Phonological alternations

We concluded that the (a) subset of roots are underlyingly /kaj, aw, pi, ko, age, mu/ because those are the parts of words that invariantly correlate with the choice of a particular root. A further consequence of that conclusion is that the roots in (b) and (c), which behave differently, should have a significantly different-looking underlying form. The roots in (30b) have the surface realizations [ka:ʔ, ma:ʔ, awʔ, koʔ, abeʔ] and [ka:, ma:, aw, ko, abe]. The roots of (30a) underlyingly end in a glide or vowel, and since the roots in (30b) behave differently, those roots must not end in a vowel or glide, which leads to the conclusion that the roots of (30b) are /ka:ʔ, ma:ʔ, awʔ, koʔ, abeʔ/, i.e. these roots end in a glottal stop.

Similar reasoning applied to the roots of (30c) leads to the conclusion that these roots are /tun, awn, in, na:n, arawn, kajn/. Again, the roots have two types of surface realization, and the alternative theory for (30c) that the roots are /tu, aw, i, na:, araw, kaj/ can be ruled out on the grounds that this would incorrectly render the (a) and (c) roots indistinguishable. The distinguishing feature of the (c) roots is that they all end with a nasal.

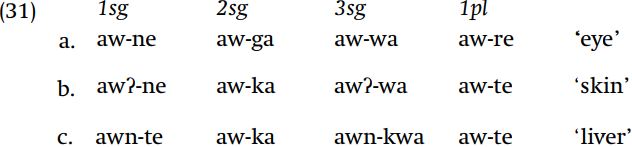

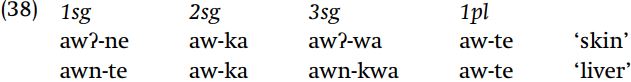

Having sorted out the underlying forms of the roots, we can turn to the suffixes, drawing one representative from each phonological class of roots.

One fact stands out from this organization of data, that while both the 1sg and 1pl suffixes have the variant [te] somewhere, these suffixes cannot be the same because they act quite differently. A second fact which can be seen from these examples is that the 1pl and 2sg suffixes are similar in the nature and context of their variation. Both alternate between a voiceless stop and a voiced consonant – we can suspect that [r] is the surface voiced counterpart of [t]. And the voiced alternant appears after roots which underlyingly end in a glide or a vowel, whereas the voiceless variant appears after an underlying nasal or a glottal stop.

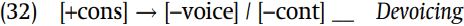

Nasals and glottal stops have in common the fact of being [-continuant], and glides and vowels have in common the fact of being [+voice, -cons]. This gives rise to two theories regarding the underlying forms of the 2sg and 1pl and the rules that apply to those suffixes. First, we could assume /ga, re/ and the following rule to derive the voiceless variant.

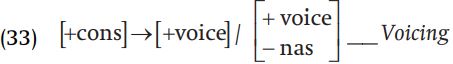

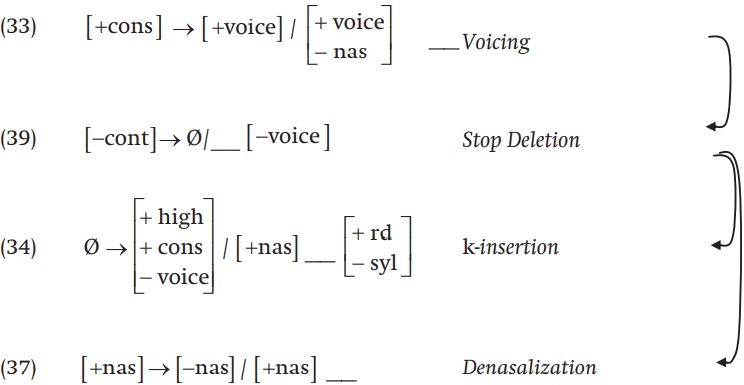

Alternatively, we could assume /ka, te/ and the following voicing rule.

Either analysis is, at this point, entirely reasonable, so we must leave the choice between these analyses unresolved for the moment. We might reject (33) on the grounds that it requires specification of an additional feature, but such a rejection would be valid only in the context of two competing complete analyses which are empirically correct and otherwise the same in simplicity.

The 3sg suffix surfaces as [kwa] and [wa], the former after a nasal and the latter after an oral segment. That leads to two pairs of rule and underlying representation. If the underlying form of the suffix is /wa/ then there is a rule inserting [k] between a nasal and w.

If the suffix is underlyingly /kwa/, a rule deletes k after an oral segment before w.

Finally, the 1sg suffix might be /ne/ or it might be /te/. As noted above, we could rule out the possibility /te/ if we knew that the 1pl suffix is /te/. This means that a choice of /te/ for the 1s entails that the 1pl suffix is not /te/, therefore is /re/. If the 1sg suffix is /ne/, on the other hand, the 1pl could be either /te/ or /re/. If the 1sg suffix is /te/, then the following rule is required to derive the variant [ne].

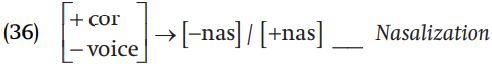

If the suffix is /ne/ then the following rule derives the variant [te].

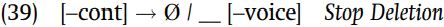

Besides three rules which affect the initial consonant of the personal suffixes, a rule deletes root-final glottal stop and nasals. In comparing roots with deleted consonants, we see that both glottal stop and nasals delete in the same context: before the 2sg and 1pl suffixes (which we have determined are /ka, te/ or /ga, re/).

What phonological property unifies these two suffixes and distinguishes them from /ne ~ te/ and /kwa ~ wa/? A simple answer would be that these suffixes begin with voiceless stops – if we assume that the suffixes are /ne/ ‘1sg,’ /ka/ ‘2sg,’ /wa/ ‘3sg,’ and /te/ ‘1pl.’ We will pursue the consequences of that concrete decision about suffixes.

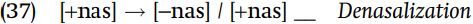

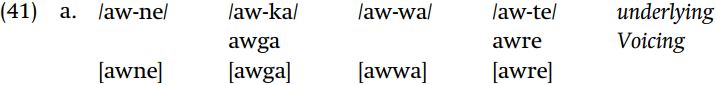

The choice of underlying forms for suffixes entails certain choices for rules: in this analysis, we are committed to Voicing (33), k-insertion (34), and Denasalization (37). The rule deleting root-final stops is as follows.

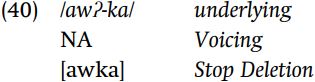

We must determine how these four rules are ordered. Although Voicing affects underlying voiceless stops after voiced oral segments, we see from [awka] ‘your skin’ from /awʔka/ and [awka] ‘your liver’ from /awn-ka/ that Voicing precedes Stop Deletion.

The structural description of the latter rule is not satisfied in /awnka, awʔka/, hence Voicing does not apply. Subsequently, Stop Deletion applies to eliminate n and ʔ before a voiceless stop.

Stop Deletion obscures the Voicing rule, because it creates surface counterexamples to the prediction of Voicing that [k, t] should not follow a vowel or glide.

The ordering of k-insertion is also a matter of concern, since that rule inserts a voiceless stop but Stop Deletion is not triggered by inserted k. Underlying /awn-wa/ undergoes k-insertion to become [awnkwa], a form which satisfies the structural description of Stop Deletion (which would delete the nasal), yet the nasal is not deleted. This indicates that k insertion follows Stop Deletion – k created by the former rule is not present when Stop Deletion applies.

We can also determine that Denasalization follows Stop Deletion, since the former rule creates a sequence of nasal plus stop – /awn-ne/ ! [awn-te] ‘my liver’ – and Stop Deletion applies to a sequence of nasal plus stop – /awn-te/ ! [awte] ‘our liver’ – yet Stop Deletion does not apply to the output of Denasalization. In summary, the rules of Fore which we have proposed, with their ordering, are as follows.

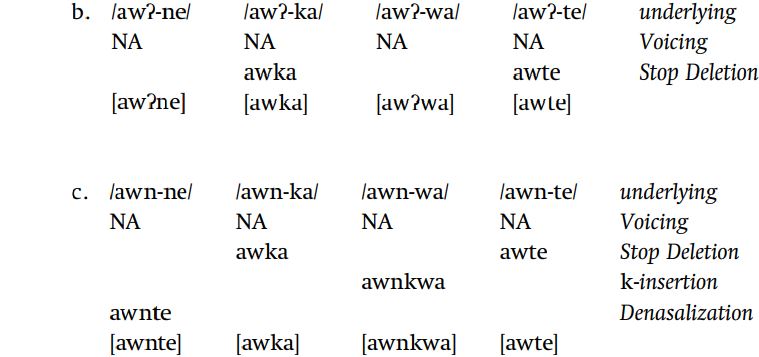

To be sure that our analysis works, derivations of relevant examples are given in (40).

الاكثر قراءة في Phonology

الاكثر قراءة في Phonology

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة