Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension| Potts 2005: Some theoretical machinery and damn expressive adjectives |

|

|

|

Read More

Date: 2024-01-19

Date: 7-3-2022

Date: 7-1-2022

|

Potts 2005: Some theoretical machinery and damn expressive adjectives

To serve as a foundation for an account, I will adopt the general framework of Potts (2005) for representing expressive meaning. In this framework, expressive meaning (conventional implicatures) and ordinary truth-conditional (“descriptive”) meaning are computed compositionally, in parallel, and along distinct dimensions of semantic representation.

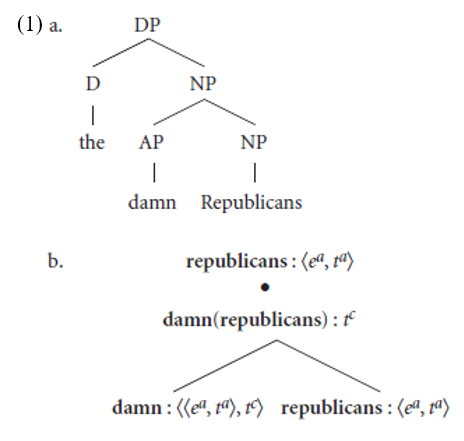

Potts proposes an analysis of nonrestrictive adjectives that focuses on adjectives that lexicalize a nonrestrictive meaning, e.g., damn.1 In these representations, a syntactic tree such as the one in (1a) is understood to correspond to a semantic one, as in (1b), that represents its interpretation.

Importantly, the node in (1b) corresponding to damn Republicans has two tiers, divided by a bullet. The higher of these represents ordinary descriptive meaning. The lower represents expressive meaning. For each formula in (1b), its type is explicitly indicated to the right of the colon.

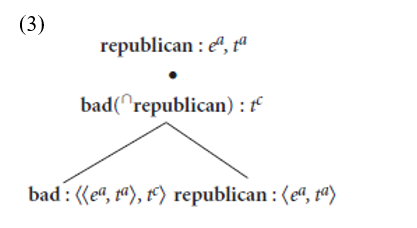

It is this type system that is the essence of how expressive meaning is represented. The core innovation is that (non-functional) types come in two flavors: one associated with an ordinary descriptive meaning (indicated with superscript a) and another with an expressive meaning (indicated with superscript c). A rule of semantic composition – CI Application2 – puts descriptive and expressive denotations together in the way (1b) reflects. This rule is roughly the expressive counterpart of the standard functional application rule. In (1b), then, the fact that damn contributes expressive meaning is reflected in its type. It is a function from ordinary properties (ea , ta ) to expressive truth values (tc), and thus applies to the denotation of Republicans to yield an expressive truth value. Because of how the CI Application rule works, the ordinary meaning of Republicans is simply passed on to damn Republicans, reflecting the fact that, apart from expressive meaning, these expressions are synonymous.

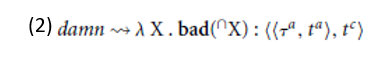

This of course reflects only how semantic composition proceeds. Substantively, Potts suggests that damn denotes a function that predicates of the kind correlate of its argument, specifically, that it denotes some kind of generalized disapproval predicate whose exact nature is irrelevant to the combinatorics, as in (2) (where ∩ is the nominalization function of Chierchia 1984, which maps a predicate to a corresponding kind, and Ù is an arbitrary type):

Very roughly, this says that damn is true of a property iff things that have that property are bad. Thus (2) could be spelled out more fully as (3):

1 He calls these “expressive” adjectives, using the term in a more narrow sense than I will here. He suggests, though, that analogous nonrestrictive uses of e.g. lovely work roughly similarly.

2 “CI” is for “conventional implicature.”

|

|

|

|

التوتر والسرطان.. علماء يحذرون من "صلة خطيرة"

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

مرآة السيارة: مدى دقة عكسها للصورة الصحيحة

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

نحو شراكة وطنية متكاملة.. الأمين العام للعتبة الحسينية يبحث مع وكيل وزارة الخارجية آفاق التعاون المؤسسي

|

|

|