Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension|

Read More

Date: 2024-03-30

Date: 2024-02-14

Date: 2024-03-02

|

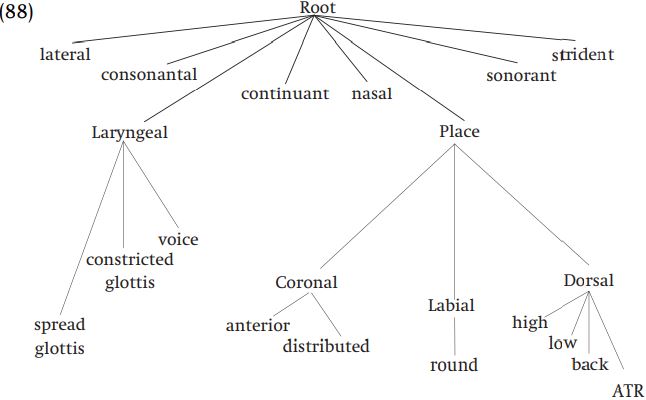

It was realized that all features are autonomous from all other features, and exhibit the kind of behavior which motivated the autosegmental treatment of tone. The question then arises as to exactly how features are arranged, and what they associate with, if the “segment” has had all of its features removed. The generally accepted theory of how features relate to each other is expressed in terms of a feature-tree such as (88). This tree – known as a feature geometry – expresses the idea that while all features express a degree of autonomy, certain subsets of the features form coherent phonological groups, as expressed by their being grouped together into constituents such as “Laryngeal” and “Place.”

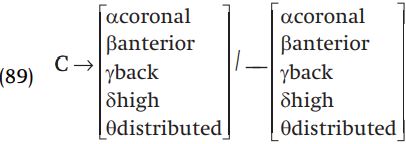

The organization of features into such a structure went hand-in-hand with the realization that the theory of rules could be constrained in very important ways. A long-standing problem in phonological theory was the question of how to express rules of multiple-feature assimilation. We have discussed rules of nasal place assimilation, and it was noted that such rules necessitate a special notation, the feature variable notation using α, β, γ, and so on. The notation makes some very bad predictions. First, notice that complete place assimilation requires specification of ten features in total.

This is less simple and, by the simplicity metric used in that theory, should occur less frequently than (90).

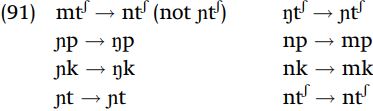

This prediction is totally wrong: (90) is not just uncommon, it is completely unattested. Were there to be such a rule that assimilates only the specification of coronal, we would expect to find sets of assimilations such as the following:

The fact that the feature-variable theory allows us to formulate such an unnatural process at all, and assigns a much higher probability of occurrence to such a rule, is a sign that something is wrong with the theory.

The theory says that there is only a minor difference in naturalness between (92) and (89), since the rules are the same except that (92) does not include assimilation of the feature [anterior].

There is a huge empirical difference between these rules: (89) is very common, (92) is unattested. Rule (92) is almost complete place assimilation, but [anterior] is not assimilated, so /np/, /ɲk/, and /mt/ become [mp], [ŋk], and [nt] as expected, but /ɲt/ and /ntʃ / do not assimilate (as they would under complete place assimilation); similarly, /ŋt ʃ / becomes [ɲt ʃ ] as expected (and as well attested), but /ŋp/ and /ŋt/ become [np] and [nt], since the underlying value [– anterior] from /ŋ/ would not be changed. Thus the inclusion of feature variables in the theory incorrectly predicts the possibility of many types of rules which do not exist in human language.

The variable-feature theory gives no special status to a rule where both occurrences of α occur on the same feature.

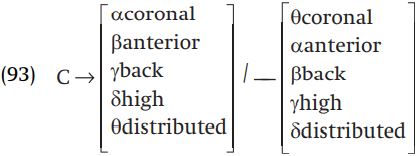

This rule describes an equally unnatural and unattested process whereby a consonant becomes [t] before [pj ], [p] before [q], and [pj ] before [k]. Rules such as (93) do not exist in human language, which indicates that the linear theory which uses this notation as a means of expressing assimilations makes poor predictions regarding the nature of phonological rules.

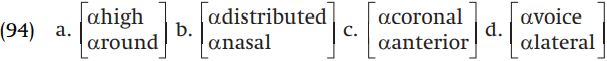

The variable notation allows us to refer to legions of unnatural classes by randomly linking two unrelated features with a single variable:

Class (a) applied to vowels refers to [y, u, e, ə, a]; (b) refers to [n̪, ɲ, p, ʈ, k] but excludes [m, ɳ, t̪, tʃ , ŋ]; (c) groups together [t, k] and excludes [p, tʃ ]; (d) refers to [l] plus voiceless consonants. Such groupings are not attested in any language.

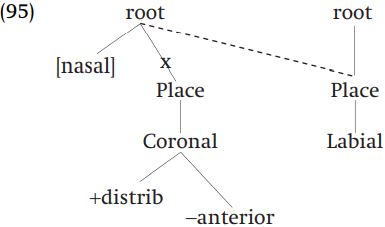

With the advent of a theory of feature geometry such as in (88), this problem disappeared. In that theory, the process of place assimilation is formulated not as the change of one feature value into another, but is expressed as the spreading of one node – in this case the Place node – at the expense of another Place node. Thus the change /ɲ/ ! [m] / _ [p] is seen as working as in (95):

Just as tone assimilation is the rightward or leftward expansion of the domain of a tone feature, this process of place assimilation is expansion of the domain of one set of place specifications, to the exclusion of another. When one Place node spreads and replaces the Place node of a neighboring segment, that means that all of the original place features are deleted, and the segment then comes to bear the entire set of place features that the neighboring segment has.

What the feature-variable notation was able to do was express multiple-feature assimilations, but given this alternative theory, multiple feature assimilations will be recast as spreading some node such as Place. The feature-variable notation can be entirely eliminated since its one useful function is expressed by different means. The theory of feature geometry enables a simple hypothesis regarding the form of phonological rules, which radically constrains the power of phonological theory. The hypothesis is that phonological rules can perform one simple operation (such as spreading, inserting or deletion) on a single element (a feature or organizing node in the feature tree).

The thrust of much work on the organization of phonological representations has been to show that this theory indeed predicts all and only the kinds of assimilations found in human languages (specific details of the structure of the feature tree have been refined so that we now know, for example, that the features which characterize vowel height form a node in the feature tree, as do the features for the front/back distinction in vowels). The nonlinear account of assimilations precludes the unnatural classes constructed by the expressions in (94), since the theory has no way to tie a specific value for a feature to the value of another feature. The theory does not allow a rule like (92), which involves spreading of only some features under the place node. The nature of a tree like (88) dictates that when a rule operates on a higher node, all nodes underneath it are affected equally. Unattested “assimilations” typified by (93) cannot be described at all in the feature-geometric theory, since in that theory the concept “assimilation” necessarily means “of the same unit,” which was not the case in the variable-feature theory.

The theory of features in (88) makes other claims, pertaining to how place of articulation is specified, which has some interesting consequences. In the linear model of features, every segment had a complete set of plus or minus values for all features at all levels. This is not the case with the theory of (88). In this theory, a well-formed consonant simply requires specification of one of the articulator nodes, Labial, Coronal or Dorsal. While a coronal consonant may have a specification under the Dorsal node for a secondary vocalic articulation such as palatalization or velarization, plain coronals will not have any specification for [back] or [high]; similarly, consonants have no specification for [round] or Labial unless they are labial consonants, or secondarily rounded. In other words, segments are specified in terms of positive, characteristic properties.

This has a significant implication in terms of natural classes. Whereas labials, coronals, and dorsals are natural classes in this theory (each has a common property) – and, in actual phonological processes, these segments do function as natural classes – the complements of these sets do not function as units in processes, and the theory in (88) provides no way to refer to the complement of those classes. Thus there is no natural class of [–coronal] segments ([p, k] excluding [t, tʃ ]) in this theory. Coronal is not seen as a binary feature in the theory, but is a single-valued or privative property, and thus there is no way to refer to the noncoronals since natural classes are defined in terms of properties which they share, not properties that they don’t share (just as one would not class rocks and insects together as a natural group, to the exclusion of flowers, by terming the group “the class of nonflowers”). Importantly, phonological rules do not ever seem to refer to the group [–coronal], even though the class [+coronal] is well attested as a phonological class. The model in (88) explains why we do not find languages referring to the set [p, k]. It also explains something that was unexplained in the earlier model: the consonantal groupings [p, t] versus [tʃ , k] are unattested in phonological rules. The earlier model predicted these classes, which are based on assignment of the feature [anterior]. In the model (88) the feature [anterior] is a dependent of the Coronal node, and thus labials and velars do not have a specification of [anterior], so there is no basis for grouping [p, t] or [tʃ , k] together.

|

|

|

|

5 علامات تحذيرية قد تدل على "مشكل خطير" في الكبد

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

لحماية التراث الوطني.. العتبة العباسية تعلن عن ترميم أكثر من 200 وثيقة خلال عام 2024

|

|

|