Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension|

Read More

Date: 2023-08-08

Date: 2023-04-07

Date: 12-2-2022

|

Semantic relativity

Studying semantics would be more straightforward if concepts could be taken as ‘given’ and simply assigned different labels by different languages, e.g. dog (English), Hund (German), Ci (Welsh) and so on. Such equivalence is, however, the exception rather than the rule, as anyone who has ever attempted a translation, even of a very basic kind, will know: languages divide up the world conceptually in different ways. French, for example, has no word for ‘shallow’ – the nearest equivalent is something like ‘not very deep’ (peu profond); on the other hand, French has two terms covering the semantic range of English cupboard, requiring the speaker to specify whether the item is wall-mounted (placard) or free-standing (armoire). The Japanese verb suu covers both ‘to smoke’ and ‘to sip’ in English.

Words which look very similar can have very different connotations: on the political spectrum liberal in British English is usually complimentary, implying tolerance and openness, but in the United States the same word is often used pejoratively, implying an over-readiness to accept fashionable left-of centre ideas and extend the scope of the state at the expense of personal freedom, while in French libéral has exactly the opposite connotations, implying an over-readiness to dismantle the state and extend the free market.

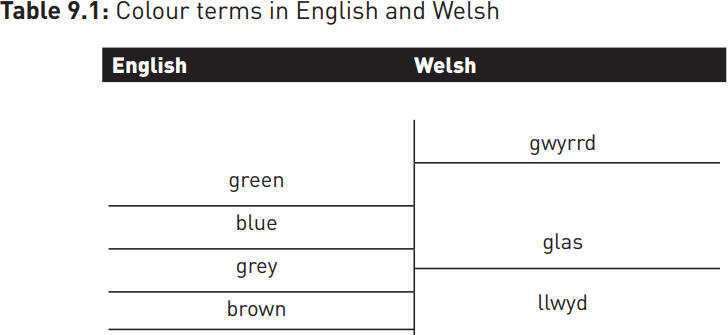

Color terminology offers a good example of lexical non-equivalence between languages, as can be seen in the examples of English and traditional Welsh below:

The semantic range of Welsh glas overlaps partly with that of English green, blue and grey, while llwyd overlaps partly with grey and brown. Russian, by contrast, has two words covering English blue: goluboi corresponds broadly with sky blue or light blue while sinii is dark blue. Many languages, including Vietnamese, Kurdish and Kazakh, do not distinguish blue and green as English does.

The semantics of color has been a focus of scholarly attention since the publication in 1969 of Berlin and Kay’s Basic Color Terms: Their Universality and Evolution. Setting aside complex color expressions (pea-green, sky-blue-pink and so on) and focusing only on basic terms, Berlin and Kay examined a sample of 98 languages spoken across the world and argued for a universal hierarchy, acquired by languages in chronological sequence. A very small number of languages, for example Dugum Dani, spoken in western New Guinea, are still at the first stage, in which only two colors are distinguished: prototypically ‘white’ and ‘black’, but covering the semantic area of ‘light-’ and ‘dark-’colored respectively. The next stage is the acquisition of ‘red’ as a third color term, followed by ‘green’ and/or ‘yellow’, and then ‘blue’. Russian and Italian have most basic color terms, with 12; English has 11.

Berlin and Kay’s hierarchy has been modified and refined since the publication of Basic Color Terms, but some critics have challenged their universalist claims, viewing color as a culture-specific concept. These critics argue that a bias towards western assumptions and perceptions underpinned much of their methodology.

|

|

|

|

علامات بسيطة في جسدك قد تنذر بمرض "قاتل"

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

أول صور ثلاثية الأبعاد للغدة الزعترية البشرية

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

مكتبة أمّ البنين النسويّة تصدر العدد 212 من مجلّة رياض الزهراء (عليها السلام)

|

|

|