Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Optimality Theory (OT)

المؤلف:

Mehmet Yavas̡

المصدر:

Applied English Phonology

الجزء والصفحة:

P214-C8

2025-03-20

1856

Optimality Theory (OT)

Explanations regarding the interaction of the differential effects of the inter-language components over time, and the changing nature of the learner’s language, have also been analyzed by a recent theoretical approach called Optimality Theory (OT). In the following, we will briefly describe the principles of OT and then give a few examples of its application to L2 phonology.

OT views language as a system of conflicting universal constraints, and different phonological systems as a result of different rankings of these constraints. In other words, languages have different phonologies, because

(a) languages differ in the importance they attach to various constraints (constraint hierarchy), and

(b) constraints may be contradictory, and thus be violated; if two constraints are contradictory, the one that is ranked higher will have priority.

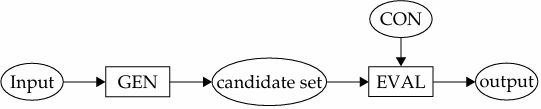

OT has two levels known as the ‘input’ (underlying form), and ‘output’ (surface phonetic form). The theory assumes that the possible output forms for a given input are produced by a mechanism called GEN (the ‘Generator’) and then evaluated by a mechanism called EVAL. An evaluation for the optimal phonetic output is made by screening the candidates through the constraints, and the candidate that violates the fewest constraints is chosen as the correct output. This can be shown in the following diagram (Archangeli 1999):

Constraints are of two conflicting types:

(a) markedness constraints, which capture the generalizations on linguistic structures that commonly or uncommonly occur in languages (‘unmarked’ vs. ‘marked’). Unmarked structures are universal and innate and do not have to be learned, while marked features are specific to languages and have to be learned. Sample markedness constraints include “NO CODA. Syllables must not have codas”; “*COMPLEX. No clusters”; “*V NASAL. Vowels must not be nasals”.

(b) faithfulness constraints, which require that input and output match, so that properties of the input correspond in identity to those of the output. These are of three kinds:

MAX-IO: requires that input segments must correspond to output segments (i.e., the input is maximally represented in the output); thus there should be no deletion.

DEP-IO: requires that output segments must match input segments (i.e. the output must be entirely dependent on the input); thus, there should be no insertion.

IDENT-IO(F): requires that the input representations of place, manner, and voice features should appear in the output; thus, there should be no feature change or substitution.

In all grammars, the constraints are conflicting (Kager 1999), and thus it is not possible to satisfy all constraints simultaneously. The conflict between constraints is resolved by ranking the constraints in a language-specific fashion (constraint hierarchy). For example, one of the markedness constraints, *COMPLEX ONSET, which dictates “no onset clusters”, is ranked higher in Turkish, which has no onset clusters, than in English, which allows onset clusters. The optimal output (phonetic form) will be the one that incurs the least serious violations of a set of ranked constraints. Consequently, any output candidate that violates higher ranked constraints will not be the one that will survive.

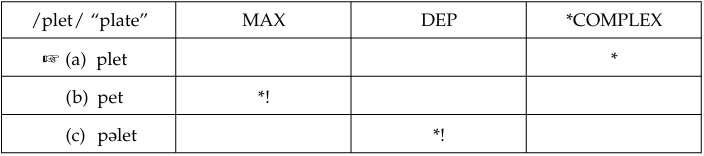

The expression of ‘domination’ (or ‘precedence’) among the constraints is given in OT by a left-to-right ordering, with the highest ranked constraint being on the left. In prose, the ranking is expressed with the use of double arrowheads: A >> B (constraint A outranks constraint B). We will illustrate these in the following sample tableau, a two-dimensional table in which the constraints are listed across the top line and the candidates down the side.

The input that is evaluated is placed at the top left corner. A * in a cell indicates that the form of that row violates the constraint in that column, while *! indicates that such a violation is fatal and thus eliminates that form from further consideration. The optimal (winning) form is marked with a little hand, ☞. In this tableau, the optimal output is the faithful [plet], because the only constraint it violates is the low-ranked markedness constraint *COMPLEX. The second candidate, [pet], violates MAX, which prohibits deletion, and the third candidate, [pəlet], violates DEP, which prohibits insertion. Both of these constraints are higher ranked than *COMPLEX, but the relative ranking of MAX and DEP does not seem crucial.

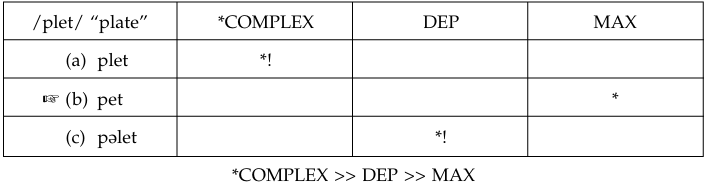

If, on the other hand, the output is [pet], as commonly attested in child speech via a cluster reduction process, then we will have the following:

Here, *COMPLEX is the highest-ranking constraint and thus is placed in the leftmost position. Candidate (a) violates the highest ranking and is thus eliminated from further consideration. Between the two remaining faithfulness constraints, DEP (no insertion) and MAX (no deletion), the ranking will be in that order. Candidate (c), [pəlet], violates DEP by inserting a vowel, and won’t be selected. Candidate (b) violates the lowest-ranked MAX by deleting a con sonant from the input, and thus is the choice.

L2 phonology and OT

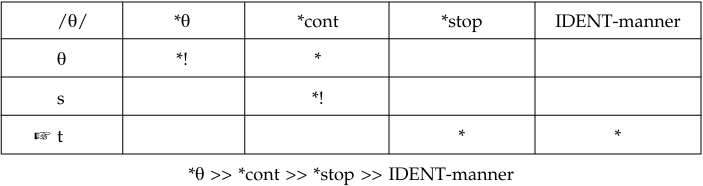

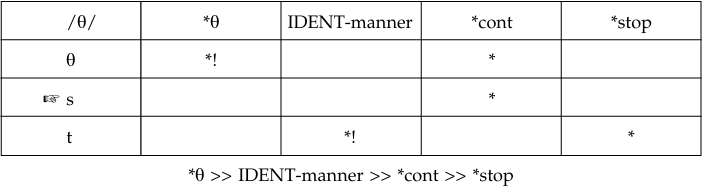

In the following, we will give examples from OT approaches to some of the observed phenomena in L2 phonology. Our first example comes from a segmental substitution of the English /θ/ as [s] or [t] in languages that lack the interdental fricative (Lombardi 2003). What is interesting here is that some languages use [s] and others utilize [t] despite the fact that all first languages have both segments. The idea advanced by Lombardi is that languages that use the substitute [s] (e.g. German, French, Japanese) do so because of native language transfer, whereas others that use the substitute [t] (e.g. Turkish, Persian, Russian) do so because of a universal markedness constraint (fricatives are more marked than stops, thus *[continuant] >> *[stop]). Also relevant is the markedness constraint *θ, which conspires against the occurrence of interdentals in inventories. Finally, the relevant faithfulness constraint for this substitution is IDENT-manner, which is defined by the manner features [stop], [continuant], and [strident]. The explanation lies in the ranking of the manner faithfulness constraint relative to the markedness constraints. We have the following tableaux for the two different substitutions. First, we look at the situation where /θ/ is replaced by [t]:

Here, the markedness constraints are higher than the IDENT-manner, and the candidate that violates the lower-ranked constraint is chosen.

Second, we look at /θ/ being replaced by [s]:

Because of the re-ranking of the faithfulness constraint (IDENT-manner), [s] violates a lower-ranking markedness constraint and is the substitute.

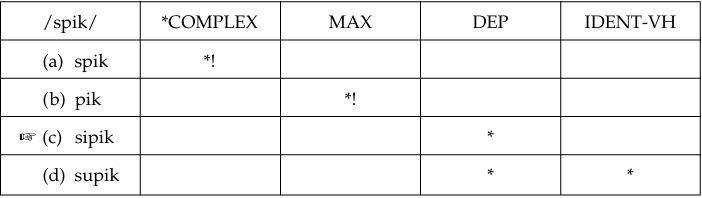

Our second example will be on the native language transfer effects on complex onsets. Turkish does not allow complex onsets. When Turkish speakers learn English, target complex onsets are rendered with an epenthetic vowel (e.g., group [grup] → [gurup], speak [spik] → [sipik]). The situation can be described in the following way:

The leftmost constraint, *COMPLEX, is a markedness constraint against having onset clusters. The second and third are faithfulness constraints that disallow consonant deletion and vowel insertion. The last one relates to the vowel harmony. Candidate (a) violates the highest ranking, *COMPLEX, and is eliminated from further consideration. The remaining three avoid violating *COMPLEX; however, they do this at the expense of other constraints. Candidate (b) violates MAX (no deletion) and candidates (c) and (d) violate DEP (no insertion). In Turkish, DEP is more violable than MAX, and thus is placed lower in the hierarchy. The epenthetic vowel in Turkish is chosen from the set of four high vowels, /i, y, ա, u/, following the vowel harmony rules that call for agreement with the other vowel, /i/, in backness (thus, /ա/ and /u/ are eliminated) and in rounding (thus, /y/ is eliminated). Consequently, /i/ is inserted and candidate (c) is the surviving one.

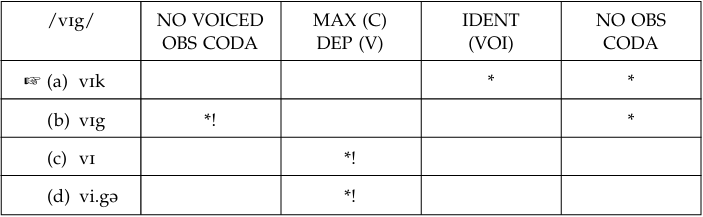

Our final example comes from final obstruent devoicing. As mentioned earlier, this is a common process seen in the speech of many learners of English coming from a variety of languages such as German, Russian, Turkish, Dutch, and Bulgarian, to name a few. In such cases, the explanation is based on native language interference, as these languages do not allow voiced obstruents in final position. Final devoicing, however, has also been observed in learners of English whose language does not allow any obstruents (voiced or voiceless) in final position. Broselow et al. (1998) analyze such a situation in Mandarin L1 speakers learning English. While English allows both voiced and voiceless stops in final position, Mandarin lacks both in this position. When Mandarin speakers learn English, the clash created by the above-mentioned mismatch is resolved by a variety of different strategies including epenthesis (e.g. bag → [bægə]), deletion (e.g. bag → [bæ]), and final devoicing (e.g. bag →[bæk]). The last option is an unexpected one because there is no such rule in the native language. Thus, the outcome is not a result of interference, nor is it coming from the target language.

Broselow et al. analyze the situation with the following two markedness constraints:

• NO VOICED OBS CODA: syllable codas may not contain voiced obstruents;

• NO OBS CODA: syllables may not contain obstruent codas;

and the three faithfulness constraints:

• MAX (no deletion of consonants);

• DEP (no vowel insertions); and

• IDENT (VOI): an output segment should be identical in voicing to the corresponding input segment.

Initially, the constraint ranking for Mandarin, which does not allow any obstruent codas, will be: NO OBS CODA, NO VOICED OBS CODA >> MAX, DEP, IDENT (VOI).

The learners who devoice the target final stops (instead of deleting the stop, or inserting a vowel after the stop) produce an unmarked form that is not compatible with either Mandarin or English. Broselow et al. suggest that these learners have re-ranked NO OBS CODA relative to NO VOICED OBS CODA by moving the latter lowest in the hierarchy. The situation is characterized in the following tableau:

By re-ranking the constraints in this way, Mandarin speakers who devoice target English voiced stops are in a situation comparable to German speakers who produce all English target final stops (voiced and voiceless) as voiceless.

الاكثر قراءة في Phonology

الاكثر قراءة في Phonology

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)