Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension|

Read More

Date: 2023-10-13

Date: 2023-04-05

Date: 2023-04-28

|

Some other parts

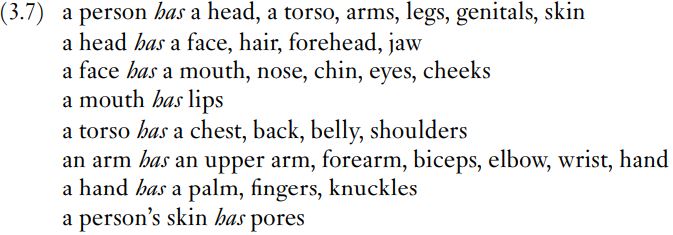

The body is a source of metaphors, for instance lose one’s head, meaning ‘panic’. The has-relation applies between various words denoting body parts. Person is an ambiguous word denoting either a physical person – who can, for instance, be big or ugly – or the psychological individual – who can be kind or silly and so on. The physical person prototypically has a head, has a torso, has arms, has legs, has genitals and has a skin. These parts and some of the parts that they, in turn, prototypically have are set out in (3.7).

It was pointed out that semantic description is different from the compilation of an encyclopedia. Semantics is not an attempt to catalogue all human knowledge. Instead, semanticists aim to describe the knowledge about meaning that language users have simply because they are users of the language. Anatomists, osteopaths, massage practitioners and similar experts have a far more detailed vocabulary for talking about body parts than just the terms in (3.7). It is safe to assume that any competent user of English knows the meanings of the words in (3.7), and the has-relations listed there are the basis for inferences. If you are told that the mountain at Machu Picchu looks like a face, you can expect it to have parts corresponding to a mouth, nose, chin, eyes and cheeks, but, in an ordinary conversation, it would be unreasonable to expect that there should be parts corresponding to everything shown in an anatomy book’s treatment of the face.

For the sake of clarity, I avoided using the word body in (3.7) because body is ambiguous and two of its several different senses could have been used in that example. One sense (and, to keep track of the difference, I’ll call it body1) is synonymous with (physical) person and another sense (body2 for convenience of reference) is synonymous with torso. The first line of (3.7) could have been written as ‘a body1 has a head, a body2, arms, legs, genitals, skin’. Readers who use the word body2 in preference to torso might have liked that better.

A prototype chair has a back, seat and legs. Interestingly the words back and legs are also body part labels. The body part labels head, neck, foot and mouth are used to label parts of a wide range of things: for example, a mountain has a head and foot; lampposts and bottles both have necks; caves and rivers have mouths. Presumably this indicates a human tendency to interpret and label the world by analogy with what we understand most intimately, such as our own bodies.

|

|

|

|

علامات بسيطة في جسدك قد تنذر بمرض "قاتل"

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

أول صور ثلاثية الأبعاد للغدة الزعترية البشرية

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

مكتبة أمّ البنين النسويّة تصدر العدد 212 من مجلّة رياض الزهراء (عليها السلام)

|

|

|