Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension|

Read More

Date: 4-3-2022

Date: 2024-09-17

Date: 2024-09-06

|

The existence of the pyramid rules enables you to start with an idea anywhere in the pyramid and discover all the others. Essentially, though, you will either be working from the top down or from the bottom up. I have tried to tell you exactly what to do in a general way, but the possibilities are endless, so that questions are inevitable. Following are the answers to some of the most commonly asked questions from beginning users of the pyramid.

1. Always try top down first. The minute you express an idea in writing, it tends to take on the most extraordinary beauty. It appears to have been chiseled in gold, making you reluctant to revise it if necessary. Consequently, try not to begin by just dictating the whole document "to get it all down," on the assumption that you can figure out the structure more easily afterwards. The chances are you'll love it once you see it typed, no matter how disjointed the thinking really is.

2. Use the Situation as the starting point for thinking through the introduction. Once you know what you want to say in the bulk of the introduction-Situation, Complication, Question, and Answer-you can place these elements in any order you like as you write, depending on the effect you want to create. The order you choose affects the tone of the document, and you will no doubt want to vary it for different kinds of documents. Nevertheless, begin your thinking with the Situation, since you're more likely to be able to identify the correct Complication and Question following that order.

3. Don't omit to think through the introduction. Very often you'll sit down to write and have the main point fully stated in your head, so that the Question that triggered it is obvious. The tendency then is to jump directly down to the Key Line and begin answering the New Question raised by the statement of the main point. Don't be tempted. In most cases, you will find that you end up structuring information that properly belongs in the Situation or Complication, and therefore forcing yourself into a complicated and unwieldy deductive argument. Sort out the introductory information first, leaving yourself free to concentrate solely on ideas at the lower levels.

4. Always put historical chronology in the introduction. You cannot tell the reader "what happened" in the body of the document, in an effort to let him know the facts. The body can contain only ideas (i.e., statements that raise a question in the reader's mind because they present hint with new thinking) and ideas can relate to each other only logically. This means that you can talk about events only if you are spelling out cause-and-effect relationships, since these had to be discovered through analysis. Simple historical occurrences do not exist as the result of logical thought, and therefore cannot be included as ideas.

5. Limit the introduction to what the reader will agree is true. The introduction is meant to tell the reader only what he already knows. Sometimes, of course, you won't know whether he actually knows something; at other times, you may be certain that indeed he does not know it. If the point being made can be easily checked by an objective observer and deemed to be a true statement, then your reader can be presumed to "know" it in the sense that he will not question its truth.

At the same time, be careful not to include in the introduction anything that the reader does not know. Including information that he does not know will cause you to distort his Question. And of course, conversely; do not include in the pyramid structure any information that the reader does know. Using information he does know to answer a lower level question implies that you have left important in information out of the introduction, which if known would lead the reader to ask a different Question.

6. Given a choice, use induction rather than deduction to formulate the argument on the Key Line level. This point is discussed more fully in, Deduction and Induction: The Difference. You will find that inductive reasoning at the Key Line level is easier for a reader to absorb than deductive because it requires less effort to comprehend. The tendency is to want to present your thinking in the order in which you developed it, which is generally a deductive process. But that you developed your ideas in that order does not mean you need to present them that way. In most cases you can present deductively developed ideas in an inductive form.

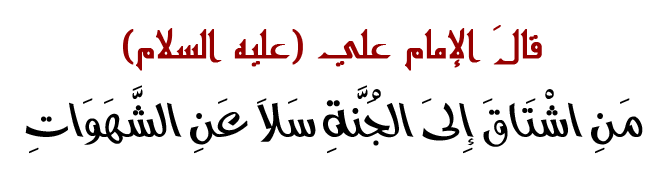

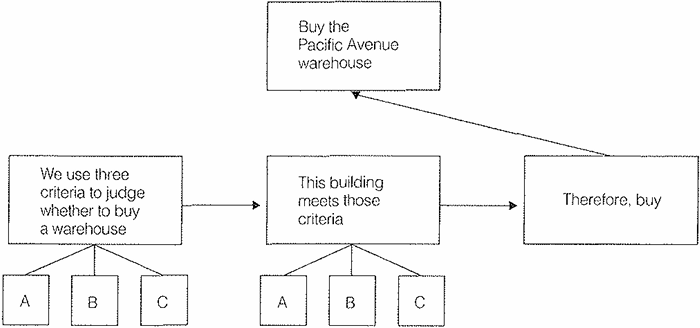

Suppose you want to tell someone to buy a warehouse, and you support the recommendation with the following deductive argument.

Here the third point does not raise a question. And assuming your order of writing is to state first the top point and then the Key Line points, you do not need the third point to make the message clear. This is an overstructured argument, and signals that the inductive form would more efficiently communicate your message.

proof device of this sort is the lure of an unfinished story. For example, suppose I say to you:

“Two Irishmen met on a bridge at midnight in a strange city . . .”

I have your interest actively engaged for the moment, despite whatever else you may have been thinking about before you read the words. I have riveted your mind to a specific time and place, and I can effectively control where it goes by focusing it on what the two Irishmen said or did, releasing it only when I give the punch line.

That's what you want to do in an introduction. You want to build on the reader's interest in the subject by telling him a story about it. Every good story has a begin ning, a middle, and an end. That is, it establishes a situation, introduces a complication, and offers a resolution. The resolution will always be your major point, since you always write either to resolve a problem or to answer a question already in the reader's wind.

But the story has also got to be a "good" story for the reader. If you have any children you know that the best stories in the whole world are the ones they already know. Consequently if you want to tell the reader a really good story you tell him one he already knows or could reasonably be expected to know if he's at all well informed.

Psychologically speaking, of course, this approach enables you to tell him things with which you know he will agree, prior to your telling him things with which he may disagree. Easy reading of agreeable points is apt to render him more receptive to your ideas than confused plodding through a morass of detail.

|

|

|

|

التوتر والسرطان.. علماء يحذرون من "صلة خطيرة"

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

مرآة السيارة: مدى دقة عكسها للصورة الصحيحة

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

نحو شراكة وطنية متكاملة.. الأمين العام للعتبة الحسينية يبحث مع وكيل وزارة الخارجية آفاق التعاون المؤسسي

|

|

|