Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension|

Read More

Date: 2024-03-29

Date: 2024-04-10

Date: 2024-05-14

|

Singapore’s language policy today treats Malay, Mandarin, Tamil and English as the four official languages. Malay is also the national language, having a primarily ceremonial function: the National Anthem is sung in Malay, and military commands are given in Malay. Malay’s national language status is primarily due to Singapore’s past when it was briefly a member of the Malaysian Federation until it achieved full independence in 1965. A reason for retaining Malay as the national language is essentially diplomatic: Singapore is surrounded by Malay-Muslim countries such as Malaysia, Indonesia and Brunei. Keeping Malay as the national language is intended to reassure these countries that Singapore will not go the way of becoming a Chinese state.

The other point to note is that, aside from English, there is a very specific reason why Mandarin, Malay, and Tamil are the three official languages. This is because the Singapore government groups the population into four main categories: Chinese, Malay, Indian, and ‘Others’. Here we see a modern-day version of the ‘capitan’ system, a policy of multiracialism, where equal status is accorded to the cultures and ethnic identities of the various races that comprise the population, and which, crucially, serves to maintain the compartmentalization and distinctiveness amongst the races.

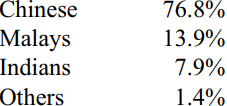

Singapore has a population of about 3.2 million, and its racial composition is as follows (2000 Census of Population):

‘Others’ is a miscellaneous category comprising mainly Eurasians and Europeans. The first three are specific ethnic communities, and these three official languages are their official mother tongues: Mandarin for the Chinese, Malay for the Malays, and Tamil for the Indians. There is no official mother tongue for ‘Others’ since this does not constitute a specific ethnic community. Thus, English is the only one of the four official languages that does not have a specific ethnic affiliation. This point is important to bear in mind because English is intended by the government to be a ‘neutral’ language, serving as the lingua franca for international and interethnic communication. It allows access to Western science and technology, and is the medium of education so that success in the school system depends to a great extent on proficiency in the language. As Gupta (1998: 120) points out, citing data from the 1990 census, this means that “(w)hatever measure of social class is taken, it is still the case that the higher the social class, the more likely it is that English is an important domestic language.”

The government clearly acknowledges the gatekeeping role that English plays in Singapore, but is also committed to the view that Singapore society is meritocratic. This notion of meritocracy is intimately tied up with the government’s commitment to multiracialism, which calls for the equal treatment for all ethnic groups. Where English is concerned, this means that the government does not want it to be seen as being tied to any particular ethnic community. That is, the role of English in the unequal allocation of social and economic capital is acceptable precisely because English is officially no one’s mother tongue. Thus, to accept English as a mother tongue for any ethnic community would undermine its officially neutral status.

Having encouraged the learning of English as a means of facilitating economic prosperity, the government is also concerned that English could act as the vehicle for unacceptable Western values. Here, the mother tongues are important because they are supposed to act as ‘cultural anchors’ that prevent Singaporeans from losing their Asian identities. This dichotomy between English and the mother tongues was underscored by Lee Kuan Yew (former Prime Minister and currently Senior Minister) in his 1984 Speak Mandarin Campaign speech, when he stressed that English is not “emotionally acceptable” as a mother tongue for the Chinese (the same rationale applies to the other communities):

One abiding reason why we have to persist in bilingualism is that English will not be emotionally acceptable as our mother tongue. To have no emotionally acceptable language as our mother tongue is to be emotionally crippled… Mandarin is emotionally acceptable as our mother tongue…It reminds us that we are part of an ancient civilization with an unbroken history of over 5,000 years. This is a deep and strong psychic force, one that gives confidence to a people to face up to and overcome great changes and challenges.

This bilingual policy of learning English and the mother tongue, known as “English-knowing bilingualism”, is a fundamental aspect of Singapore’s education system. Passage from one level to the next, including entry into the local universities, depends not only on academic excellence, but also on relative proficiency in one’s mother tongue. In 1986, Dr Tony Tan, then Minister for Education, underlined the importance of the bilingual policy:

Our policy of bilingualism that each child should learn English and his mother tongue, I regard as a fundamental feature of our education system… Children must learn English so that they will have a window to the knowledge, technology and expertise of the modern world. They must know their mother tongues to enable them to know what makes us what we are.

Together, this statement and the one by Lee Kuan Yew clearly lay out the government’s position on the relationship between English and the mother tongues. There is a division of labor where English functions as the language of modernity allowing access to Western scientific and technological knowledge while the mother tongues are cultural anchors that ground individuals to traditional values. By contrasting English with a mother tongue, the policy makes clear that English is not acceptable as a mother tongue.

|

|

|

|

"عادة ليلية" قد تكون المفتاح للوقاية من الخرف

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

ممتص الصدمات: طريقة عمله وأهميته وأبرز علامات تلفه

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

ندوات وأنشطة قرآنية مختلفة يقيمها المجمَع العلمي في محافظتي النجف وكربلاء

|

|

|