تاريخ الرياضيات

تاريخ الرياضيات

الرياضيات في الحضارات المختلفة

الرياضيات في الحضارات المختلفة

الرياضيات المتقطعة

الرياضيات المتقطعة

الجبر

الجبر

الهندسة

الهندسة

المعادلات التفاضلية و التكاملية

المعادلات التفاضلية و التكاملية

التحليل

التحليل

علماء الرياضيات

علماء الرياضيات |

Read More

Date: 22-10-2017

Date: 3-11-2017

Date: 12-10-2017

|

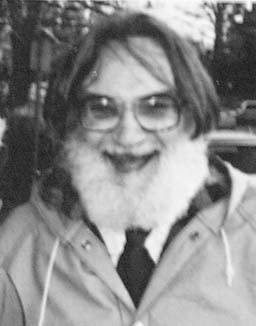

Died: 9 March 1993 in Bloomington, Indiana, USA

Max Zorn was born in Krefeld in western Germany, about 20 km northwest of Dusseldorf. He attended Hamburg University where he studied under Artin. Hamburg was Artin's first academic appointment and Zorn became his second doctoral student. He received his Ph.D. from Hamburg in April 1930 for a thesis on alternative algebras. We shall explain below what an alternative algebra is and describe some of the mathematical contributions which Zorn made at this time. At this stage, however, we should comment that his achievements were considered outstanding by the University of Hamburg and he was awarded a university prize. He was appointed as an assistant at Halle but he did not have the opportunity to work there for long since, in 1933, he was forced to leave Germany because of the Nazi policies. He was not, however, Jewish.

Zorn emigrated to the United States and was appointed a Sterling Fellow at Yale University. He worked there from 1934 to 1936 and it was during this period that he proposed "Zorn's Lemma" for which he is best known. We describe below the form in which Zorn originally stated this result. Following his years at Yale, he moved to the University of California at Los Angeles where he remained until 1946. During this time Herstein was one of his doctoral students. He left the University of California to become professor at Indiana University, holding this position from 1946 until he retired in 1971.

Since Zorn is best known for "Zorn's Lemma" it is perhaps appropriate that we should begin a discussion of his mathematical achievements by considering this contribution. Of course Zorn did not call his result "Zorn's Lemma", rather it was given by him as a "maximum principle" in a short paper entitled A remark on method in transfinite algebra which he published in the Bulletin of the American Mathematical Society in 1935. Perhaps in passing we should note that the name "Zorn's Lemma" was due to John Tukey. Zorn's aim in this paper was to study field theory and in particular to improve on the method used for obtaining results in the subject. Methods used up to that time had depended heavily on the well-ordering principle which Zermelo had proposed in 1904, namely that every set can be well-ordered. What Zorn proposed in the 1935 paper was to develop field theory from the standard axioms of set theory, together with his maximum principle rather than Zermelo's well-ordering principle.

The form in which Zorn stated his maximum principle was as follows. The principle involved chains of sets. A chain is a collection of sets with the property that for any two sets in the chain, one of the two sets is a subset of the other. Zorn defined a collection of sets to be closed if the union of every chain is in the collection. His maximum principle asserted that if a collection of sets is closed, then it must contain a maximal member, that is a set which is not a proper subset of some other in the collection. The paper then indicated how the maximum principle could be used to prove the standard field theory results.

Today we know that the Axiom of Choice, the well-ordering principle, and Zorn's Lemma (the name now given to Zorn's maximum principle by Tukey and now the standard name) are equivalent. Did Zorn know this when he wrote his 1935 paper? Well at the end of the 1935 paper he did say that these three are all equivalent and promised a proof in a future paper. Was Zorn's idea entirely new? Well similar maximum principles had been proposed earlier in different contexts by several mathematicians, for example Hausdorff, Kuratowski and Brouwer. Paul Campbell examines this question in [1] and:-

... investigates the claim that "Zorn's Lemma" is not named after its first discoverer, by carefully tracing the origins of several related maximal principles and of the name "Zorn's Lemma".

Zorn made other contributions to set theory, such as his 1944 paper Idempotency of infinite cardinals in which he proved that an infinite cardinal number is equal to its square. His proof uses his maximum principle rather than using ordinal numbers as had been done in previous proofs of the result.

In addition to his well known work in infinite set theory, Zorn worked on topology and algebra. As we mentioned above his doctoral thesis was on alternative algebras. These are algebras in which (xy)z - x(yz) is an alternating function in the sense that it is zero whenever any two of x, y, z are equal or, put another way, any two dimensional subalgebra is associative. Zorn went on to publish four papers on alternative algebras. He proved the uniqueness of the Cayley numbers (or octonians) in 1933 by showing that it was the only alternative, quadratic, real nonassociative algebra without zero divisors. He studied the structure of semisimple alternative rings in 1932, proving that such a ring is a direct sum of simple alternative algebras which he classified. In Alternative rings and related questions I: existence of the radical published in 1941 Zorn considered the theory of the radical of an alternative ring. He also published results on algebras which were fundamental in the study of algebraic number fields.

We have looked briefly at Zorn's contributions to algebra and to set theory. Let us now take a brief look at his contributions to analysis. In 1945 he published the paper Characterization of analytic functions in Banach space in the Annals of Mathematics. We quote from the introduction to that paper since it both states the type of problems that Zorn was examining very clearly, and also because it illustrates his clear style of writing mathematics:-

The concept of analyticity may be extended in various ways to functions from one complex Banach space to another. We may ask that the function be differentiable on one-dimensional (complex) subspaces; here one is led to the theory of the Gâteaux differential. Or we may prescribe a seemingly much more powerful condition, namely, that the function possesses a development into (abstract) power series about each point of the domain of definition. Here the Fréchet differential plays a decisive role.

The characterization theorem which we are going to derive will serve to show that the functions which fall under the first definition but not under the second are, from a certain point of view, to be considered as freaks, counter examples rather than examples. They are similar in character to, say, additive functions of a real variable which are not linear. For it turns out that only a very weak continuity property has to be added to the existence of the Gâteaux differential in order to ensure the existence of the power series development called for by the second definition.

After 1947 Zorn stopped publishing mathematical papers. This does not mean that he gave up mathematics. As Haile said at the Memorial Symposium held for Zorn at Indiana University in June 1993 (see [3]):-

... Max's published work, as significant and substantial as it is, is not what we will remember him by. It is rather Max's life-long dedication to mathematics and his apparently endless curiosity about mathematical ideas that we remember and from which we draw inspiration.

Ewing writes [2]:-

In his retirement Max Zorn became an essential part of the department. He came to the office every day, seven days a week. He was at tea, at seminars, and at colloquia. His questions were often penetrating and sometimes enigmatic. Outside speakers were usually charmed by Max and his passion for mathematics.

Halmos [4] also describes the colloquia:-

I don't remember any colloquium at which he didn't ask a question afterwards (and sometimes during) - a relevant question, a pertinent question, a sharp question. His questions showed that he understood the subject, understood the talk, and was ready to understand and remember the answers.

Returning to Ewing [2]:-

In recent years Max became fascinated by the Riemann Hypothesis and possible proofs using techniques from functional analysis. He read and studied and talked about mathematics nearly every day of his life. From time to time he published a slim newsletter, the Piccayune Sentinel, devoted to cryptic remarks about mathematics and mathematicians. He was a gentle man with a sharp wit who, during nearly half a century, inspired and charmed his colleagues at Indiana University.

Perhaps the reference to the Piccayune Sentinel deserves comment. Zorn did spell this with two c's but it is named after the newspaper the New Orleans Picayune. Halmos in [4] gives more details:-

I don't know just when he started it; the first issue that I have a copy of is dated November 1950. It was a one-sheet affair that Max called the world's smallest newspaper and that he gave to a few friends (usually by putting copies into his colleagues' mailboxes, and rarely, for distant friends, by mailing them). ... The contents of the Piccayune Sentinel were of the same kind as Max himself and his postcards (and as unpredictable and as confusion-inducing) ...

Max Zorn married Alice Schlottau and they had one son Jens and one daughter Liz.

Articles:

|

|

|

|

لخفض ضغط الدم.. دراسة تحدد "تمارين مهمة"

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

طال انتظارها.. ميزة جديدة من "واتساب" تعزز الخصوصية

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

عوائل الشهداء: العتبة العباسية المقدسة سبّاقة في استذكار شهداء العراق عبر فعالياتها وأنشطتها المختلفة

|

|

|