Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension|

Read More

Date: 2023-09-19

Date: 2023-09-22

Date: 2024-01-01

|

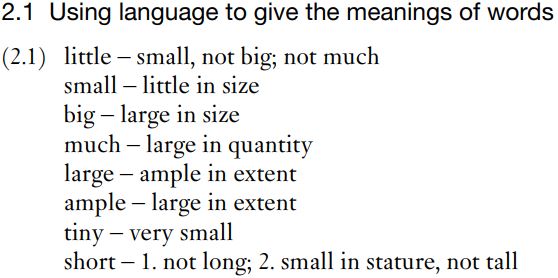

Adjective meanings

Overview

Cruse (2000: 289) notes that adjective meanings are often one dimensional. Think of pairs like thin–thick, fast–slow, cool–warm, young–old, true–false. Thickness concerns only a minor dimension, not length or width; for speed, one can ignore temperature, height, age; and so forth. This makes adjectives a good starting point for trying to understand word meaning. This topic concentrates on various kinds of meaning relationship between adjectives, mainly relationships of similarity and oppositeness. Three other topics are broached: meaning postulates, gradability, and how to account for the meanings that arise when adjectives modify nouns.

The fragments of entries shown in (2.1) could plausibly appear in a dictionary. In the entry for short, the numbers 1 and 2 distinguish two different senses of the word. It is unlikely you would look up words as familiar as these, but the items in (2.1) illustrate the circularity of a monolingual dictionary. It is reminiscent of a puppy chasing its own tail. Nonetheless, such a dictionary can give useful indications of word meanings. The cryptic hints in (2.1) catalogue relationships between word meanings, such as that all these words have something to do with size/quantity/extent; that little and small have closely similar meanings, as do large and big; that big is opposite in meaning to little; and so on. If the network can be anchored in a few places – if the meanings of some basic words are known – then it is a useful system.

In early childhood we come to know the denotations of our first words in the course of close encounters with the world, painstakingly mediated by our caregivers (sometimes with point-and-say demonstrations of the kind called ostension). But once we have a start in a language, we learn the meanings of most other words through language itself: by having them explained to us (as when a child is told that tiny means ‘very small’) or by inference from the constructions words are put into (for example, when an older child realizes from the title of Gerald Durrell’s book My Family and Other Animals that there is a view according to which people are classified as animals).

The focus of the present topic is the systematic description of meaning relationships within a language, between the senses of expressions (mainly words, but some phrases too). The aim is to state economically and insightfully which expressions are equivalent in meaning to which others – or contrast with them in various ways – according to the linguistic knowledge of individuals competent in the language.

What about denotation? Semanticists tend to regard the building up of links between words and the world, and the perceptual processes that allow us to recognize the “things” that are denoted by words, as a matter for psychologists. However, the semantic study of sense relations contributes to this because the sense of a word places limits on what it can denote. And formal semantics is relevant too because the compositional senses of larger expressions delimit what they can denote.

|

|

|

|

علامات بسيطة في جسدك قد تنذر بمرض "قاتل"

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

أول صور ثلاثية الأبعاد للغدة الزعترية البشرية

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

مكتبة أمّ البنين النسويّة تصدر العدد 212 من مجلّة رياض الزهراء (عليها السلام)

|

|

|