النبات

مواضيع عامة في علم النبات

الجذور - السيقان - الأوراق

النباتات الوعائية واللاوعائية

البذور (مغطاة البذور - عاريات البذور)

الطحالب

النباتات الطبية

الحيوان

مواضيع عامة في علم الحيوان

علم التشريح

التنوع الإحيائي

البايلوجيا الخلوية

الأحياء المجهرية

البكتيريا

الفطريات

الطفيليات

الفايروسات

علم الأمراض

الاورام

الامراض الوراثية

الامراض المناعية

الامراض المدارية

اضطرابات الدورة الدموية

مواضيع عامة في علم الامراض

الحشرات

التقانة الإحيائية

مواضيع عامة في التقانة الإحيائية

التقنية الحيوية المكروبية

التقنية الحيوية والميكروبات

الفعاليات الحيوية

وراثة الاحياء المجهرية

تصنيف الاحياء المجهرية

الاحياء المجهرية في الطبيعة

أيض الاجهاد

التقنية الحيوية والبيئة

التقنية الحيوية والطب

التقنية الحيوية والزراعة

التقنية الحيوية والصناعة

التقنية الحيوية والطاقة

البحار والطحالب الصغيرة

عزل البروتين

هندسة الجينات

التقنية الحياتية النانوية

مفاهيم التقنية الحيوية النانوية

التراكيب النانوية والمجاهر المستخدمة في رؤيتها

تصنيع وتخليق المواد النانوية

تطبيقات التقنية النانوية والحيوية النانوية

الرقائق والمتحسسات الحيوية

المصفوفات المجهرية وحاسوب الدنا

اللقاحات

البيئة والتلوث

علم الأجنة

اعضاء التكاثر وتشكل الاعراس

الاخصاب

التشطر

العصيبة وتشكل الجسيدات

تشكل اللواحق الجنينية

تكون المعيدة وظهور الطبقات الجنينية

مقدمة لعلم الاجنة

الأحياء الجزيئي

مواضيع عامة في الاحياء الجزيئي

علم وظائف الأعضاء

الغدد

مواضيع عامة في الغدد

الغدد الصم و هرموناتها

الجسم تحت السريري

الغدة النخامية

الغدة الكظرية

الغدة التناسلية

الغدة الدرقية والجار الدرقية

الغدة البنكرياسية

الغدة الصنوبرية

مواضيع عامة في علم وظائف الاعضاء

الخلية الحيوانية

الجهاز العصبي

أعضاء الحس

الجهاز العضلي

السوائل الجسمية

الجهاز الدوري والليمف

الجهاز التنفسي

الجهاز الهضمي

الجهاز البولي

المضادات الميكروبية

مواضيع عامة في المضادات الميكروبية

مضادات البكتيريا

مضادات الفطريات

مضادات الطفيليات

مضادات الفايروسات

علم الخلية

الوراثة

الأحياء العامة

المناعة

التحليلات المرضية

الكيمياء الحيوية

مواضيع متنوعة أخرى

الانزيمات

The diaphragm

المؤلف:

Harold Ellis,Vishy Mahadevan

المصدر:

Clinical Anatomy Applied Anatomy for Students and Junior Doctors

الجزء والصفحة:

13th Edition , p14-19

2025-02-13

1515

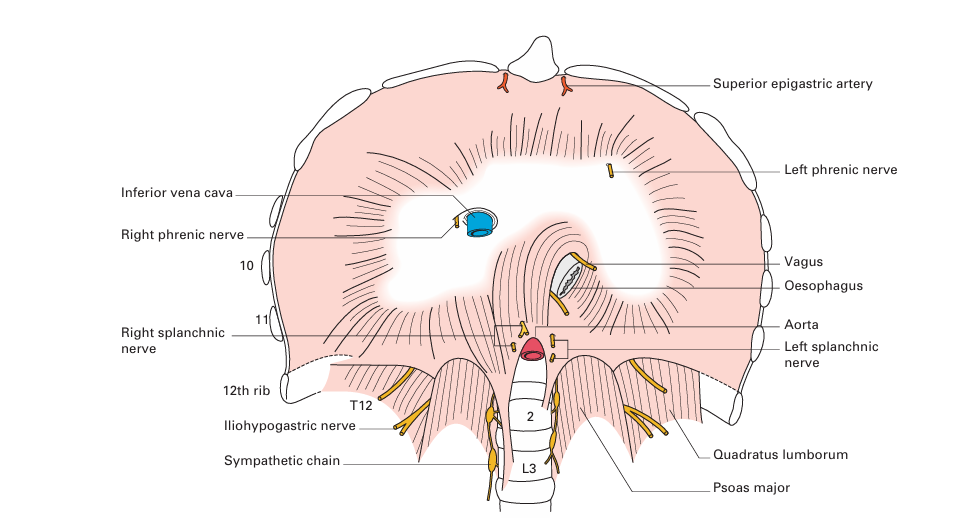

The diaphragm is the dome-shaped septum dividing the thoracic from the abdominal cavity. It comprises two portions: a peripheral muscular part that arises from the margins of the thoracic outlet and a centrally placed aponeurosis (Fig. 1).

Fig1. The diaphragm – inferior aspect. The three major orifices, from above downwards, transmit the inferior vena cava, oesophagus and aorta.

The muscular fibres are arranged in three parts.

1- A vertebral part from the crura and from the arcuate ligaments. The right crus arises from the front of the bodies of the upper three lumbar vertebrae and intervertebral discs; the left crus is attached to only the first two vertebrae. The arcuate ligaments are a series of fibrous arches, the medial being a thickening of the fascia covering psoas major and the lateral of the fascia overlying quadratus lumborum. The fibrous medial borders of the two crura form a median arcuate ligament over the front of the aorta.

2- A costal part is attached to the inner aspect of the lower six ribs and costal cartilages.

3- A sternal portion consists of two small slips from the deep surface of the xiphisternum.

The central tendon, into which the muscular fibres are inserted, is trefoil in shape and is partially fused with the undersurface of the pericardium.

The diaphragm receives its entire motor supply from the phrenic nerve (C3, C4, C5), whose long course from the neck follows the embryological migration of the muscle of the diaphragm from the cervical region (see below). Injury or operative division of this nerve results in paralysis and elevation of the corresponding half of the diaphragm.

Radiographically, paralysis of the diaphragm is recognized by its elevation and paradoxical movement; instead of descending on inspiration, it is forced upwards by pressure from the abdominal viscera.

The sensory nerve fibres from the central part of the diaphragm also run in the phrenic nerve; hence, irritation of the diaphragmatic pleura (in pleurisy) or of the peritoneum on the undersurface of the diaphragm by subphrenic collections of pus or blood produces referred pain in the corresponding cutaneous area, the shoulder-tip.

The peripheral part of the diaphragm, including the crura, receives sensory fibres from the lower intercostal nerves.

Openings in the diaphragm

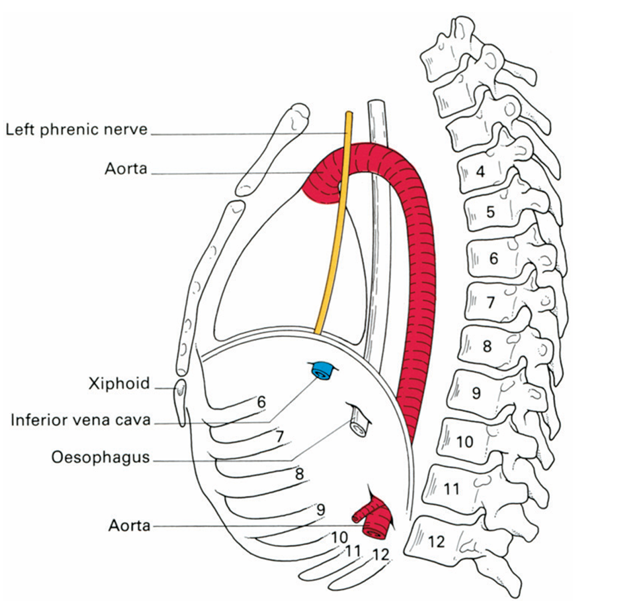

The three main openings in the diaphragm (Figs 1, 2) are:

1- the aortic (at the level of T12), which transmits the abdominal aorta, the thoracic duct and often the azygos vein;

2- the oesophageal (T10), which is situated between the muscular fibres of the right crus of the diaphragm and transmits, in addition to the oesophagus, branches of the left gastric artery and vein and the two vagi;

3- the opening for the inferior vena cava (T8), which is placed in the central tendon and also transmits the right phrenic nerve. In addition to these structures, the greater and lesser splanchnic nerves pierce the crura and the sympathetic chain passes behind the diaphragm deep to the medial arcuate ligament.

.fig2. Schematic lateral view of the diaphragm to show the levels at which it is pierced by major structures.

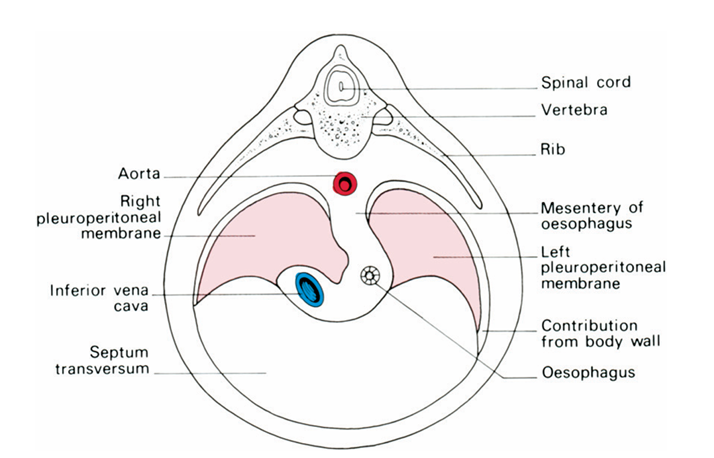

The development of the diaphragm and the anatomy of diaphragmatic herniae

The diaphragm is formed (Fig. 3) by fusion in the embryo of:

1- the septum transversum (forming the central tendon);

2- the dorsal oesophageal mesentery;

3- a peripheral rim derived from the body wall;

4- the pleuroperitoneal membranes, which close the fetal communication between the pleural and peritoneal cavities.

fig3. The development of the diaphragm, showing the four elements contributing to the diaphragm – (1) the septum transversum, (2) the dorsal mesentery of the oesophagus, (3) the body wall and (4) the pleuroperitoneal membrane.

The septum transversum is the mesoderm which, in early development, lies in front of the head end of the embryo. With the folding off of the head, this mesodermal mass is carried ventrally and caudally, to lie in its definitive position at the anterior part of the diaphragm. During this migration, the cervical myotomes and nerves contribute muscle and nerve supply respectively, thus accounting for the long course of the phrenic nerve (C3, C4 and C5) from the neck to the diaphragm.

With such a complex embryological story, one may be surprised to know that congenital abnormalities of the diaphragm are unusual.

However, a number of defects can occur, giving rise to a variety of congenital herniae through the diaphragm. These may be:

1- through the foramen of Morgagni – anteriorly between the xiphoid and costal origins;

2- through the foramen of Bochdalek – the pleuroperitoneal canal – lying posteriorly;

3- through a deficiency of the whole central tendon (occasionally such a hernia may be traumatic in origin);

4- through a congenitally large oesophageal hiatus.

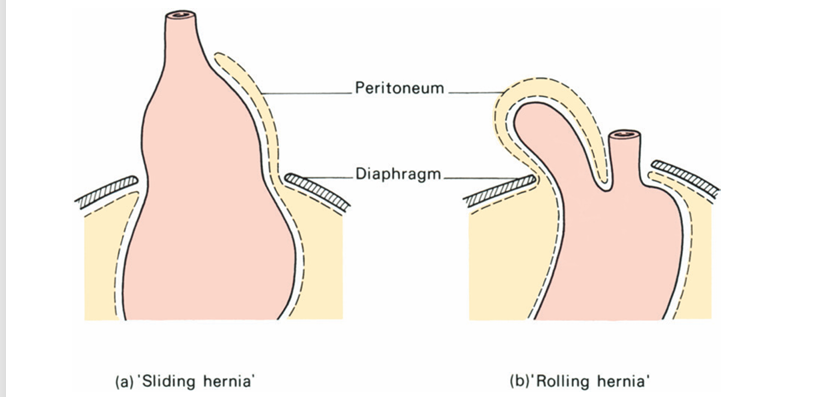

Far more common are the acquired hiatus herniae (subdivided into sliding and rolling herniae). These are found in patients usually of middle age in whom weakening and widening of the oesophageal hiatus has occurred (Fig. 4).

fig 4. (a) A sliding hiatus hernia. (b) A rolling hiatus hernia.

In the sliding hernia the upper stomach and lower oesophagus slide upwards into the chest through the lax hiatus when the patient lies down or bends over; the competence of the cardia is often disturbed and peptic juice can therefore regurgitate into the gullet in lying down or bending over. This may be followed by oesophagitis with consequent heartburn, bleeding and, eventually, stricture formation.

In the rolling hernia (which is far less common) the cardia remains in its normal position and the cardio-oesophageal junction is intact, but the fundus of the stomach rolls up through the hiatus in front of the oesophagus; hence, the alternative term of para-oesophageal hernia. In such a case there may be epigastric discomfort, flatulence and even dysphagia, but no regurgitation because the cardiac mechanism is undisturbed.

The movements of respiration

During inspiration the movements of the chest wall and diaphragm result in an increase in all diameters of the thorax. This, in turn, brings about an increase in the negative intrapleural pressure and an expansion of the lung tissue. Conversely, in expiration the relaxation of the respiratory muscles and the elastic recoil of the lung reduce the thoracic capacity and force air out of the lungs.

Quiet inspiration is brought about almost entirely by active contraction of the diaphragm with very little chest movement. Confirm this on yourself; your hands on your chest will show minimal movement as you breathe quietly. As respiratory movement grows deeper, the contraction of the intercostal muscles raises the ribs. The first rib remains relatively stationary, ribs 2–6 principally increase the anteroposterior diameter of the thorax (the pump handle movement), while the corresponding action of the lower ribs is to increase the transverse diameter of the thoracic cage (the bucket handle movement). Again, confirm this on your own chest during deep inspiration. In progressively deeper inspiration, more and more of the diaphragmatic musculature is called into play. On radiographic screening of the chest, the diaphragm will be seen to move approximately 1 in (2.5 cm) in quiet inspiration and up to 2.5–4 in (6–10 cm) on deep inspiration.

Normal quiet expiration is brought about by elastic recoil of the elevated ribs and passive relaxation of the contracted diaphragm. In deeper expiration, the abdominal muscles have an important part to play – they contract vigorously, compress the abdominal viscera, raise the intra-abdominal pressure and force the relaxed diaphragm upwards. Indeed, diaphragmatic movement accounts for approximately 65% of air exchange whereas chest movement accounts for the remaining 35%.

In deep and forced inspiration, additional ‘accessory muscles of respiration’ are called into play. These are the muscles attached to the thorax that are normally used in movements of the arms and the head. Watch an athlete at the end of a run, or observe a severely dyspnoeic patient – he grips his thighs or the table to keep his arms still, holds his head stiffly and uses pectoralis major, serratus anterior, latissimus dorsi and sternocleidomastoid to act ‘from insertions to origins’ to increase the capacity of the thorax. Observe also that the woman in advanced pregnancy has her diaphragm elevated and splinted by the enlarged fetus – she relies on chest movements in respiration even when she is resting quietly as she sits in the antenatal clinic.

الاكثر قراءة في علم التشريح

الاكثر قراءة في علم التشريح

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)