Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension|

Read More

Date: 2023-04-05

Date: 2023-10-20

Date: 2023-08-14

|

Until quite recently psychology has had relatively little to offer toward an understanding of semantic problems. It has generally been the case that while notions of meaning have been entertained by psychologists they were not done so for the purpose of explicating anything about language but for the purpose of explicating something about learning principles. Ever since the work of Ebbinghaus in the late nineteenth century, words or nonsense words have served as convenient stimuli and responses for psychologists exploring aspects of the learning process. Ebbinghaus’ own preference for using the nonsense word became predominant in research and it was not until the 1930s that natural words began to be employed to any significant degree. Attention then became focused on the use of meaning as an independent variable with the thought that variations in the meaning of words might have a differential learning effect.

Almost all research utilizing meaning as a variable since that time has centered about the question, Does similarity of meaning facilitate (or inhibit) the learning of responses to stimuli? Such a question appeared basic since a sentence was conceived of as a sequence of words. The problem was to explain under what conditions the words became associated to one another. Experiments were (and still are) designed to determine the basis of word association and a variety of paradigms were used such as those of paired associates, transfer, and retroactive inhibition.

Actually it has only been since the work of Osgood, Miller, Skinner, Brown and Carroll in the 1950s that psychologists have become a part of the twentieth century intellectual boom in the study of language. The work of the anthropologist, the philosopher, and of the linguist, in particular, has confronted the psychologist with an array of language phenomena which he had heretofore not considered. Since such phenomena require explication within some theoretical framework, psychological theorists have been active in attempting to account for them. All of the papers strongly reflect in some way or other interdisciplinary influences. Those by Osgood, Fodor, Lenneberg, McNeill, and Beverand Rosenbaum attempt to provide a theoretical framework with which to deal with semantic problems, while Miller’s offers experimental procedures which attempt to determine semantically relevant units.

Theorists have typically attempted to meet the challenge of new problems in three different and opposing ways; (1) by accounting for the phenomena with existing behavioristic theory, e.g., Skinner; (2) by modifying existing behavioristic theory, e.g., Osgood and Staats; or (3) by proposing new theory, e.g., Chomsky and his colleagues Miller, Lenneberg, Fodor, McNeill, Bever and Garrett. The introduction of new problems and alternative theories (especially Chomsky’s) has thus resulted in a serious questioning of the credibility of a behavioristic explanation of language phenomena.

The essence of the Chomskyan position is perhaps best summarized in a recent paper by Chomsky (1967 a) in which he considers the problem of designing a model of language-acquisition, i.e., an abstract language acquisition device that duplicates certain aspects of the achievement of the person who succeeds in acquiring linguistic competence. Chomsky views himself as holding a rationalist conception of acquisition of knowledge where ‘we take the essence of this view to be that the general character of knowledge, the categories in which it is expressed or internally represented, and the basic principles that underlie it, are determined by the nature of the mind. In our case, the schematism assigned as an innate property to the language acquisition device determines the form of knowledge (in one of the many traditional senses of “form”). The role of experience is only to cause the innate schematism to be activated and then to be differentiated and specified in a particular manner’ (p. 9).

The innate schematism which Chomsky refers to incorporates ‘ a phonetic theory that defines the class of possible phonetic interpretations; a semantic theory that defines the class of possible semantic representations; a schema that defines the class of possible grammars; a general method for interpreting grammar that assigns a semantic and phonetic interpretation to each sentence, given a grammar; a method of evaluation that assigns some measure of “complexity” to grammars. . . .[Thus] the given schema for grammar specifies the class of possible hypotheses; the method of interpretation permits each hypothesis to be tested against the input data; the evaluation measure selects the highest valued grammar compatible with the data ’ (pP. 7-8).

Chomsky thus posits that certain ideas (knowledge) are inherent in man’s nature and that when such innate ideas are activated through experience they become functional for him. When Descartes proposed this doctrine in the seventeenth century, he was vigorously criticized by the British empiricists, particularly Locke. Locke held that all knowledge is derived from experience, and that sensation (from objects in the external world) and reflection (an awareness of operations in our own mind) were the only two sources of experience. He denied the notion that the mind incorporates innate ideas which are independent of experience. Nothing could be in the intellect which was not first in the senses. Simple ideas, the result of sensation and reflection, were considered the basis of thought and the units with which all complex ideas were composed. Locke, however, did not deny the existence of abstract ideas. The denial of abstract ideas was espoused by Berkeley and other empiricist philosophers like James Mill. He postulated instead a strict elementarism based on sensation in which complex ideas were the simple sum of simple ideas. For Mill, simple ideas became complex ones through principles of association. Certain notions of Bentham’s utilitarianism, that human activity could be accounted for in terms of seeking pleasure and avoiding pain, were also incorporated into Mill’s philosophy. Some of the essential doctrines of behaviorism are thus represented in Mill: elementarism with respect to ideas (knowledge), the principles of association, and the Law of Effect (or the principle of reinforcement) to account for learning when sheer frequency and continguity of association were considered insufficient.

The focus upon behavior in psychology was largely the result of Watson’s writing in the early part of this century. For Watson, mind was considered something extranatural and illusory. Consciousness and mental processes were rejected as subjects of study and their very existence doubted because they could not be directly observed by the senses. What was real was matter. Mind was a superstition and any investigation concerning it was believed to be unscientific. Human psychology was to be accounted for in terms which were wholly behavioral. The description of behavior was to be made in terms of physiological processes or, preferably, in terms of the muscular or glandular activities which comprised such processes. Only the language of the physical world could provide objectivity.

Behavior was assumed to be composed of simple units like reflexes and all larger behavior units were assumed to be integrations of a number of stimulus-response connections. Such connections are formed through the process of conditioning which involves the operation of associationist principles. Since Watson held that conditioning is the simplest form of learning and the elementary process to which all learning is reducible, everything that a person may learn in a lifetime must therefore be derived from the simple muscular and glandular responses which the child produces in infancy. Thus, in place of the classical doctrine of the association of ideas, behaviorism substitutes the association of motor responses. An idea, if the term is to have any meaning at all for the behaviorist, is a unit of behavior. What a child inherits are physical bodily structures and their modes of functioning. It has neither general intelligence nor any mental traits. Emotions are not considered as matters of feeling but as bodily reactions.

Without mind, what then was ‘thought’ for Watson? Thoughts were laryngeal habits and such habits, he held, were developed from random unlearned vocalizations by conditioning. At first language is overt and then it becomes sub-vocal, at which point it becomes thinking. Thinking then is the making of implicit verbal reactions which, while not spoken speech, is still behavior. It is behavior but in the form of changes in tension among the various speech mechanisms. Such changes in tension were regarded as duplicating the movement involved in overt speech. No distinction is therefore made between language and thought. They are one and the same in accord with a materialist conception where only matter is considered real.

With respect to language, words were considered by Watson as substitutes for objects and concrete situations since it was believed that they evoked the same responses that the object and situations themselves elicited. (Both the Osgood and Fodor papers discuss the problems involved in this conception.) The meaning of a word is simply the conditioned response to that word. For example, suppose the word ‘ bottle ’ is uttered whenever a child is presented a bottle. Suppose, too, that the child reaches for the bottle when it is presented. After a number of repetitions of ‘bottle’ uttered, and the bottle presented and reached for, the child will produce the reaching response when only the word ‘bottle’ is uttered. The child has then, in Watson’s view, learned the meaning of the word, its meaning being the behavior which is elicited by it. Sentences were regarded as an association of words, a series of behavioral responses.

Skinner is one psychologist who has deviated very little from the original Watsonian behaviorism. Most other behaviorists have deviated, and some in relatively significant respects. One of the most significant changes (resulting in the prefix ‘neo’ to behaviorism) has involved the positing of unobserved events, termed intervening variables or hypothetical constructs by such psychologists as Hull and his student, Osgood. Still true to the materialist tenets of Watsonian behaviorism, however, such concepts are required to be specified in operational terms. That is, all concepts must be derived from empirical ultimates. For neo-behaviorists like Osgood, such ultimates are the data of observation, physical response units.

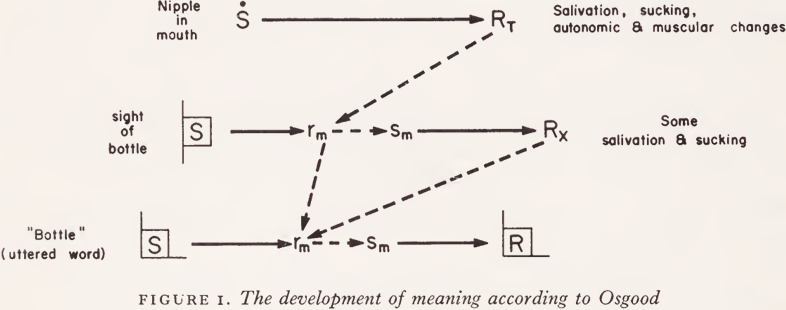

According to Osgood the cognitive content or meaning of perceived objects, events and words are derivable from behavior. If a stimulus object such as a bottle does not elicit a distinctive pattern of behavior it has no meaning, but will derive meaning through conditioning when it occurs with a stimulus which does produce a distinctive pattern of behavior. Such a potent stimulus might be a nipple in the mouth, as Osgood suggests, which elicits such behavior as sucking movements, milk ingestion, and autonomic and musculature changes. Figure i (from Osgood, 1964) illustrates the basis of the system.

The repeated presentation of the conditioned stimulus (Osgood’s  in Figure, i.e., the sight of a bottle) which originally does not elicit a distinctive pattern of behavior in contiguity with the unconditioned stimulus (S in Figure, i.e., the nipple of bottle touching the mouth) which does elicit a distinctive pattern of behavior (RT i e., salivation, sucking, etc.) results in the conditioned stimulus producing unobserved (rm) and observed (RX) behaviors. Both rm and RX are considered to be portions of the total behavior, RT. It is rm which Osgood designates as the meaning of the perceived object (‘ perceptual sign ’), bottle. Behaviors like glandular changes and minimal postural adjustments are those which Osgood has suggested (in earlier papers) are the most easily conditioned to become components of rm.

in Figure, i.e., the sight of a bottle) which originally does not elicit a distinctive pattern of behavior in contiguity with the unconditioned stimulus (S in Figure, i.e., the nipple of bottle touching the mouth) which does elicit a distinctive pattern of behavior (RT i e., salivation, sucking, etc.) results in the conditioned stimulus producing unobserved (rm) and observed (RX) behaviors. Both rm and RX are considered to be portions of the total behavior, RT. It is rm which Osgood designates as the meaning of the perceived object (‘ perceptual sign ’), bottle. Behaviors like glandular changes and minimal postural adjustments are those which Osgood has suggested (in earlier papers) are the most easily conditioned to become components of rm.

The meaning of words is derived in a similar fashion as the meaning of perceptual signs, that is, through conditioning. The meanings of words ([jp) can be derived directly from observed behavior (RT), or from the previously conditioned meaning (rm) and observed behavior (Rx) of perceptual signs (jJD). Words which have taken on meaning can also serve to provide meaning to other words (‘ assign ’ learning). In all cases, meaning is derived as a part of RT, Rx, or rm. Such a system of meaning, Osgood points out, does not involve any circularity since all meaning is derived from observable behavior. Thus the meaning of all words including such so-called abstract words as imagination, thought, god, theory, generative, necessity, and proposition is accounted for in the ultimate terms of physical response elements, as is the meaning of sentences. Whether or not this mediation view (the unobserved response, rm, ‘ mediates ’ between the observable stimulus and response) is to be considered as a reference theory of meaning is a question which Fodor discusses in his paper.

Fodor’s argument is essentially as follows. Single-stage conditioning accounts of Languagea2 are inadequate. This is so, because one absurd implication of the single- stage position is that a person would respond to words as he would to the referents of those words, e.g., a person would respond to the word fire as he does to actual fire. Although mediation theorists attempt to avoid this pitfall by the positing of an unobserved response (rm), nevertheless, Fodor claims mediation theory is reducible to single-stage theory. He contends that such a reduction must be made because mediationists hold to the postulate that there is a one-to-one correspondence between mediating (rm) and gross responses (RT) for the purpose of providing a sufficient condition for making reference. Thus, either the mediationist’s view of language is completely referential, or it is not referential at all. Either outcome, Fodor holds, is fatal to mediation theory.

For Fodor, acceptance of the one-to-one postulate implies that (observability aside) rm must equal RT. Thus, he is able to conclude that single-stage and mediation theories differ only in terms of observability and not in explanatory value. While Osgood agrees with Fodor that single-stage theory is inadequate and agrees to the holding of the one-to-one postulate, he does not agree that mediation theory can be reduced to single-stage theory. He holds while there is a one-to-one correspondence between rm and RT, nevertheless, rm does not equal RT (observability aside) and need not equal RT for a referring function to be made. To determine just what implications follow from acceptance of the one-to-one postulate is then the problem which must be resolved.3

The foregoing brief description of some of the essentials of Osgood’s theory is, I believe, basically representative of neo-behaviorist theorizing. Other neo- behaviorists, such as Staats (1967) and Berlyne, differ in many respects but not in any significant way especially when their views are compared with those of the Chomskyans. All neo-behavioristic theories derive ‘ ideas ’ from behavior with the utilization of principles of association. This is in sharp contrast to the Chomskyans who base the acquisition of knowledge on the notion of innate ideas and then rely essentially on some sort of matching principles which interact with experience in order to activate those ideas. The views of both of these camps contrast with those of such empiricists as Piaget and de-Zwart. These psychologists derive ideas from experience with the use of a modus operandi which a person inherits. Cognitive structures are generated as a result of this intellectual functioning.

For the behaviorist, ideas are ultimately composed of elements of behavior and in this sense are not abstract. On the other hand, neither the Chomskyans nor the Genevans (Piaget, de-Zwart, etc.) limit themselves to ideas based on the elements of the physical world, for they posit ideas which are purely abstract or mental. Ideas like transformations, deep structure, phrase marker, etc. cannot, they maintain, be reduced to physical terms. Given that behaviorists exclude such abstract ideas from their theory, it is not surprising that they sharply disagree with Chomsky’s view of language as a set of rules since most of Chomsky’s rules are abstract and involve a number of abstract entities. In the behaviorist view, sentences are constructed not by the application of rules but by the association of meaning constructs. The adequacy of the behaviorisms system which relies solely upon such a construct as rm and upon associationist principles has been challenged by Chomsky (1957) and by others such as Bever, Fodor and Garrett (1968).4 In his paper, Osgood attempts to justify the behaviorist system. This attempt cannot be regarded as successful, however, since Osgood does not specify precisely how any of the interesting language phenomena which he discusses (presuppositions, center-embedding, etc.) may be accounted for within his behaviorist system.

A summary of the essential characteristics of the various theoretical positions which have been discussed are indicated in Table 1. A question mark (?) has been placed next to those theorists whose position on all matters is uncertain.

Even though Piaget is an empiricist (see Piaget, 1968), it does seem that he could incorporate a generative grammar into his psychology. Some theorists, however, are of the opinion that one must adopt a neo-rationalist view of the acquisition of knowledge (innate ideas, etc.) if one wishes to adopt a generative grammar. De-Zwart (1969), for example, has stated that ‘ Because of this epistemological position [Chomsky’s innateness proposals] a psycholinguist who accepts Chomsky’s theories of generative grammars for particular languages, cannot at the same time reject his, be it tentative, model of language acquisition’ (p. 328). On the other hand, Goodman (1969) has stated that ‘ I can never follow the argument that starts with interesting differences in behavior between parallel phrases such as “ eager to please ” and “ easy to please ”; that characterizes these differences as matters of “ deep ” rather than “surface” structure; and that moves on to innate ideas’ (p. 138).

An empiricist generative position would be a viable one from Goodman’s point of view. In accord with such a position one could maintain that knowledge is derived from experience, and hold with Putnam (1967) and others (including perhaps Roger Brown) that any concept utilized in a grammar has a counterpart in general cognition and that such a counterpart is realized prior to language. Such notions as underlying structure, surface structure, transformation, grammatical categories and sentence could be viewed developing, therefore, through induction in non-linguistic contexts. The development of language is thus dependent on cognition.

In his paper, in this section, McNeill discusses the problem of whether language is entirely a function of general cognition (the condition for what McNeill terms a ‘ weak ’ linguistic universal) or whether it is a function of general cognition and a special linguistic ability (the condition for a ‘strong’ linguistic universal). While McNeill thinks it possible that both ‘weak’ and ‘strong’ universals may obtain, he propounds the thesis (as do the other Chomskyans) that humans possess and develop a special linguistic ability independent of general cognition.

Given the state of knowledge in psychology with respect to such topics as ‘ thought ’ and ‘ cognitive processes ’ and given the amount of uncertainty in linguistics with respect to what is called ‘ language universals ’, certainly no psychologist is in a position to gainsay McNeill’s formulation regarding the possibility of a special linguistic ability. However, even if our knowledge was further advanced, one is presented with unusual difficulties in attempting a satisfactory empirical resolution of the question as posed by McNeill. The fundamental obstacle to such a goal is what may be termed the translation problem. For in order to test the hypothesis that ‘sentence’ is or is not solely restricted to language, we must attempt a translation from linguistic constructs to non-linguistic constructs. We must know what to look for when we try to observe the possible occurrence of the concept in areas other than language. The question of what would constitute an adequate translation, however, is not an easy matter to determine. Considering the magnitude of the difficulties involved with regard to gathering relevant evidence, it is likely that McNeill’s notion of a special linguistic ability will be a viable hypothesis for a long while to come.

The neo-behaviorist, however, does not separate language from cognition. Osgood, for instance, regards the semantic component of language also as the cognitive system of man. The conception of the neo-behaviorists concerning the relations between language and cognition with respect to the understanding and production of speech is depicted in Figure 2. The conception of the Chomskyans is also shown. In sharp distinction to the behaviorists, the Chomskyans regard language (LANGUAGE KNOWLEDGE in Figure includes semantics) as a system which functions as a vehicle for thought (COGNITION in Figure), i.e., language is used to express and understand thought. The cognitive processes which result in or constitute thought are, however, unspecified.

A further distinction made by the Chomskyans, but not by the neo-behaviorists, is that of a separation between language knowledge and language use. Such a distinction is the basis of Chomsky’s competence-performance distinction where a theory of language is incorporated into a theory of language use.5 It is a theory of language use which involves the processes of understanding and production. Language knowledge (competence) interacts with rules pertaining to the use of such knowledge (Chomsky, this volume) as well as with conditions regarding memory, interest and the like to produce sentences or the understanding of them. With respect to production, a cognitive process yields a thought which in turn is expressed in language and uttered in speech. The reverse process would be that of understanding.

Chomsky has maintained that it would be ‘ counter-intuitive ’ and absurd to view a competence model such as the one he describes, as one of performance. He states (Chomsky, 1967b), ‘In fact, in implying that the speaker selects the general properties of sentence structure before selecting lexical items (before deciding what he is going to talk about), such a proposal seems not only without justification but entirely counter to whatever vague intuitions one may have about the processes that underlie production’ (p. 436). Chomsky thus regards language knowledge (competence) as a resource for use rather than as a process of use. It is information about our language which we tap in order to produce and understand sentences, and such information in and of itself is inadequate for such performance tasks.

Language knowledge (a system of rules) is regarded by Chomsky as actual knowledge that a person has. As such the content or the structure of this knowledge is a psychological characteristic of a person. It is the discovery of this underlying system of rules, this ‘mental reality underlying actual behavior’ (Chomsky, 1965) with which linguistic theory is concerned. The linguistic universals which Chomsky posits, deep structure, grammatical categories, etc., are held to be psychologically real since they specify characteristics of mind (Chomsky, 1968). Thus, while the linguist’s characterization of competence may be neutral in a sense with respect to use, it is evidently not neutral with respect to precisely how that knowledge is stored or organized in the person.

As an example of how a competence model may be utilized in performance, Chomsky (this volume) cites Katz and Postal. In their procedure for production, a semantic representation from the competence model is first selected, then a syntactic structure, then a phonetic representation. Such a set of selection rules would provide an account of a hypothetical performance model with respect to production. Another set of rules would be required to deal with the understanding or interpretation of sentences.

A problem arises, however, with regard to distinguishing the rules of ‘performance’ with those of ‘competence’. The basis for such a distinction is not immediately evident since both alleged types appear to qualify as language knowledge. For example, along with Katz (this volume), Chomsky regards those rules of the semantic component which are concerned with the disambiguation of sentences as belonging to competence. On the other hand, Weinreich (also this volume) views such rules as involved in the use of language. He says that we ‘ought to regard the automatic disambiguation of potential ambiguities as a matter of hearer performance ’. If the distinction between competence and performance is to be a viable one, more definitive criteria than those provided at present appear necessary.

In contrast to the empiricist notions of Osgood where meaning is conceived to be derived from behavior, Lenneberg holds a view of meaning that is essentially rationalistic. Words are viewed as tags for concept categories or categorization processes which are considered to be innate, i.e., the words of the lexicon are regarded as labels of innate categories. Such categories vary from species to species and the criteria or the nature of categorization, Lenneberg maintains, have to be determined empirically for each species.

In accord with his theme that language is species-specific, Lenneberg contends that there is a biologically based capacity for naming that is specific to man. He claims in the paper that it is not possible for an animal to do the ‘ name-specific stimulus generalization’ that every child does automatically, i.e., to regard some words as class names, and not specific object names. Lenneberg says: ‘ The hound who has learned to point to the tree, the gate, the house in the trainer’s yard will perform quite erratically when given the same command with respect to similar but physically different objects, in an unfamiliar environment.’ With respect to this claim the reader may wonder about the following case. Many dogs learn to respond to such verbal commands as ‘ Forward ’, ‘ Left ’, ‘ Right ’, ‘ Sit ’. Given the command ‘ Forward ’, a seeing-eye dog, for example, will go forward under a variety of environmental conditions, e.g., in a house, in a yard, in a street, or on a bus. The question is whether such a case would qualify as an instance of ‘name-specific stimulus generalization’. Unfortunately, Lenneberg offers but a brief sketch of his ideas6 before passing on to present a series of interesting and valuable empirical studies involving various aspects of relating words and objects with respect to physical dimensions.

The paper by Miller provides a very useful survey of various empirical methods which have been used in the study of meaning. While reading this review it should be borne in mind that the psychologist’s early venture into meaning was dominated, in the main, by the hope that meaning would provide a basis of differentiation among words, and thus account for how words became associated to form sentences. Measurement scales were constructed on the basis of such alleged semantic dimensions as: the number of associations given to a word within a unit of time, amount of salivation, intensity of galvanic skin response, or degree of favorability. The obvious inadequacy of any approach where but a single dimension of meaning is assumed to differentiate all words was recognized by many theorists, particularly Osgood and Deese. Osgood tried to remedy the situation with his multi-dimensional technique, the Semantic Differential; Deese with his structural description of association. Unfortunately no theorist who has been involved in the measurement of meaning has been able to isolate experimentally all of those varied aspects of meaning necessary for a relatively complete solution to semantic problems like those concerned with the formation of phrases and sentences and others considered in this volume.7

Of particular importance in the Miller paper is the presentation of a new method which Miller and his colleagues have developed. This method uses word classification as a discovery procedure through which elements of meaning (‘semantic markers ’) may be identified. The words to be classified are typed on cards and subjects are asked to sort them into piles on the basis of ‘similarity and meaning ’. The data then are tabulated in a matrix form on the basis of co-occurrence pairs so that an analysis which yields semantic clusters may be made. The method produces rather credible results as a glance at the Miller figure in the paper shows.

Since the technique yields a hierarchical arrangement of semantic markers, Miller recognizes that it is applicable only to those lexical domains where semantic markers structure to form a hierarchy.8 Miller has noted that there are lexical domains such as kinship terms where the semantic features which characterize it are not structured in a hierarchical fashion. One assumption underlying the method is that lexical items which have been judged as ‘similar’ (by being classified together) have been done so on the same basis of meaning. Such an assumption is necessary since there would be little semantic value to the finding that a group of subjects judged certain items as ‘similar’ but that it was based on judgments involving different semantic dimensions.9

The paper of Bever and Rosenbaum is also concerned with the determination of semantic structures. However, their focus is not so much upon the methodological problem of discovering semantic structure as it is upon the explanatory value of such structures. They posit certain featural and lexical hierarchical structures so that they may provide an explanation for why it is that certain sentences are regarded as semantically appropriate while others are regarded as semantically deviant. With reference to the first type of hierarchy, the authors postulate that elements of meaning (semantic features) underlie lexical items, e.g., a lexical item such as ‘person’ is characterized by such features as + human and + animate. They hold that features are related to one another in a hierarchical fashion, e.g., + human always implies + animate. The relations obtaining between features is conceived to be one of class inclusion. The assignment of semantic features to lexical items in terms of contextual privilege of occurrence enables the authors to provide a theoretical basis according to which acceptable and deviant sentences may be distinguished.10

The postulation of a second type of hierarchy, that of lexical items (to be distinguished from hierarchies of features),11 also allows the authors to account for judgmental differences concerning the acceptability of sentences. The be and have (inalienable inclusion) lexical hierarchies provide especially valuable insights for semantic theory construction and thus deserve the close attention of the reader.12

In closing, it is worth noting that all of the papers discussed above, besides contributing to our understanding of certain semantic problems, also illustrate that the impact of Chomsky’s ideas has been profound upon psychologists working in the area of language. The number of notable psychologists who have abandoned behaviorist theory has risen now to the extent that one of the most viable counter-behaviorist forces since the advent of behaviorism has been created. While thus far it is mainly in the area of language that behaviorism has been put on the defensive, the distinct possibility remains that all areas of psychology will be revolutionized by Chomskyan ideas (especially those of a transformational generative nature). It is still too early to tell however. In this regard one is reminded of the impact which Gestalists have had upon psychology. Their anti-behavioristic notions failed to penetrate much beyond their own area of specialization, that of perception.

1 I would like to thank C. E. Osgood of the University of Illinois and Masanori Higa of the University of Hawaii for their many helpful suggestions.

2 A single-stage conditioning model may be diagrammed as follows:

UCS -> UCR

CS -> CR

where UCS is the unconditioned stimulus, an object; UCR is the unconditioned response to the unconditioned stimulus; CS is the conditioned stimulus, a word form; and CR is the unconditioned response. Two different single-stage models are possible here: (1) where UCR ≠ CR, i.e., both responses are identical; and (2) where UCR 4= CR, i.e., both responses are not identical. The model both Fodor and Osgood criticize is (1), which is a substitution notion.

3 For further discussion concerning the dispute see Osgood, Fodor and Berlyne, all (1966).

4 For other challenges to the sufficiency of the principle of association, see Lashley (1951), Bever, Fodor and Garrett (1968), McNeill (1968) and Asch (1969).

5 For further discussion on this topic see the papers by Harman (1967, 1969), Chomsky (1969), Schwartz (1969), Fodor (1969) and those in Lyons and Wales (1966).

6 For an interesting discussion related to a consideration of Lenneberg’s view that names with unique referents may be incorporated into discourse but are not considered part of the lexicon, see the papers (particularly that of Linsky) in the Reference section of Philosophy.

7 I do not wish to imply that units which have been experimentally isolated by various theorists are necessarily semantically irrelevant. The Evaluation factor isolated by Osgood’s Semantic Differential, for instance, is undoubtedly of great semantic significance.

8 The method is also inapplicable in those cases where the semantic markers composing a hierarchy must be cross-referenced. This restriction is necessitated by the fact that no lexical item can appear in a final cluster analysis more than once. For example, with reference to the Miller figure it does not appear possible to deal with lexical items that have both ‘social ’ and ‘ personal ’ characteristics, or both ‘ personal ’ and ‘ quantitative ’ characteristics, etc.

9 To illustrate this point, suppose that subjects have been given a set of kinship terms to classify, and among them are the items ‘daughter’ and ‘son’. Further, suppose that some of the subjects think of ‘generation’ as a meaningful feature and classify daughter and son together because they are of the same generation, while the other subjects think of ‘lineality ’ (relatedness by blood) as a meaningful feature and classify daughter and son together because they are of the same lineage. Since these data are collapsed together in the co-occurrence matrix, a distinction between such features of meaning as ‘generation’ and ‘ lineality ’ would not be maintained. The matrix of co-occurrence would merely indicate that daughter and son are ‘similar’ to one another. Furthermore, that daughter and son will not be regarded as ‘similar’ if a subject makes a classification on the basis of ‘ sex’ also raises a problem since judgments of ‘similar’ and ‘dissimilar’ are treated by Miller as mutually exclusive. That is to say, the method cannot show that daughter and son are similar in some respects (generation lineality) while at the same time dissimilar in others (sex).

10 For a detailed consideration of some of the methodological problems involved in such an approach see the Alston paper in the Philosophy section.

11 Dixon (in the Linguistics section) hypothesizes a distinction somewhat similar to that of Bever and Rosenbaum with his concepts of ‘nuclear’ and ‘non-nuclear’.

12 A question may be raised, however, with respect to the consistency with which postulated deviancy criteria have been applied to the various sets of sentences. For example, it seems odd that sentence (4 ei) ‘the ant has an arm’ is viewed as not deviant while one like (22 c) ‘a shotgun shoots bullets’ is viewed as deviant. According to the authors, (4 ei)‘the ant has an arm ’, is not deviant because it ‘ doesn’t happen to be true ’ but (4 eii), ‘ the arm has an ant ’, is deviant because it ‘ couldn’t possibly be true ’. While this deviancy criterion is applied to these sentences and some others, it is not clear if this same criterion is also utilized when other sets of sentences are considered, such as those which include items as (7), ‘ The sword shoots bullets ’, and (22 c)’ A shotgun shoots bullets ’. Both of these sentences are regarded as deviant, i.e., they ‘couldn’t possibly be true’. Yet it does seem possible that a sword or a shotgun could be constructed to fire bullets, i.e., that the sentences in question actually ‘do not happen to be true’. Further empirical validation may be in order here.

|

|

|

|

5 علامات تحذيرية قد تدل على "مشكل خطير" في الكبد

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

لحماية التراث الوطني.. العتبة العباسية تعلن عن ترميم أكثر من 200 وثيقة خلال عام 2024

|

|

|