تاريخ الرياضيات

تاريخ الرياضيات

الرياضيات في الحضارات المختلفة

الرياضيات في الحضارات المختلفة

الرياضيات المتقطعة

الرياضيات المتقطعة

الجبر

الجبر

الهندسة

الهندسة

المعادلات التفاضلية و التكاملية

المعادلات التفاضلية و التكاملية

التحليل

التحليل

علماء الرياضيات

علماء الرياضيات |

Read More

Date: 20-2-2016

Date: 20-2-2016

Date: 28-2-2016

|

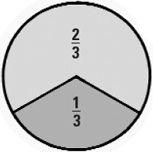

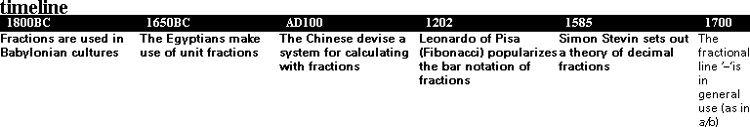

A fraction is a ‘fractured number’ – literally. If we break up a whole number an appropriate way to do it is to use fractions. Let’s take the traditional example, the celebrated cake, and break it into three parts.

The person who gets two of the three parts of the cake gets a fraction equivalent to ⅔. The unlucky person only gets ⅓. Putting together the two portions of the cake we get the whole cake back, or in fractions, ⅓ + ⅔ = 1 where 1 represents the whole cake.

Here is another example. You might have been to the sales and seen a shirt advertised at four-fifths of the original price. Here the fraction is written as ⅘. We could also say the shirt has a fifth off the original price. That would be written as ⅕ and we see that ⅕ + ⅘ = 1 where 1 represents the original price.

A fraction always has the form of a whole number ‘over’ a whole number. The bottom number is called the ‘denominator’ because it tells us how many parts make the whole. The top number is called the ‘numerator’ because it tells us how many unit fractions there are. So a fraction in established notation always looks like

In the case of the cake, the fraction you might want to eat is ⅔ where the denominator is 3 and the numerator is 2. ⅔ is made up of 2 unit fractions of ⅓.

We can also have fractions like 14/5 (called improper fractions) where the numerator is bigger than the denominator. Dividing 14 by 5 we get 2 with 4 left over, which can be written as the ‘mixed’ number 2⅘. This comprises the whole number 2 and the ‘proper’ fraction ⅘. Some early writers wrote this as ⅘2. Fractions are usually represented in a form where the numerator and denominator (the ‘top’ and the ‘bottom’) have no common factors. For example, the numerator and denominator of 8/10 have a common factor of 2, because 8 = 2 × 4 and 10 = 2 × 5. If we write the fraction 8/10 = 2×4/2×5 we can ‘cancel’ the 2s out and so 8/10 = ⅘, a simpler form with the same value. Mathematicians refer to fractions as ‘rational numbers’ because they are ratios of two numbers. The rational numbers were the numbers the Greeks could ‘measure’.

Adding and multiplying

The rather curious thing about fractions is that they are easier to multiply than to add. Multiplication of whole numbers is so troublesome that ingenious ways had to be invented to do it. But with fractions, it’s addition that’s more difficult and takes some thinking about.

Let’s start by multiplying fractions. If you buy a shirt at four-fifths of the original price of £30 you end up paying the sale price of £24. The £30 is divided into five parts of £6 each and four of these five parts is 4 × 6 = 24, the amount you pay for the shirt.

Subsequently, the manager of the shop discovers that the shirts are not selling at all well so he drops the price still further, advertising them at ½ of the sale price. If you go into the shop you can now get the shirt for £12. This is ½ × ⅘ × 30 which is equal to 12. To multiply two fractions together you just multiply the denominators together and the numerators together:

If the manager had made the two reductions at a single stroke he would have advertised the shirts at four-tenths of the original price of £30. This is 4/10 × 30 which is £12.

Adding two fractions is a different proposition. The addition ⅓ + ⅔ is OK because the denominators are the same. We simply add the two numerators together to get 3/3, or 1. But how could we add two-thirds of a cake to fourfifths of a cake? How could we figure out ⅔ + ⅘? If only we could say ⅔ + ⅘ = 2+4/3+5 = 6/8 but unfortunately we cannot.

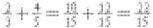

Adding fractions requires a different approach. To add ⅔ and ⅘ we must first express each of them as fractions which have the same denominators. First multiply the top and bottom of ⅔ by 5 to get 10/15. Now multiply the top and bottom of ⅘ by 3 to get 12/15. Now both fractions have 15 as a common denominator and to add them we just add the new numerators together:

Converting to decimals

In the world of science and most applications of mathematics, decimals are the preferred way of expressing fractions. The fraction ⅘ is the same as the fraction 8/10 which has 10 as a denominator and we can write this as the decimal 0.8.

Fractions which have 5 or 10 as a denominator are easy to convert. But how could we convert, say ⅞, into decimal form? All we need to know is that when we divide a whole number by another, either it goes in exactly or it goes in a certain number of times with something left over, which we call the ‘remainder’.

Using ⅞ as our example, the recipe to convert from fractions to decimals goes like this:

• Try to divide 8 into 7. It doesn’t go, or you could say it goes 0 times with remainder 7. We record this by writing zero followed by the decimal point: ‘0.’

• Now divide 8 into 70 (the remainder of the previous step multiplied by 10). This goes 8 times, since 8 × 8 = 64, so the answer is 8 with remainder 6 (70 − 64). So we write this alongside our first step, to make ‘0.8’

• Now divide 8 into 60 (the remainder of the previous step multiplied by 10). Because 7 × 8 = 56, the answer is 7 with remainder 4. We write this down, and so far we have ‘0.87’

• Divide 8 into 40 (the remainder of the previous step multiplied by 10). The answer is exactly 5 with remainder zero. When we get remainder 0 the recipe is complete. We are finished. The final answer is ‘0.875’.

When applying this conversion recipe to other fractions it is possible that we might never finish! We could keep going forever; if we try to convert ⅔ into decimal, for instance, we find that at each stage the result of dividing 20 by 3 is 6 with a remainder of 2. So we have again to divide 6 into 20, and we never get to the point where the remainder is 0. In this case we have the infinite decimal 0.666666… This is written 0.6 to indicate the ‘recurring decimal’.

There are many fractions that lead us on forever like this. The fraction 5/7 is interesting. In this case we get 5/7=0.714285714285714285... and we see that the sequence 714285 keeps repeating itself. If any fraction results in a repeating sequence we cannot ever write it down in a terminating decimal and the ‘dotty’ notation comes into its own. In the case of 5/7 we write 5/7 =  .

.

Egyptian fractions

Egyptian fractions

The Egyptians of the second millennium BC based their system of fractions on hieroglyphs designating unit fractions – those fractions whose numerators are 1. We know this from the Rhind Papyrus which is kept in the British Museum. It was such a complicated system of fractions that only those trained in its use could know its inner secrets and make the correct calculations.

The Egyptians used a few privileged fractions such as ⅔ but all other fractions were expressed in terms of unit fractions like ½, ⅓, ⅟11 or 1/168. These were their ‘basic fractions’ from which all other fractions could be expressed. For example 5/7 is not a unit fraction but it could be written in terms of the unit fractions,

where different unit fractions must be used. A feature of the system is that there may be more than one way of writing a fraction, and some ways are shorter than others. For example,

The ‘Egyptian expansion’ may have had limited practical use but the system has inspired generations of pure mathematicians and provided many challenging problems, some of which remain unsolved today. For instance, a full analysis of the methods for finding the shortest Egyptian expansion awaits the intrepid mathematical explorer.

the condensed idea

One number over another

|

|

|

|

دراسة يابانية لتقليل مخاطر أمراض المواليد منخفضي الوزن

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

اكتشاف أكبر مرجان في العالم قبالة سواحل جزر سليمان

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

اتحاد كليات الطب الملكية البريطانية يشيد بالمستوى العلمي لطلبة جامعة العميد وبيئتها التعليمية

|

|

|