Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension|

Read More

Date: 2023-11-22

Date: 2023-11-24

Date: 4-2-2022

|

In traditional grammars, finite auxiliaries are said to agree with their subjects. Since (within the framework used here) finite auxiliaries occupy the head T position of TP and their subjects are in spec-TP, in earlier work agreement was said to involve a specifier–head relationship (between T and its specifier). However, there are both theoretical and empirical reasons for doubting that agreement involves a spec–head relation. From a theoretical perspective, Minimalist considerations lead us to the conclusion that we should restrict the range of syntactic relations used in linguistic description, perhaps limiting it to the relation c-command created by merger. From a descriptive perspective, a spec– head account of agreement is problematic in that it fails to account for agreement between the auxiliary are and the nominal several prizes in passive structures such as:

Since the auxiliary are occupies the head T position of TP in (1) and the expletive pronoun there is in spec-TP, a spec–head account of agreement would lead us to expect that are should agree with there. But instead, are agrees with the in situ complement several prizes of the passive participle awarded. What is going on here? In order to try and understand this, let’s take a closer look at the derivation of (1).

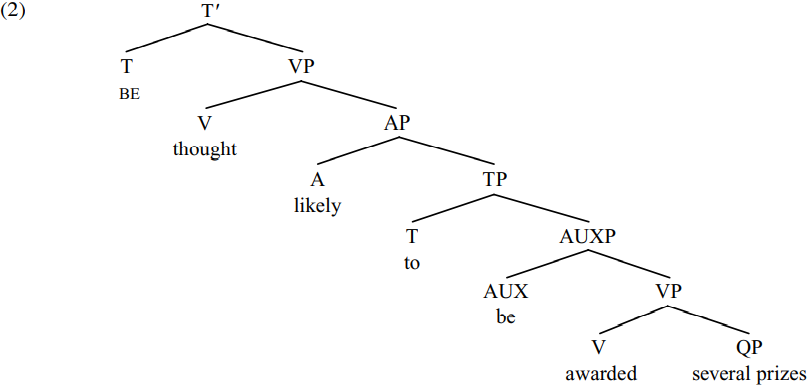

The quantifier several merges with the noun prizes to form the QP several prizes. This is merged as the thematic complement of the passive verb awarded to form the VP awarded several prizes. This in turn is merged with the passive auxiliary be to form the AUXP be awarded several prizes. This is then merged with the infinitival tense particle to, forming the TP to be awarded several prizes. The resulting TP is merged with the raising adjective likely to derive the AP likely to be awarded several prizes. This AP is subsequently merged with the passive verb thought to form the VP thought likely to be awarded several prizes. This in turn merges with the passive auxiliary be, forming the T-bar shown in simplified form in (2) below (where the notation BE indicates that the morphological form of the relevant item hasn’t yet been determined):

The tense auxiliary [T BE] needs to agree with an appropriate nominal within the structure containing it. Given Pesetsky’s Earliness Principle (which requires operations to apply as early as possible in a derivation), T-agreement must apply as early as possible in the derivation, and hence will apply as soon as BE is introduced into the structure. On the assumption that c-command is central to syntactic operations, T will agree with a nominal (i.e. a noun or pronoun expression) which it c-commands. Accordingly, as soon as the structure in (2) is formed, [T BE] searches for a nominal which it c-commands to agree with.

To use the terminology introduced by Chomsky (1998, 1999, 2001), by virtue of being the highest head in the overall structure at this point in the derivation, BE serves as a probe which searches for a c-commanded nominal goal to agree with. The only nominal goal c-commanded by [T BE] within the structure in (2) is the QP several prizes: [T BE] therefore agrees in person and number with several prizes, and so is ultimately spelled out as the third-person-plural form are in the PF component. Chomsky refers to person and number features together as  -features (where

-features (where  is the Greek letter phi, pronounced in the same way as fie in English): using this terminology, we can say that the probe [T BE] agrees in

is the Greek letter phi, pronounced in the same way as fie in English): using this terminology, we can say that the probe [T BE] agrees in  -features with the goal several prizes. Subsequently, expletive there is merged in spec-TP to satisfy the [EPP] requirement for T to project a specifier, and the resulting TP is in turn merged with a null declarative complementizer to form the CP shown in simplified form below (which is the structure of (1) above):

-features with the goal several prizes. Subsequently, expletive there is merged in spec-TP to satisfy the [EPP] requirement for T to project a specifier, and the resulting TP is in turn merged with a null declarative complementizer to form the CP shown in simplified form below (which is the structure of (1) above):

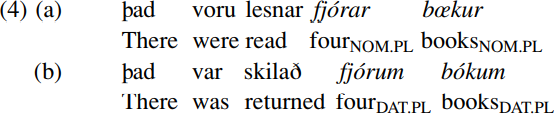

However, there are a number of details which we have omitted in (3); one relates to the case assigned to the complement (several prizes) of the passive participle awarded. Although case is not overtly marked on the relevant noun expressions in English, evidence from languages like Icelandic with a richer case system suggests that the complement of a passive participle in finite expletive clauses is assigned nominative case via agreement with T – as the following contrast (from Sigurðsson 1996, p. 12) illustrates:

In (4a), the auxiliary voru is a third-person-plural form which agrees with the NOM.PL/nominative plural complement fjorar bœkur ´ ‘four books’. In (4b), the auxiliary is the agreementless form var ‘was’, and the complement of the passive participle is DAT.PL/dative plural. (Var is a third-person-singular form, but can be treated as an agreementless form if we characterize agreement by saying that ‘An auxiliary is first/second person if it agrees with a first/second-person subject, but third person otherwise; it is plural if it agrees with a plural subject, but singular otherwise.’ This means that a third-person-singular auxiliary can arise either by agreement with a third-person-singular expression or – as here – can be a default form used as a fall-back when the auxiliary doesn’t agree with anything.) Sigurðsson argues that it is an inherent lexical property of the participle skila ‘returned’ that (like around a quarter of transitive verbs in Icelandic) it assigns so-called inherent dative case to its complement (see Svenonius 2002a,b on dative complements), and (because it can’t agree with a non-nominative complement) the auxiliary surfaces in the agreementless form var; by contrast, the participle lesnar ‘read’ in (4a) does not assign inherent case to its complement, and instead the complement is assigned (so-called) structural nominative case via agreement with the past-tense auxiliary voru ‘were’.

Icelandic data like (4) suggest that there is a systematic relationship between nominative case assignment and T-agreement: they are two different reflexes of an agreement relationship between a finite T probe and a nominal goal. In consequence of the agreement relationship between the two, the T probe agrees with a nominal goal which it c-commands, and the nominal goal is assigned nominative case. Accordingly, several prizes in (3) receives nominative case via agreement with [T are]. (It should be noted in passing that we focus on characterizing syntactic agreement. On so-called ‘semantic agreement’ in British English structures like The government are ruining the country, see den Dikken 2001 and Sauerland and Elbourne 2002.)

The approach to case assignment outlined here (in which subjects are assigned nominative case via agreement with a finite T), where we suggested that subjects are case-marked by a c-commanding C constituent. But in one sense, our revised hypothesis that finite subjects are casemarked by T is consistent with our earlier analysis. We argued that (in consequence of the Earliness Principle) a noun or pronoun expression is case-marked by the closest case-assigner which c-commands it: since we also assumed that subjects originate in spec-TP, it was natural to assume that they are case-marked by the closest functional head above them, namely C. But once we move to an analysis like that in which subjects originate internally within VP, our assumption that they are case-marked by the closest case-assigning head above them opens up the possibility that nominative subjects may be casemarked by T rather than by C – and indeed this is the assumption which we will make from now on (an assumption widely made in current research).

|

|

|

|

تفوقت في الاختبار على الجميع.. فاكهة "خارقة" في عالم التغذية

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

أمين عام أوبك: النفط الخام والغاز الطبيعي "هبة من الله"

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

قسم شؤون المعارف ينظم دورة عن آليات عمل الفهارس الفنية للموسوعات والكتب لملاكاته

|

|

|