Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension|

Read More

Date: 19-4-2022

Date: 17-5-2022

Date: 23-5-2022

|

The importance of old or prior knowledge (assumptions) in understanding cannot be overestimated. We use such knowledge to enrich our understanding of what people say, make what they say cohere and even make predictions about what they are going to say. Unfortunately, in pragmatics the way in which we use such knowledge has generally been underestimated, something which stands in contrast with work in the cognitive sciences. Pragmatics has been focused on the kind of pseudo-logical inferencing to be discussed at length (notably, Grice’s Cooperative Principle, 1975), which is characterized by mechanisms for drawing conclusions from premises. But a large part of meaning is understood through known associations, that is associative inferencing or knowledge-based inferencing. For example, if you know that that kind of utterance X, said by that kind of speaker Z, in that kind of context Y, usually has that kind of meaning W, you may simply arrive at the meaning on the basis of what usually happens. Thus the utterance how are you? said in a doctor’s surgery to a patient is usually taken as a question eliciting information about symptoms and so on; whereas the same utterance said in an everyday context to an acquaintance is usually taken as phatic talk requiring a suitably phatic response (often in British English a repetition of how are you?). These scenarios do not require one to take the utterance and context as premises and then deploy a mechanism for calculating an implied bit of meaning. The important role of associative inferencing has been recognized by Recanati (2004) and championed by Mazzone (2011). It is important because it accounts for much of the inferencing we do. People are “cognitive misers” (Taylor 1981) and associative inferencing represents a less cognitively effortful way forward.

To understand how knowledge works, we need a theory of knowledge. The leading theory is schema theory, though that precise label may not be the one used (“frames”, “scripts” and “scenarios”, have been used in the literature, each within a somewhat different tradition and with a somewhat different emphasis).1 Schema theory has been formulated by cognitive psychologists and researchers from other fields (e.g. Bartlett [1932] 1995; Neisser 1976; Schank and Abelson 1977). It has been used to account for how people comprehend, learn from and remember meanings in texts. Essentially, the idea is that knowledge is retrieved from long-term memory and integrated with information derived from the utterance or text, or indeed context, to produce an interpretation. The term “schema/schemata” refers to the “well integrated chunks of knowledge about the world, events, people, and actions” (Eysenck and Keane 2000: 352). They are usually taken to be relatively complex, higher-order, clusters of concepts, with a particular network of relationships holding those concepts together, and are assumed to constitute the structure of long-term memory. What have schemata got to do with inferencing? Schemata enable us to construct an interpretation that contains more information than we receive from the language itself. We can supply or infer extra bits of information – default values – from our schematic knowledge.

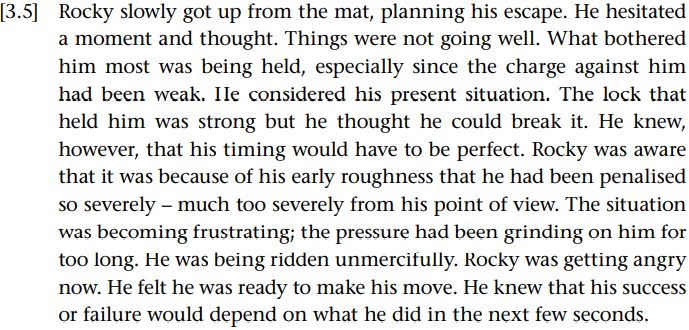

Andersen et al. (1977) conducted an experiment that conveniently illustrates how this inferencing might work. They asked people to read the following fictional passage:

The key problem here is trying to work out the discourse topic. To begin with, who is Rocky? The text tells us about, for example, his spatial circumstances (he is on a mat and held by the lock), his goal (planning his escape), his evaluation of the situation (things were not going well), his history (his early roughness, the pressure had been grinding on him for too long), his evaluation of his plan to achieve his goal. (He felt he was ready to make his move. He knew that his success or failure would depend on what he did in the next few seconds.) We also, of course, learn that Rocky is his name, connoting that he is male (and quite possibly North American rather than British). But the text does not actually tell us who Rocky is or even where he is. Note that many of the clues are in referring expressions, especially definite noun phrases (Rocky, the mat, his escape, the charge, his present situation, the lock and so on). We discussed this very

phenomenon, where we argued that referring expressions do not passively rely on a specific shared context for interpretation (i.e. common ground), but produce or trigger a specific shared context in which they can be interpreted – they trigger a schema by virtue of the fact that they are stereotypical components of that schema

People understanding language generally try to activate a schema that will provide a scaffold for interpreting the incoming linguistic information. The alternative – keeping all the separate bits of information in the cognitive air – would be mentally taxing, to say the least, and would not constitute an understanding of the passage. Once activated, a schema gives rise to expectations (i.e. default values) – these expectations are knowledge-based associative inferences. Andersen et al. (1977) discovered that most of their informants thought that the discourse topic of the passage concerned a convict planning his escape from prison. Accordingly, referring expressions such as Rocky, the pronouns (e.g. he, his) and the definite noun phrases (e.g. the situation) could be assigned suitably coherent referents (e.g. convict, prison cell). Further, informants could disambiguate words such as charge or lock to fit the default values of that schema: the charge is a legal charge; the lock is the lock on the door. A door has not in fact been mentioned, let alone a prison cell, but these can be readily inferred, thereby enriching the interpretation. However, one group of people had an entirely different interpretation of the discourse topic. Men who had been involved in wrestling assumed that it was about a wrestler caught in the hold of an opponent. Thus, for example, charge is a physical charge by the opponent; the lock is a hold (possibly headlock) the opponent has on him.

Most informants gave the passage one distinct interpretation and reported being unaware of other perspectives while reading. The particular schema (or schemata) deployed in interpretation depends upon the experiences, including cultural experiences, of the interpreter. A person’s experiences constitute the basis of their schemata. Fredric Bartlett’s (1932[1995]) early pioneering work in schema theory was partly designed to explore cultural differences in interpretation (see also the experiment by Steffenson et al. 1979). Schema theory has been used more recently in the context of crosscultural pragmatics (e.g. Scollon & Scollon 1995). For example, we have schemata or, to use Schank and Abelson’s (1977) term, scripts about typical sequences of actions in particular contexts. But these vary culturally. For example, in a coffee bar in the UK it is usual to get your food (or order your food and then get it) before paying and then receiving a receipt. In contrast, in Italy it is usual to say what you want, pay for it, get a receipt and then get your food (sometimes having ordered it from a different person). A recipe for cross-cultural trouble!

|

|

|

|

علامات بسيطة في جسدك قد تنذر بمرض "قاتل"

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

أول صور ثلاثية الأبعاد للغدة الزعترية البشرية

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

مكتبة أمّ البنين النسويّة تصدر العدد 212 من مجلّة رياض الزهراء (عليها السلام)

|

|

|