Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension|

Read More

Date: 2023-04-14

Date: 2023-03-22

Date: 2024-08-20

|

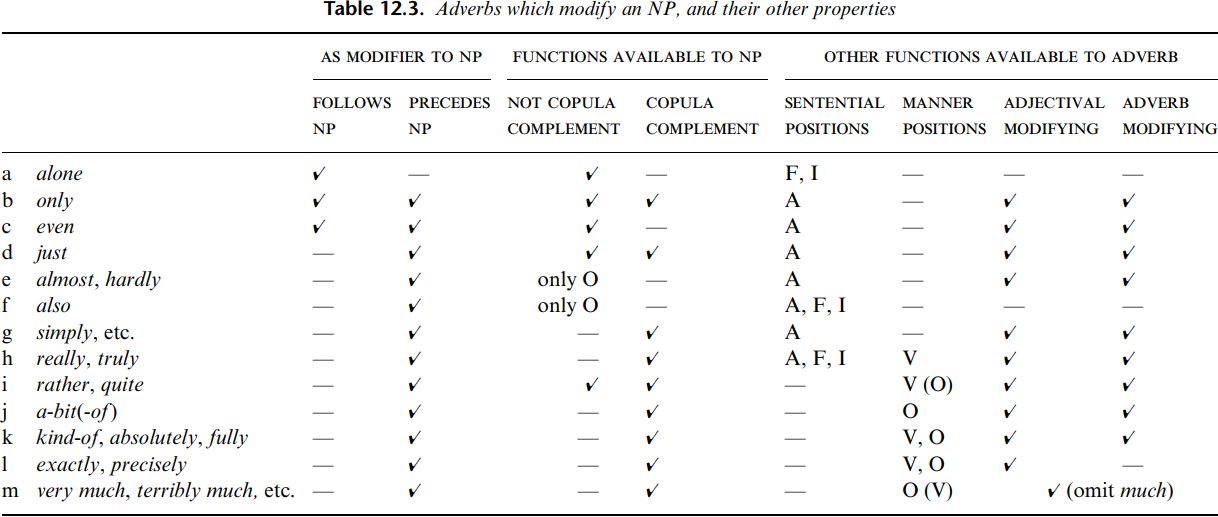

A relatively small number of adverbs may modify a full NP, coming at the very beginning (before any article or preposition) and/or at the very end. Some are restricted to NPs in copula complement function, some to NPs in non-copula-complement function, while some can be in NPs in any function.

It is important to distinguish between an adverb modifying an NP in copula complement (CC) function, and the same adverb with sentential function in A position. Consider:

(33) John is certainly an appropriate candidate

Now this could conceivably be parsed as John is [certainly an appropriate candidate] CC with the adverb as a modifier to the NP. Or certainly could be a sentential adverb in A position—that is, after the first word of the auxiliary if there is one, otherwise immediately before a verb other than copula be, or immediately after be. Which analysis is appropriate may be decided by adding an auxiliary. One can say:

(34a) John should certainly be an appropriate candidate

but scarcely:

(34b) *John should be [certainly an appropriate candidate]

That is, certainly functions as a sentential adverb in A position, as in (34a). It cannot modify an NP, as shown by the unacceptability of (34b). (Note that certainly an appropriate candidate also cannot occur in any other function in a clause; for example, one cannot say *[Certainly an appropriate candidate] applied for the position.) We infer that certainly must be in sentential function, at position A, in (33).

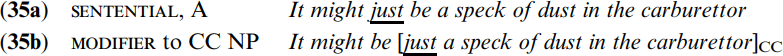

Other adverbs are unlike certainly in that they may have sentential function, at position A, and also modify an NP which is in copula complement function. Consider just in a copula clause with an auxiliary

There is a meaning difference. (35a) suggests that what was wrong with the car might be simply a speck of dust in the carburettor, rather than something more serious (such as a cracked cylinder), while (35b) suggests that it may be simply a speck of dust (not any bigger lump of dust) in the carburettor. Note that when there is no auxiliary, just a copula verb, both (35a) and (35b) reduce to:

(36) It is just a speck of dust in the carburettor

This is ambiguous between the two parsings (with distinct meanings)—one having just as sentential adverb in A position, and the other having just as modifier within the NP in copula complement function. In spoken language, the two senses of (36) may be distinguishable by stress going on just for the sentential meaning, as in (35a), and on dust in the modifier-to-CC sense, as in (35b). (Note that an NP modified by just may have other functions besides copula complement; for example, [Just a speck of dust in the carburettor] caused all that trouble.)

Quite often, an adverb modifier within an NP is a syntactic alternative (with very similar meaning) to the same adverb used in sentential function, in A position, with the NP stressed to show that it is in focus. Consider only; this can be a sentential adverb in position A, as in Children may only play soccer on the back lawn. This sentence can be accorded contrastive stress on either the object NP or the spatial NP:

(37a) Children may only play ’soccer on the back lawn

(37b) Children may only play soccer on the ’back lawn

An alternative way of saying (37a) is to place only at the beginning of the object NP, soccer, as in (38a); and an alternative way of expressing (37b) is to place only at the beginning of the spatial NP on the back lawn, as in (38b).

(38a) Children may play [only soccer] on the back lawn

(38b) Children may play soccer [only on the back lawn]

That is, placing only in an object NP or in a prepositional NP produces a similar effect to having only in A position with contrastive stress on the appropriate NP. Only may, of course, also modify a subject NP, as in [Only children] may play soccer on the back lawn, meaning that people other than children may not play soccer on the back lawn. There is then no equivalent construction with only as sentential adverb in A position. (’Children may only play soccer on the back lawn has a quite different meaning, perhaps implying that adults may play soccer on both back and front lawns).

We summarize properties of the main adverbs which may modify an NP. Commenting first on the columns, we find that alone, only and even may follow an NP while all items except for alone may precede. It will be seen that some adverbs are restricted to an NP in copula complement function while for others the NP may be in any function. In addition, an NP modified by alone or even may be in any function other than copula complement, while one modified by almost or hardly or also may only be in O function. (We can, however, have an adjective—as opposed to an NP— modified by any of these adverbs (except for alone) in copula complement function; for example, She is even beautiful, It is almost new.)

In the last two columns, most items may also directly modify an adjective or an adverb (those in set (m) then omit the much). Alone and also appear to have neither of these properties, while items in set (l) may scarcely modify an adverb. Forms in sets (h–m) also have manner function, in position V or O or both. Those in sets (a–h) also have sentential function—really, truly and also in positions A, F and I, alone in F and I, the remainder just in A. An adverb in sentential function, in A position, and the same adverb modifying an NP in O or oblique function, have very similar meanings. Even, just, almost and hardly, in sets (c–e), behave like only, set (b), in this property, as exemplified by (37)–(38).

The forms in (a–d) also occur as adjectives, with a difference of meaning from the corresponding adverb; for example, John is alone, This is the only way to go, The surface is even, The judge was just. Those in (g), and (l), and all in (m) except for very (much), are productively derived from an adjective by the addition of -ly.

Looking now at the rows, in turn:

(a) Alone may only follow (not precede) an NP, as in [The manager alone] is permitted to take an extra-long lunch break (meaning, no one but the manager is allowed this privilege). It has a slightly different meaning when used as a sentential adverb, as in John did the job alone, or Alone, John did the job, here indicating that there was no one with John, assisting him. When used as a sentential adverb, alone may be modified by all, as in John did the job all alone.

(b–c) Only and even can either precede or follow an NP which they modify, as in:

(39a) [Only initiated men] may view the sacred stones

(39b) [Initiated men only] may view the sacred stones

(40a) [Even John] couldn’t understand it

(40b) [John even] couldn’t understand it

The properties of only were discussed above; even differs just in that an NP it modifies may not be in copula complement function.

(d) There are two homonymous adverbs just, one with a time and the other with a non-time meaning. For example, Mary just smiled could mean (i) that she smiled a few moments ago; or (ii) that all she did was smile (for example, she did not also laugh). We deal here with the non-time adverb, which has very similar properties to only, save that it must precede (never follow) an NP it modifies, as in [Just a cheap hat] will suffice, or He is [just a boy]. (A further use of just is as a strengthener, similar to really and very, as in She was just beautiful.)

(e) This row relates to almost when not followed by all or every, and to hardly when not followed by any. These can function as sentential adverbs, in position A—as in (41a) and (42a)—or (with similar meaning) as pre-modifier to an NP, but probably only when that NP is in O function—as in (41b) and (42b). For example:

(41a) He had hardly written a word

(41b) He had written [hardly a word]

(42a) He had almost lost a thousand dollars at the Casino

(42b) He had lost [almost a thousand dollars] at the Casino

Almost all, almost every and hardly any can modify an NP in any function. They are best treated as complex adjectives (lacking sentential or manner or other adverbial functions).

(f) Also can modify an NP in O function, as in See [also the examples in the appendix], and can have sentential function, as in He might also have stolen the spoons. In addition, it functions as a clause linker.

(g) This set involves a number of de-adjectival forms such as simply, mainly, merely, mostly and chiefly. They can modify an NP in copula complement function, as in The proposal must have been [simply a mess], or function as sentential adverb in A position, as in He must simply have wanted to succeed.

(h) Really has a wide set of properties. It can be a sentential adverb in all three positions (for example, He had really not expected that, or He had not expected that, really or Really, he had not expected that). It can be an manner adverb in V position (He had not really enjoyed it) or a modifier to an NP in copula complement function (He could have been [really a hero]).

Whereas the sentential function of an adverb generally has similar meaning to its NP-modifying function, a manner function will typically have rather different semantic effect from an NP-modifying function. This applies to sets (h–m).

(i) An NP modified by rather or quite may be in any function; for example, [Rather an odd man] called on me today, I saw [quite a peculiar happening] and He is [rather a funny fellow]. When used as manner adverb, the meaning is rather different (if not quite different), as in I rather like it. (V position) or I like it rather (O position), indicating ‘to a certain degree’. These adverbs may also modify an adjective or another adverb, as in a rather odd fellow and quite stupidly.

(j–k) We find a-bit-of and kind-of as modifier to an NP in copula complement function, as in She’s [a-bit-of a joker] and He’s [kind-of a sissy]. They may also modify an adjective or an adverb, a-bit-of then omitting its of; as in kind-of jealous, a-bit cleverly. When in manner function, kind-of generally precedes the verb-plus-object but may follow it:

(43a) I had been [kind-of expecting it]

(43b) I had been [expecting it kind-of]

In contrast, a-bit (again omitting the of) can only be in O position, following verb-plus-object:

(44) I had been [enjoying it a-bit]

Absolutely and fully have very similar properties to kind-of.

(l) This set comprises a group of de-adjectival adverbs including exactly and precisely. They can modify an NP which is in copula complement function. For example, in That is [precisely the same thing], the adverb precisely means ‘identical to’. When used as a manner adverb—for example, He might have [precisely positioned it] or He might have [positioned it precisely]—the meaning is ‘in a precise (or accurate) way’.

(m) The final set comprises very much and many de-adjectival adverbs followed by much, such as terribly much, awfully much, dreadfully much, incredibly much (this is just a small sample of the possibilities). They may modify an NP in copula complement function, as in He is [very much the master of the house]. Retaining the much, they may function as manner adverb, typically in O position; for example, I [like it very much]. V position is possible with very much and terribly much (for example, I very much like it) but is less felicitous with some of the other items. Discarding the much, they may modify an adjective or an adverb, with intensifying meaning— very clear, very clearly, terribly clever, terribly cleverly.

Very is unusual in that it may also directly modify a noun, as in You are [the very man (for the job)]. In this function, very could be classed as an adjective, and has a meaning something like ‘appropriate’ (reminiscent of its original meaning when borrowed from French vrai, ‘true’).

The head of an NP may be followed by a prepositional phrase, typically referring to time or place; for example, the meeting on Monday or the bench in the garden. Alternatively, an NP head may be followed by a single-word time or spatial adverb; for example, the meeting yesterday or the bench outside/there.

There are other items which may modify an NP, with adverb-like function: for example, such and what (as in It was [such a sad story] and [What a clever girl] she is); they have no other adverbial functions. Enough can function as an adjective and may then either precede or follow the noun it modifies (enough money or money enough). It may follow an adjective or adverb with what appears to be adverbial function (He is [loyal enough], She spoke [clearly enough]). And we do also get enough plus of (rather like a-bit-of and kind-of) as adverbial modifier to a complete NP in copula complement function, as in He isn’t [enough of a man] (to defend the honor of his wife). Although we present the main features of adverbs which may modify an NP, it does not pretend to comprise an exhaustive account.

Adverbial modification may apply in a similar way for NPs in all functions (save copula complement). The NP may be in subject or object function, or it may be in a peripheral function, marked by a preposition. As pointed out, the same adverbial possibilities apply to an NP whether or not it is marked by a preposition—for example, I saw [exactly/precisely five owls] [exactly/precisely at ten o’clock]. And, as shown in (6b–c), an adverb may modify a complement clause just as it may an NP. Examples require semantic compatibility between adverb and complement clause, giving a fair range of possibilities. Even, which can precede or follow a noun, as in (45a–b), may also precede or follow a complement clause, as in (46a–b).

(45a) I regret [even my marriage]

(45b) I regret [my marriage even]

(46a) I regret [even that I married Mary]

(46b) I regret [that I married Mary even]

SPEED adverbs, such as quickly and slowly, cannot modify an NP in a core syntactic function. It might be thought that quickly and slowly modify prepositional NPs in a sentence like:

(47) John ran quickly around the garden and slowly along the road

Isn’t it the case that quickly around the garden and slowly along the road are each a constituent here? In fact they are not. Quickly and slowly are manner adverbs in position O (they could alternatively occur in position V, immediately before ran). The underlying sentence here is:

(47a) John [ran quickly] [around the garden] and John [ran slowly] [along the road]

The repeated words John ran are omitted, giving (47).

|

|

|

|

مخاطر عدم علاج ارتفاع ضغط الدم

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

اختراق جديد في علاج سرطان البروستات العدواني

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

مدرسة دار العلم.. صرح علميّ متميز في كربلاء لنشر علوم أهل البيت (عليهم السلام)

|

|

|