondary sex characteristics such as skeletal development, facial hair growth, deepening of the voice, increased metabolism, and enlargement of the testes, scrotum, and penis.

A photomicrograph of human testis showing spermatogenesis

Sperm production and androgen synthesis are controlled by a complex feedback loop involving the testes, hypothalamus, and pituitary gland. The pituitary controls testis function by producing follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH). FSH stimulates spermatogenesis, in part by affecting Sertoli cells, while LH stimulates androgen production by interstitial cells. Pituitary production of these hormones depends on secretion of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) by the hypothalamus. Elevated levels of GnRH initiate puberty.

How does this feedback loop prevent testosterone levels from getting too high or too low? While some may joke that the testis controls the brain in boys, there is some truth to this statement: the testis can control brain function. The production of LH is controlled by the actions of testosterone on the hypothalamus and pituitary. If testosterone concentration is elevated, testosterone inhibits production of GnRH by the hypothalamus; subsequently, LH and FSH production decreases.

Sperm Maturation

Spermatozoa leave each testis through small tubes called efferent ductules. Fluid pressure from secretions in the testis and ciliated cells in the efferent ductules help move spermatozoa into the epididymis. Testicular spermatozoa are immature because they cannot swim and lack the ability to penetrate an egg.

Sperm maturation occurs in the epididymis. Located adjacent to the testis, the epididymis contains a single, highly coiled tubule nearly 6 meters (19.6 feet) long. Sperm transport through the epididymis takes approximately twenty days. As sperm transit the epididymis, they are bathed in a specialized fluid rich in proteins, ions, and a number of other molecules. Complex interactions between spermatozoa and epididymal fluid contribute to sperm maturation. The epididymis is also a site for sperm storage and for the protection of sperm against chemical injury.

The male reproductive system provides for the formation, maturation, storage, and ejaculation of sperm. Both sperm and urine exit through the urethra.

Sperm Formation and Ejaculation

From the epididymis, spermatozoa enter a muscular tube called the vas deferens (approximately 45 centimeters [17.7 inches] long). The vas deferens contracts during the release of sperm—a process called ejaculation—to move spermatozoa out of the epididymis and into the ejaculatory duct, where sperm are mixed with secretions from the seminal vesicles. The ejaculatory duct enters the urethra as it passes through the prostate gland. In males, the urethra serves a dual purpose transporting sperm to the penis and urine from the urinary bladder.

The accessory sex glands consist of a single prostate gland and paired seminal vesicles and bulbourethral glands. The prostate and seminal vesicles secrete seminal fluid, or semen, a viscous mixture of spermatozoa and fluid from accessory sex glands. Spermatozoa constitute 10 percent of semen volume and number approximately 50 to 150 million sperm per milliliter. Combined secretions from the seminal vesicles and prostate account for roughly 90 percent of semen volume. The seminal vesicle secretions are rich in fructose (which serves as an energy source for spermatozoa), prostaglandins, and proteins that facilitate clotting of ejaculated semen in the female.

Prostate secretions are rich in zinc, citric acid, antibiotic like molecules, and enzymes important for sperm function. A protein called prostate- specific antigen can show elevated levels in the blood under conditions such as prostate growth. During sexual excitation, the bulbourethral glands produce a droplet of alkaline fluid that neutralizes residual urine in the urethra, protecting the sperm from its acidity.

Anatomy of the human sperm.

The penis contains two bodies of tissue (corpora cavernosa) above the urethra and a lower cylinder of tissue (corpus spongiosum) surrounding the urethra. The enlarged tip of the penis is called the glans penis. Mechanisms responsible for penile erection are complex. During sexual arousal, penile arteries dilate and a large volume of blood fills the penis, resulting in erection. The nervous system plays an important role in controlling erection and ejaculation.

The parasympathetic division of the autonomic nervous system regulates erection, whereas ejaculation is triggered by sympathetic impulses. Medical and emotional conditions can cause clinical disorders of erectile dysfunction. Drugs such as Viagra increase erectile function by improving blood flow into penile tissue. Many factors result in poor fertility or infertility in males including hormone imbalances, reproductive tract blockages, decreased sperm concentration, and abnormal sperm.

The journey of spermatozoa from formation to release is complicated. Reproduction of any individual is never guaranteed, yet through combined functions of male and female reproductive organs, nature has provided a sophisticated sequence of biological events designed to maximize the likelihood that we pass our genes to future generations.

References

Goldstein, Irwin. “Male Sexual Circuitry.” Scientific American (2000): 70-75.

Marieb, Elaine N. Human Anatomy and Physiology, 5th ed. Menlo Park, CA: Benjamin Cummings, 2000.

Robaire, Bernard, John L. Pryor, and Jacquetta M. Trasler, eds. Handbook of Andrology. San Francisco, CA: American Society of Andrology, 1998. Also available at <http://www.andrologysociety.com/resources.book.cfm>

|

|

|

|

تفوقت في الاختبار على الجميع.. فاكهة "خارقة" في عالم التغذية

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

أمين عام أوبك: النفط الخام والغاز الطبيعي "هبة من الله"

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

خدمات متعددة يقدمها قسم الشؤون الخدمية للزائرين

|

|

|