Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension|

Read More

Date: 13-5-2022

Date: 21-2-2022

Date: 23-4-2022

|

The Humanists reacted to a large extent against the medieval Scholastics, who promoted a form of rational thinking with precise formulation and expression of thought. The Humanists were of course not opposed to rational thinking and precise linguistic formulation; but they did emphasize the importance of the persuasive function of language; language, according to Humanist thinking, was not there solely to demonstrate; it was also there to persuade. This emphasis resulted in a rebirth of rhetoric, which is clearly reflected not only in literary texts but also in pragmatic ones.

In punctuation the Humanists therefore attempted to strike a balance between the logical relationships in syntactic structures and the rhetorical structure of a period. To some extent we still try to achieve that kind of balance, but the rhetorical element was much more to the fore in Renaissance texts. Our punctuation system is essentially logical and grammatical, as in the following piece of text:

(1) Shakespeare's work falls into three main periods: an initial period dominated by comedy, both lighthearted and serious, and history plays; a middle period including the great tragedies, the Roman plays, and the so-called 'problem plays'; and a final period consisting of the late comedies, sometimes called the 'romances'.

In that passage essential qualifications are not separated by a comma: there is not one before dominated, including and consisting. But the phrase both lighthearted and serious and the clause sometimes called the 'romances' are preceded by commas since those qualifications are non-essential and non-defining. Note also how the semicolons separate the larger units from the smaller ones within these, and how the colon, as is typical of today's usage, has been employed to introduce a particularizing explanation. As we shall see shortly, the Renaissance use of the colon was quite different. Renaissance pointing is essentially rhetorical and elocutionary,1 as can be seen in the next passage (2) from Francis Bacon's The Advancement of Learning. For comparison it is followed by a modern version (3).

(2) For as knowledges are now delivered, there is a kinde of Contract of Errour, betweene the Deliuerer, and the Receiuer: for he that deliuereth knowledge, desireth to deliuer it in such fourme, as may be best beleeued; and not as may be best examined: and hee that receiueth knowledge, desireth rather present satisfaction, than expectant Enquirie, & so rather not to doubt, than not to err: glorie making the Author not to lay open his weaknesse, and sloth making the Disciple not to knowe his strength.

(3) For as knowledges are now delivered, there is a kind of contract of error between the deliverer and the receiver. For he that delivereth knowledge desireth to deliver it in such form as may be best believed, and not as may be best examined; and he that receiveth knowledge desireth rather present satisfaction than expectant inquiry; and so rather not to doubt than not to err: glory making the author not to lay open his weakness, and sloth making the disciple not to know his strength. (Wright 1973: 170-171)

First of all note the generally heavy punctuation of (2). The many commas often emphasise contrastive units: there is a kinde of Contract of Errour, betweene the Deliuerer, and the Receiuer. Similarly in the rhetorical parison of rather present satisfaction, than expectant Enquirie. What is perhaps even more noteworthy is the use of the colon. Passage (3) has only one, signalling the particularising conclusion, whereas (2) has three, separating persuasively and elegantly the steps of the argument in a single sentence:

Step 1: Introduction of Deliuerer and Receiuer.

Step 2: Deliuerer.

Step 3: Receiuer.

Step 4: Conclusion: the kind of contract of error that exists between deliverer and receiver results in glory for the author (deliverer) since by delivering his knowledge in such a way as it may be best believed, not examined, he does not lay himself open to weakness (by the receiver objecting). The 'contract' also results in sloth for the receiver since he does not employ his strength, i.e. the force of argument he might adduce against the deliverer if the argument or statement had been examined properly.

Bacon's semicolon stresses the antithetical parison of best beleeued and best examined, i.e. a contrast within the antithesis of deliuereth (line 2) and receiueth (line 4), marked by the second colon, a heavier rhetorical punctuation mark than the semicolon. There is no semicolon before & so rather not to doubt because we have already had the antithesis in rather present satisfaction, than expectant Enquirie. That is why the semicolon in that position in text (3) is too heavy, distorting Bacon's more subtly persuasive use of that punctuation mark. On the other hand, full stops would be too heavy for Bacon. They would not have the connective force that the colons retain, for although they separate, they also connect the steps in argument. The punctuation in the modern version ruins this rhetorically parallel balance by having three different marks for Bacon's three colons, viz. full stop, semicolon and colon.

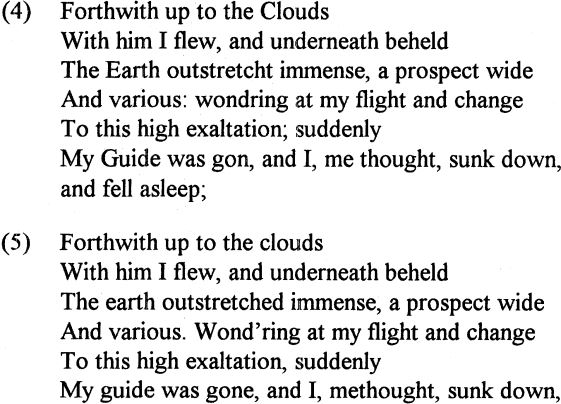

Let us now move to an example from fictional literature in order to illustrate briefly how a return to Renaissance punctuation in editions of Renaissance texts can be beneficial to the reading of a passage. The following lines are from Book V, lines 86-92, of Milton's Paradise Lost. The first quotation (4) is from Beeching's edition of 1914, which follows faithfully that of 1667; the second (5) is from Douglas Bush's 1966 version. We have examples of Milton's own punctuation in his manuscript of Book I of Paradise Lost, and when this is compared with Book I of the 1667 edition, we note thatt the printers made hardly any changes to Milton's pointing practice. We are thus justified in assuming the same to be the case in the rest of the poem as it appears in the 1667 (and Beeching's) edition:

Being relatively heavy, the colon before wondring in (4) foregrounds by subtle rallentando Eve's suspended amazement. This delightful effect would be impossible if modern practice were followed, and it is certainly absent from Bush's version. His full stop has too much separating force, particularly since he elects to place only a comma before suddenly, thereby creating an unattached participial clause preceding it: it can hardly be the guide (Satan) who is wonderstruck at being airborne.

Pausal reasons for punctuation are particularly significant in drama, where, during the Renaissance, they were closely connected with the effects of rhetoric in stage performance. The remaining examples are from Heminge and Condell's First Folio edition (1623) of Shakespeare whose own pointing practice is unknown, except perhaps for the punctuation in a section of Thomas More, the manuscript of which may be Shakespeare's. However, we do know what general Renaissance practice was, although we must be on our guard: some printers could be highly idiosyncratic or even incompetent. All the same, close examination of the First Folio and of the good quartos gives us a positive picture of elocutionary pointing, frequently serving as a guide to the actor in ways considerably different from today's. By the 18th century the punctuation we find in Elizabethan plays may be described as a lost art, clearly not appreciated or understood by Samuel Johnson when, referring to his editorial work on Shakespeare, he said: "In restoring the author's works to their integrity, I have considered the punctuation as wholly in my power; for what could be their care of colons and commas, who corrupted words and sentences" (Sherbo 1968).

From Dr Johnson onwards editors of Shakespeare have been generally contemptuous of Elizabethan punctuation. It is important to realize that much of it was geared towards highlighting rhetoric (which, it may be noted in passing, did not find much scholarly favor and attention after the 18th century until the 1970s) and suggesting to the actor how to speak his lines. Percy Simpson's pioneering book Shakespearian Punctuation (1911) shows quite unambiguously that what could not be done in Johnson's day and cannot be done in ours (if we keep adhering rigidly to the present logico-grammatical system), could be done in Shakespeare's, before the advent of Cartesian rationalist formalism, which changed considerably occidental views of language.

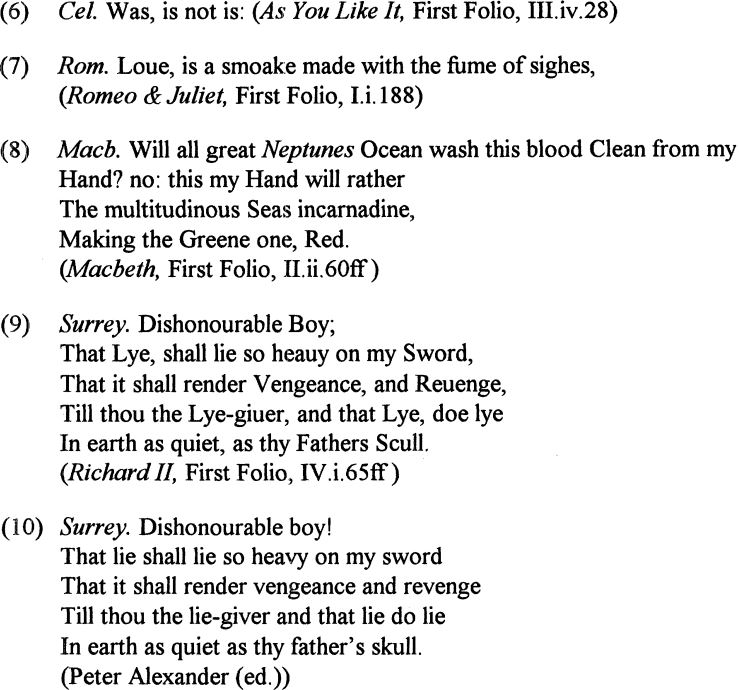

The First Folio having no line numbers, line references to quotations from it have been added for the reader's convenience and follow the complete-works edition by Peter Alexander (1951). We shall start with four typical examples of emphatic pointing

Commas in (6), (7) and (8) illustrate the mark being used to emphasise or stress a preceding word. In (6) it shows that Celia's remark is metalinguistic: "'Was' is not 'is'". Quotation marks did not become current until the 18th century. The comma in (7) tells the actor playing Romeo to dwell on a word particularly prominent in this scene; and the last line of (8) should tell editors that only one interpretation is likely here, viz. the reading that takes one as a stressed modifier of Red ('completely red') and not as a headword with Greene as a modifier, seen as a possible interpretation by, for instance, Hunter in his Penguin edition, 1967. The heavy pointing of (9), which can usefully be compared with (10), clearly draws rhetorical attention to the ploce and antanaclasis of Lye/lie/lye, and to the epanalepsis of Venge-/-uenge in the third line. The next passage shows light pointing:

The light punctuation is particularly marked in the use of only commas at the end of the first and fifth lines. This and the rhymed verse are in perfect keeping with the otherworldly, fleet-footed spirit of Robin Goodfellow (=Puck), the passage following hard on his famous 'Over hill, over dale'.

The final extract is Portia's famous speech from The Merchant of Venice, first from the First Folio, then from Alexander's edition by way of comparison:

This famous speech has all the hallmarks of judicial rhetoric and can be divided into the classically rhetorical units of exordium, narratio, refutatio and conclusio. The Folio pointing highlights the considerable effect of this.

The first sentence covers the introduction {exordium) of the key concept of mercy with only the lightest of punctuation marks used. Then follows the narratio, which is in two parts, each with a climax: the first narratio section ends on the climactic Crowne (line 6) and moves there swiftly with light pointing to give the full stop its maximum crowning effect, which is lost completely in the modern version with its semicolon after mightiest slowing down the flow and without the culminating force of the stop after crown.

The second part of the narratio - stopping equally climactically with another key word, Justice, in line 14 - has two subtle uses of the heavier marks. The first of these, the colon after Kings in 9, signals a rhetorical pause before the significantly contrastive But in the argument. Here Alexander makes do with a semicolon because of the much narrower, particularising use of our colon (as in 3, holding up the steady flow towards the first climax), which would therefore be confusing here in modern punctuation. The semicolon in 12 (the only one in the passage) eloquently emphasises God himselfe.

The refutatio follows until the next full stop in 19. Note how the comma in 16 rhetorically stresses both Iustice and none of vs. Even more prominent and expressive is the colon's highlighting of the word salvation, a very significant concept in the argument because of its relation to the key issues of the whole speech: justice versus mercy. Considering only justice does not lead to salvation, but considering mercy does. The comma after prayer (18) eloquently draws attention to the thematic polyptoton with pray in the preceding line; and the horror of Antonio's possible fate, expressed in the last two lines of the conclusio, is foregrounded by a final rhetorical colon. No such foregrounding is suggested by the modern version.

Although it may sometimes be dangerous to rely fully on Renaissance punctuation as an indication of the author's usage, there is enough evidence to suggest that without a close study of Renaissance pragmatic pointing practice we do ourselves a serious disservice. Especially during the latter part of the 16th century and a good part of the 17th, punctuation helps us to understand the Renaissance reception of text, giving us a clearer picture of how linguistic structures were used in tandem with rhetorical principles for persuasion, both in logical argument (logos) but also, and perhaps above all, within the other two fields of the famous Aristotelian rhetorical triad, viz. ethos and pathos. Perhaps now, with the considerable upsurge of interest in rhetoric, it is time for editors of Renaissance drama, at least, to present their texts in accordance with the original views of rhetorical syntax, suggested so powerfully by the original punctuation. In the words of Pollard: "The only rule for dealing with these supra-grammatical stops is to read the passage as punctuated, and then consider how it is affected by the pause at the point indicated. In the same way, if there is no stop where we expect one, or only a comma where we should expect a colon or even a full stop, we must try how the passage sounds with only light stops or none at all, and see what is the gain or loss to the dramatic impression" (Pollard 1917).

|

|

|

|

دخلت غرفة فنسيت ماذا تريد من داخلها.. خبير يفسر الحالة

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

ثورة طبية.. ابتكار أصغر جهاز لتنظيم ضربات القلب في العالم

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

قسم شؤون المعارف ووفد من جامعة البصرة يبحثان سبل تعزيز التعاون المشترك

|

|

|