Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension

Teaching Methods

Teaching Methods| Evaluative adverbs and dialogue - Evaluatives as ancillary commitments |

|

|

|

Read More

Date: 2024-01-02

Date: 24-2-2022

Date: 1-3-2022

|

Evaluative adverbs and dialogue - Evaluatives as ancillary commitments

It has been said in the preceding section that the content of the evaluative adverb is not part of the main content of the sentence in which it occurs. On the other hand, we have also suggested that the speaker is somehow committed to the evaluative comment. We now turn to the special pragmatic status of evaluatives, which accounts for this intriguing double behavior.

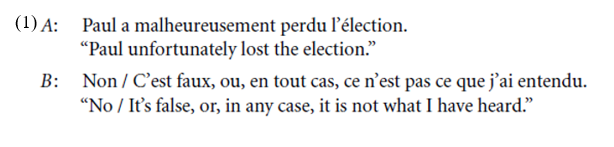

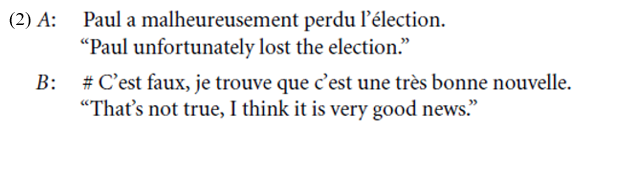

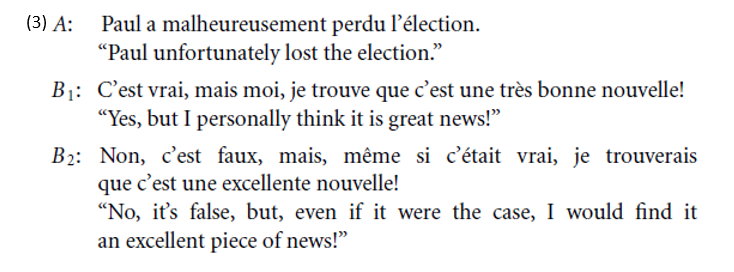

As observed by Jayez and Rossari (2004), evaluatives cannot be challenged by the other discourse participants, at least with ordinary means. Compare the dialogues in (1) and (2). On the other hand, evaluatives can be challenged by a speaker who, at the same time, accepts or rejects the main content (Potts 2005: 51). This requires a special form of answer, such as yes . . . but (3).

This data makes sense if the evaluative adverb denotes the judgment of the speaker independently of the other commitments associated with his discourse. We will say that the evaluative conveys an ancillary commitment of the speaker.

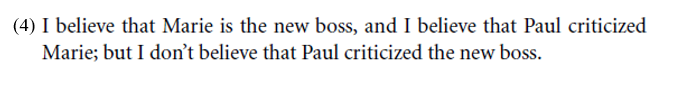

Assuming that evaluative adverbs convey a commitment of the speaker independent of that effected by the main speech act directly accounts for the two basic semantic properties. Since the adverb does not contribute to the main speech act, this speech act gets effected just as if the adverb were absent. Thus if the utterance is an assertion, the speaker is committed to the truth of the proposition conveyed by the sentence without the adverb. As for non-opacity, since we assume that evaluative adverbs take a propositional argument, nothing in their semantics precludes them from triggering opacity. However their special pragmatic status has the required effect. The crucial observation here is that we are dealing with the beliefs of a single agent. If he says (1b), the speaker (assuming sincerity) indicates he believes that (i) Marie is the new boss, (ii) Paul criticized Marie, and (iii) it is unfortunate that Paul criticized Marie. While it is possible for an agent to have contradictory beliefs, it is not so easy to knowingly entertain contradictory beliefs. Thus for a speaker to say (1b) and still deny that Paul unfortunately criticized the new boss would be akin to his asserting (4), which is clearly odd. Thus, just as first person attitude reports are ordinary attitude reports with a special pragmatic status that bars opacity, we assume that evaluative adverbs are proposition modifiers with a special pragmatic status.

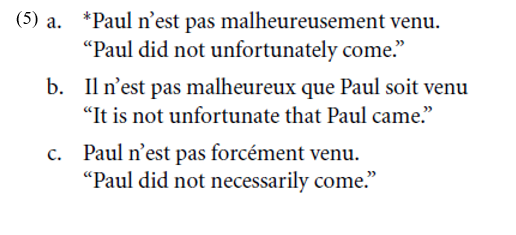

This ancillary commitment hypothesis also explains a well-known observation, which nevertheless has resisted syntactic or logical accounts: in contrast with evaluative adjectives, evaluative adverbs cannot be in the scope of negation.

This cannot be due to type mismatch. First, the negation is also an operator taking a proposition argument, so it suffices that the evaluative does not change the type of the expression it combines with (i.e., that it denotes a function from propositions to propositions) for the negation to find the right argument type. Second, some modal adverbs can occur in the scope of the negation (5c). Note that the scope of (prosodically integrated) postverbal adverbs follows order: an adverb has scope over adverbs on its right. Accordingly, the only possible argument of the evaluative in (5a) is come(p). Thus, according to our analysis, (5a) commits the speaker to the two propositionsi.While these are not contradictory, it is quite odd for a speaker to engage in conditional talk about a proposition which he simultaneously asserts to be false. While this may be done using counterfactuals, it seems that explicit marks of counter factuality is needed for it to be felicitous.

To summarize, evaluatives do not contribute to the main content of the sentence, but they imply a commitment on the part of the speaker. Several analyses have been proposed. The first attempt consisted in associating sentences with evaluatives with two speech acts, one for the main content, and one for the evaluative content (Bartsch 1976; Bellert 1977). Although these analyses delineate the problem, they do not deal with the asymmetric status of the two contents, which do not have the same role in dialogue, as shown above. More recently, Bach (1999) suggested that expressions such as evaluatives constitute ancillary propositions, which are distinct from the main content, but can nevertheless be asserted at the same time as the main content (secondarily). Their occurrence in interrogative sentences noted earlier, where they are not included in the question content and the query speech act, raises a serious problem for this proposal. It seems that we need an ancillary assertion in addition to the query; it is not clear, then, what the difference is with the two speech act proposal. Finally, in two concomitant analyses (Jayez and Rossari 2004; Potts 2005), evaluatives are seen as a case of conventional implicatures in Grice’s (1975) sense: although they are not part of “what is said,” their semantic content is encoded in the grammar. Accordingly, they contribute to an independent dimension of content. While we believe these analyses to be on the right track, they fall short of accounting for the special dialogical status of evaluatives observed in (1–3): we still need to work out what the dialogical status of that independent dimension is. We thus propose an analysis of the pragmatics of evaluatives, integrated in a model of dialogue, a slightly modified version of Ginzburg (2004).

|

|

|

|

حقن الذهب في العين.. تقنية جديدة للحفاظ على البصر ؟!

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

علي بابا تطلق نماذج "Qwen" الجديدة في أحدث اختراق صيني لمجال الذكاء الاصطناعي مفتوح المصدر

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

مشاتل الكفيل تنتج أنواعًا مختلفة من النباتات المحلية والمستوردة وتواصل دعمها للمجتمع

|

|

|