Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension|

Read More

Date: 15-1-2022

Date: 2023-10-27

Date: 14-1-2022

|

Theoretical challenges

Introduction

Up to this point, we’ve spent a lot of time looking at the way morphology works in languages – what kinds of morphemes there are, what to call them, how to analyze data, and so on. This is an important and necessary first step to becoming a morphologist, but there’s more to morphology than just being able to analyze data. When we study morphology, or indeed any of the other subfields of linguistics, we have a much larger goal in mind, which is to characterize and understand the human language faculty. Put a bit differently, our ultimate goal as linguists is to figure out the way in which language is encoded in the human mind. For morphologists, our specific goal is to figure out how the mental lexicon is encoded in the mind. Doing so requires us to model the mental representation of language, to make claims about exactly what morphological rules look like, and to propose hypotheses about what is possible in human languages and what is impossible.

A good hypothesis about language is one which is empirically testable: it should be clear what sort of data to look for that would disprove the hypothesis. To illustrate this, let’s look first at two examples of theoretical hypotheses that have been proposed by morphologists. I start with these two precisely because they make clear claims about what sorts of morphology we should expect to find in languages and because these claims have subsequently been disproven

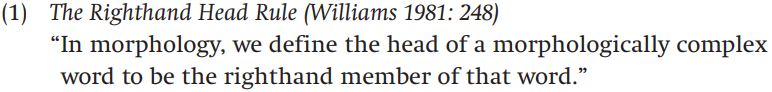

The first hypothesis we’ll look at is called the Righthand Head Rule:

You’ll recall that the head of a compound was the morpheme that determined the syntactic and semantic category of the compound. Clearly, in English, it’s the righthand element in the compound that’s the head (so sky blue is syntactically an adjective like blue and semantically a type of blue as well). More broadly, the head of a word is that morpheme that determines the category of the word, and in languages that have gender in nouns, or inflectional classes in nouns and verbs, the head determines the gender or class of the word as well. For example, in German, the suffix -heit attaches to adjectives to form nouns, specifically feminine nouns. Since -heit determines the category and gender of the derived noun, it is the head of the word. The Righthand Head Rule is a theoretical hypothesis that basically says that all compounds should be right-headed, and only suffixes (and not prefixes) can be the heads of words.

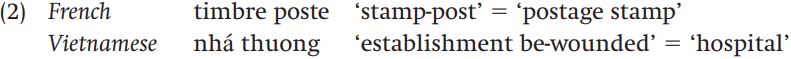

At first glance, this hypothesis is plausible enough when we look at English. Compounds are indeed right-headed, and for the most part in English it’s the suffix that determines the category of a complex word. However, the Righthand Head Rule can easily be disproven by looking at data from other languages. For example, we saw that both Vietnamese and French have left-headed compounds:

And it is not hard to find languages in which prefixes change the category of words and determine their gender or class. Even English has at least one prefix that changes category, and therefore would have to be recognized as the head of the derived word:

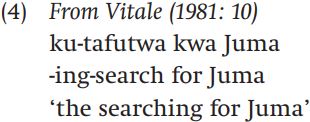

The prefix de- attaches to nouns and makes verbs. Similarly, Swahili has a prefix ku- that forms nouns from verbs:

Since this prefix determines the category of the derived word, we would have to consider it to be the head of the word. These examples show, then, that the Righthand Head Rule cannot be correct.

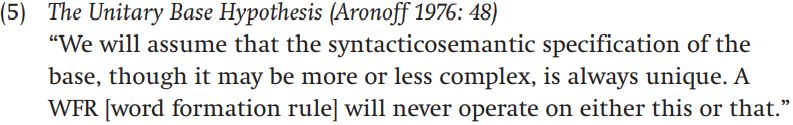

A second theoretical proposal that turns out not to be correct is the Unitary Base Hypothesis:

The Unitary Base Hypothesis in effect says that we should never expect to find in a language a morpheme that attaches to bases of two different categories, say adjective and noun, or noun and verb. We have seen, however, that there are many affixes that can attach to more than one base: -ize in English attaches to both adjectives (legalize) and nouns (unionize) to form verbs, and -er attaches to both verbs (writer) and nouns (villager) to form nouns.1 It seems that affixes sometimes (in fact frequently!) do attach to “either this or that.” The Unitary Base Hypothesis makes a clear claim about what we should expect to find in the languages of the world, but that is not in fact what we find.

Why start out a subject on theory with two incorrect hypotheses? What is important is that these hypotheses are testable: we know what sort of data to look for, and having looked for those data can determine that

These hypotheses cannot correctly characterize our theoretical model of the mental lexicon. Notice that I haven’t talked about proving hypotheses to be true. In fact, it is never possible to prove a scientific hypothesis to be true: since there will always be some linguistic data we have not yet looked at, there is always some chance that further study will prove a hypothesis to be false. We take a theoretical hypothesis to be sound, just as long as we have not yet found evidence against it.

Good hypotheses must therefore be testable, and we would like them to explain a wide range of data. But there is one more thing we would want of a good theoretical hypothesis: it must also be simple. Since generative linguists are ultimately concerned with the mental representation of language, part of their concern is to explain how children acquire knowledge of those mental representations so quickly and with such ease. We assume that the simpler our proposed mental representations, the easier it would be for children to acquire them, and therefore the more plausible they should be.

With this in mind, we can now go on to look at a number of other theoretical proposals for characterizing our mental representation of morphology that are less easy to dismiss. Keep in mind that we can look at only a few interesting points of morphological theory here; in the last three decades there has been a great deal written about morphological theory that we will not be able to cover. So what I hope to do here is to give you a taste of theory and to whet your appetite for further study.

|

|

|

|

"إنقاص الوزن".. مشروب تقليدي قد يتفوق على حقن "أوزيمبيك"

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

الصين تحقق اختراقا بطائرة مسيرة مزودة بالذكاء الاصطناعي

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

العتبة العباسية المقدسة تطلق النسخة الحادية عشرة من مسابقة الجود العالمية للقصيدة العمودية

|

|

|