Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension|

Read More

Date: 2023-10-10

Date: 2023-08-26

Date: 2023-08-02

|

Inflection in English

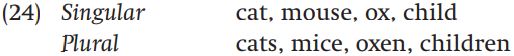

As we’ve seen in passing in the sections above, English is a language that is quite poor in inflection. The distinction between singular and plural is marked on nouns:

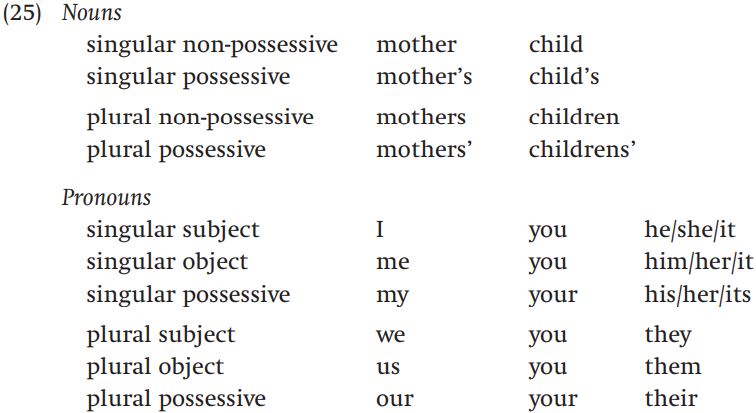

English has only a tiny bit of case marking on nouns: it uses the morpheme -s (orthographically -’s in the singular, -s’ in the plural) to signal possession, the remnant of the genitive case. Pronouns, however, still exhibit some case distinctions that are no longer marked in nouns:

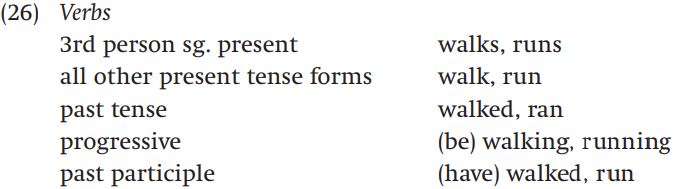

In verbs, number is only marked in the third person present tense, where -s signals a singular subject. As we’ve seen, English verbs inflect for past tense, but not for future, and there are two participles (present with –ing and past with -ed) that together with auxiliary verbs help to signal various aspectual distinctions:

Distinctions in aspect and voice are expressed in English through a combination of auxiliary choice and choice of participle. The progressive, which expresses, among other things, on-going actions, is formed with the auxiliary be plus the present participle:

The perfect (note that the perfect is not the same as the perfective, which we discussed above) expresses something that happened in the past but still has relevance to the present. This is signaled in English with the past participle and a form of the auxiliary have:

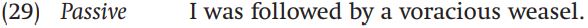

The passive voice in English is formed with the past participle as well, but the auxiliary be is used instead of have:

It is, of course, possible to combine various auxiliaries and participial forms to express tense/aspect distinctions that are quite complex, as in, for example, the past perfect progressive passive sentence I had been being followed by a voracious weasel.

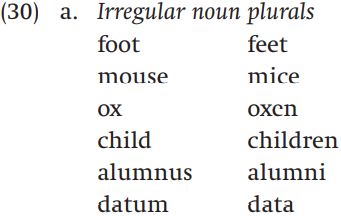

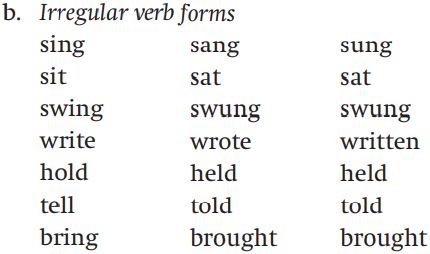

As you can see in (25)–(29), English has both regular and irregular inflections. All of our regular inflections are suffixal, but irregular forms are often formed by internal stem change (ablaut and umlaut) or by a combination of internal stem change and suffixation. Examples of irregular forms are given in (30):

We could no doubt think of more examples as well. It is often said that the irregular plurals and past tenses in English form closed classes; that is, they constitute a fixed list from which particular forms can be lost, but to which no new forms can be added. The regular plural and past tense endings are considered default endings. In other words, when a new noun is added to English, its plural is formed with -s and when a new verb is added, its past tense is formed with -ed. So if we borrow a noun from another language or coin a completely new noun, their plurals will be formed with the regular suffix (fajitas, wugs). Similarly for new verbs (googled).

Why do we have irregular forms? In some cases, they are the remnants of ways of forming the plural or past tense that we no longer have today. We saw in chapter 5 that plurals like foot ~ feet and mouse ~ mice are the remnants of a rule of umlaut that was lost at the earliest stages of English. The irregular verbs are also a remnant of a way of inflecting verbs that goes all the way back to the Germanic ancestor of English and even beyond that to the way of inflecting verbs in proto-Indo-European. The details of how that kind of inflection worked need not concern us here, except to say that it involved internal vowel changes (ablaut). Suffice it to say that that form of inflection is no longer used to inflect new verbs in English.

|

|

|

|

دراسة: عدم ترتيب الغرفة قد يدل على مشاكل نفسية

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

علماء: تغير المناخ تسبب في ارتفاع الحرارة خلال موسم الحج

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

العتبة العباسية تطلق المؤتمر العلمي لأسبوع الإمامة باللغة الإنجليزية

|

|

|