Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension|

Read More

Date: 2023-08-31

Date: 2023-09-22

Date: 2023-11-01

|

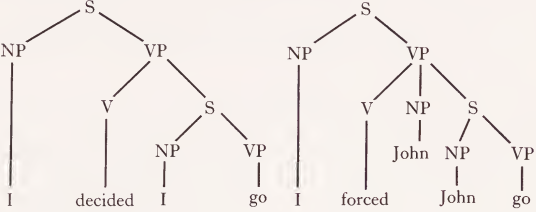

Let us first return in somewhat more detail to infinitive constructions, examining first the derivation of infinitives in general and then of the class of infinitive constructions which we mentioned as being characteristic of non-factive predicates. Basic to our treatment of infinitives is the assumption that non-finite verb forms in all languages are the basic, unmarked forms. Finite verbs, then, are always the result of person and number agreement between subject and verb, and non-finite verbs, in particular, infinitives, come about when agreement does not apply. Infinitives arise regularly when the subject of an embedded sentence is removed by a transformation, or else placed into an oblique case, so that in either case agreement between subject and verb cannot take place. There are several ways in which the subject of an embedded sentence can be removed by a transformation. It can be deleted under identity with a noun phrase in the containing sentence, as in sentences like I decided to go and I forced John to go (cf. Rosenbaum 1967).

After prepositions, infinitives are automatically converted to gerunds, e.g. I decided to go vs. I decided on going; or I forced John to do it vs. I forced John into doing it. These infinitival gerunds should not be confused with the factive gerunds, with which they have in common nothing but their surface form.

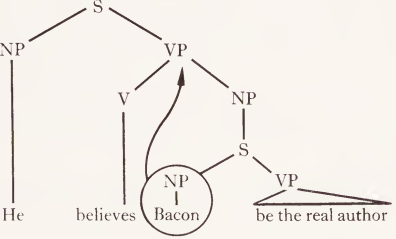

A second way in which the subject of an embedded sentence can be removed by a transformation to yield infinitives is through raising of the subject of the embedded sentence into the containing sentence. The remaining verb phrase of the embedded sentence is then automatically left in infinitive form. This subject-raising transformation applies only to non-factive complements, and yields the accusative and infinitive, and nominative and infinitive constructions:

He believes Bacon to be the real author

This seems to be Hoyle’s best book.

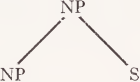

The operation of the subject-raising rule in object clauses can be diagrammed as follows:

The circled noun phrase is raised into the upper sentence and becomes the surface object of its verb.1

We reject, then, as unsuccessful the traditional efforts to derive the uses of the infinitive from its being ‘ partly a noun, partly a verb ’, or, perhaps, from some ‘ basic meaning’ supposedly shared by all occurrences of infinitives. We reject, also, the assumption of recent transformational work (cf. Rosenbaum 1967) that all infinitives are ‘for-to’ constructions, and that they arise from a ‘complementizer placement’ rule which inserts for and to before clauses on the basis of an arbitrary marking on their verbs. Instead, we claim that what infinitives share is only the single, relatively low-level syntactic property of having no surface subject.

Assuming that the subject-raising rule is the source of one particular type of infinitive complements, we return to the fact, mentioned earlier, that factive complements never yield these infinitive complements. We now press for an explanation. Why can one not say

*He regrets Bacon to be the real author

*This makes sense to be Hovle’s best book

although the corresponding that-clauses are perfectly acceptable? It is highly unlikely that this could be explained directly by the semantic fact that these sentences are constructed with factive predicates. However, the deep structure which we have posited for factive complements makes a syntactic explanation possible.

Ross (1967) has found that transformations are subject to a general constraint, termed by him the Complex Noun Phrase Constraint, which blocks them from taking constituents out of a sentence S in the configuration

For example, elements in relative clauses are immune to questioning: Mary in The hoy who saw Mary came back cannot be questioned to give * Who did the hoy who saw come back ? The complex noun phrase constraint blocks this type of questioning because relative clauses stand in the illustrated configuration with their head noun.

This complex noun phrase constraint could explain why the subject-raising rule does not apply to factive clauses. This misapplication of the rule is excluded if, as we have assumed, factive clauses are associated with the head noun fact. If the optional transformation which drops this head noun applies later than the subject-raising transformation (and nothing seems to contradict that assumption), then the subjects of factive clauses cannot be raised. No special modification of the subject-raising rule is necessary to account for the limitation of infinitive complements to non-factive predicates.

Another movement transformation which is blocked in factive structures in the same way is NEG-raising (Klima 1964), a rule which optionally moves the element NEG(ATIVE) from an embedded sentence into the containing sentence, converting for example the sentences

It’s likely that he won’t lift a finger until it’s too late

I believe that he can’t help doing things like that

into the synonymous sentences

It’s not likely that he will lift a finger until it’s too late

I don’t believe that he can help doing things like that.

Since lift a finger, punctual until, and can help occur only in negative sentences, sentences like these prove that a rule of NEG-raising is necessary.

Fact

This rule of NEG-raising never applies in the factive cases. We do not get, for example,

*It doesn’t bother me that he will lift a finger until it’s too late

from

It bothers me that he won’t lift a finger until it’s too late

or

*1 don’t regret that he can help doing things like that

from

I regret that he can’t help doing things like that.

Given the factive deep structure which we have proposed, the absence of such sentences is explained by the complex noun phrase constraint, which exempts structures having the formal properties of these factive deep structures from undergoing movement transformations.2

Factivity also erects a barrier against insertions. It has often been noticed that subordinate clauses in German are not in the subjunctive mood if the truth of the clause is presupposed by the speaker, and that sequence of tenses in English and French also depends partly on this condition. The facts are rather complicated, and to formulate them one must distinguish several functions of the present tense and bring in other conditions which interact with sequence of tenses and subjunctive insertion. But it is sufficient for our purposes to look at minimal pairs which show that one of the elements involved in this phenomenon is factivity. Let us assume that Bill takes it for granted that the earth is round. Then Bill might say:

John claimed that the earth was (*is) flat

with obligatory sequence of tenses, but

John grasped that the earth is (was) round

with optional sequence of tenses. The rule which changes a certain type of present tense into a past tense in an embedded sentence if the containing sentence is past, is obligatory in non-factives but optional in factives. The German subjunctive rule is one notch weaker: it is optional in non-factives and inapplicable in factives:

Er behauptet, dass die Erde flach sei (ist)

Er versteht, dass die Erde rund ist (*sei).

The reason why these changes are in part optional is not clear. The exact way in which they are limited by factivity cannot be determined without a far more detailed investigation of the facts than we have been able to undertake. Nevertheless, it is fairly likely that factivity will play a role in an eventual explanation of these phenomena.3

1 This subject-raising rule has figured in recent work under at least three names: pronoun replacement (Rosenbaum 1967); expletive replacement (Langendoen 1966); and it-replacement (Ross 1967). Unfortunately we have had to invent still another, for none of the current names fit the rule as we have reformulated it.

2 We thought earlier that the oddity of questioning and relativization in some factive clauses was also due to the complex noun phrase constraint:

*How old is it strange that John is?

*I climbed the mountain which it is interesting that Goethe tried to climb.

Leroy Baker (1967) has shown that this idea was wrong, and that the oddity here is not due to the complex noun phrase constraint. Baker has been able to find a semantic formulation of the restriction on questioning which is fairly general and accurate. It appears now that questioning and relativization are rules which follow fact-deletion.

3 This may be related to the fact that (factive) present gerunds can refer to a past state, but (non-factive) present infinitives can not. Thus,

They resented his being away is ambiguous as to the time reference of the gerund, and on one prong of the ambiguity is synonymous with

They resented his having been away.

But in

They supposed him to be away

the infinitive can only be understood as contemporaneous with the main verb, and the sentence can never be interpreted as synonymous with

They supposed him to have been away.

|

|

|

|

التوتر والسرطان.. علماء يحذرون من "صلة خطيرة"

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

مرآة السيارة: مدى دقة عكسها للصورة الصحيحة

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

نحو شراكة وطنية متكاملة.. الأمين العام للعتبة الحسينية يبحث مع وكيل وزارة الخارجية آفاق التعاون المؤسسي

|

|

|