Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Past Simple

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Passive and Active

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Grammar Rules

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Semantics

Pragmatics

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

An alternative analysis

المؤلف:

APRIL McMAHON

المصدر:

LEXICAL PHONOLOGY AND THE HISTORY OF ENGLISH

الجزء والصفحة:

117-3

2024-12-06

184

Given the numerous problems encountered and engendered by these analyses, it is clear that there is no harm in attempting to find a more concrete solution. The first step in this direction is to consider again the status of the [j] glide in [jū]. In all the accounts discussed, this glide was taken to be inserted by rule; however, this is by no means a self-evident assumption, and the [jū] sequence might also be considered a diphthong, at least underlyingly.

It certainly seems that at least one historical source for [jū] was diphthongal. Strang (1970) and Stockwell (1990) agree that Middle English <ewe>, <fewe>, <newe>, <triwe>/<truwe>, from Old English <eowu>, <fēawe>, <nēawe>, <trēowe>/<trīewe> suggest a shift of the /w/ from the onset of the second syllable into the nucleus of the first, giving [iu] or [εu]. Stockwell proposes that this resyllabification of /w/ caused the first part of the earlier diphthong to move in turn into the syllable onset; Strang (1970: 158) sees this `syllabicity shift' as independent of the development of /w/, but accepts that <yeue>, ,<yowe>, <yoo> spellings, mainly from Northern dialects in the late thirteenth century, support a change from a falling to a rising diphthong. This diphthong subsequently merged with late Middle English /y:/ in French loans of the issue, virtue, leisure type, where Stockwell proposes a development of Cüu>Ciu>Ciiu>Ciu. In cases like blue, shrew, where Strang argues the /j/ was later lost, there is a further merger with /u:/ from Vowel Shift of earlier /o:/ in doom, moon, boot. More recent evidence suggests that the acceptability of /j/ in clusters has been progressively restricted. For instance, Gimson (1980) lists /lj-/ as acceptable in lewd [ljūd], lure [ljʊə], and lucid [ljūsɪd]. However, no [j] appears in loom, loop, loose, lunar and lute, and even in the forms Gimson lists, [lj] is now only common in conservative RP and with older speakers. However, /lj/ is permissible if /l/ can be resyllabified into the coda of the preceding syllable; thus, postlude and interlude have [ū] but prelude has [jū]. In most American English, [j] is also absent after coronals, unless the following vowel is unstressed, as in venue [vεnjū], virtue [vɪrtjū] or [vɪrtʃū] and issue [ɪsjū] o r[ɪʃū].

Two questions arise here: is there evidence for still regarding /jū/as a rising diphthong in Modern English, and how do we account for the contexts in which /j/ was lost? To begin with the diphthong question, there are indeed analyses of /jū/ where an underlying diphthong is posited. For instance, Anderson's (1987) Dependency Phonology analysis treats [ jū] as a diphthong [ɪu], derived either from long, tense /ɪu/, or from short, lax /ɪV/; the latter is an underlying combination of {i} plus the `unspecified vowel'. I will not pursue Anderson's analysis in detail, partly because it relies on under- and un-specification, theoretical devices not employed here; what is more interesting is the speech error evidence, from Shattuck-Hufnagel (1986), which he uses to support it. This evidence, however, is not unambiguous. Shattuck-Hufnagel argues that speech error patterns are important in deciding whether [j] is nuclear or not, since earlier work has shown that `polysegmental error units tend to respect the onset-rhyme boundary' (1986: 130) ± in clamp, for instance, [l] may form an error unit with the preceding [k], since both are in the onset, but not with the following vowel. On the basis of seventy [jū] errors from the MIT error corpus, Shattuck-Hufnagel observes that, although the [jū] sequence may on occasion function as an error unit, as in m[jū] sarpial for mars[jū]pial, in a far larger number of cases, thirty-three in all, [j] constitutes an error unit in isolation from [ū], interacting with another C (see (3.33)).

The fact that `a /j/ before /ū/ interacts freely with other onset consonants in errors' (Shattuck-Hufnagel 1986: 132) might suggest that /j/ itself forms part of the onset. There are, however, no examples in the corpus of C/j/ acting as an error unit, as would be expected if /j/ is indeed an onset consonant, given that entire onsets composed of CC clusters do tend to function as error units in other cases.

Davis and Hammond (1995) identify various asymmetries between CyV and CwV sequences in American English, arguing that `the onglide in a CwV sequence is treated as an onset while the onglide in a CyV sequence is treated as co-moraic with the following vowel' (1995: 160). Davis and Hammond (1995: 176) explicitly discount error evidence as inconclusive, but present evidence from two other sources. First, there are certain co-occurrence restrictions involving /j/: notably, it can appear after sonorant /m/ in mute, music (and likewise /n/ in British English), although this does not otherwise cluster as C1; in American English again, clusters of coronal plus [j] are prohibited, which Davis and Hammond attribute to a homorganicity condition holding between onset and nucleus; and the vowel following [j] must be [u:]. Davis and Hammondalso present data from two language games, Pig Latin and the Name Game, which seem to support a nuclear analysis of [j], although evidence is arguably stronger from the latter. In the Name Game, the initial consonant or consonant cluster of a name is replaced with [b], [f] and [m]. Although [Cw] clusters are replaced as a whole, in apparent [Cj] clusters, the C alone is replaced, with the [j] remaining (3.34).

It would be interesting to test names like Ruth, where the initial consonant cannot cluster with [j]; if Name Game alternation produced [bjuθ], [fjuθ] and [mjuθ] rather than [buθ], [fuθ] and [muθ], this might instead suggest a productive process of j-Insertion. In the absence of such evidence, we must concur with Davis and Hammond (1995: 170) that `Cw clusters pattern like true onset clusters and Cy clusters do not'.

Again, however, the situation is not clear-cut. Recall that evidence from speech errors potentially supports analyses of /j/ both as an onset consonant and as nuclear. Different data involving co-occurrence restrictions similarly seem to support different approaches: although Davis and Hammond invoke homorganicity constraints in support of a nuclear account, strong evidence against a diphthongal analysis of [jū] comes from the relationship of phonotactics and syllable structure. Selkirk (1982b: 339) notes that one of the primary motivations for separating onset from rhyme and nucleus from coda, is the presence of phonotactic restrictions. For English at least,

it is within the onset, peak and coda that the strongest collocational restrictions obtain, [since] the likelihood of the existence of phonotactic constraints between the position slots in the syllable ... is a reflection of the immediate constituent (IC) structure relation between the two slots: the more closely related structurally ... the more subject to phonotactic constraints two position slots are.

Selkirk alleges that English has no phonotactic restrictions between onset and nucleus. This claim would be refuted by the proposed diphthong /ɪu/, since the [j], or [ɪ] segment is permissible only after certain onset consonants: after /r/, /w/, /ʃ/ and /ʤ/, for instance, [ū] surfaces alone, without [j]. These distributional restrictions are easily explicable if [j] is an onset consonant, since phonotactic constraints within the onset are, Selkirk suggests, to be expected, and any rule inserting /j/ will simply not be permitted to contravene these phonotactic restrictions. But they are hard to account for if [j]/[ɪ] is nuclear, since we will then be faced with a situation where a single vowel is distributionally restricted on the basis of the preceding onset consonant(s).

Davis and Hammond address problems of this sort, as well as some difficulties with their Pig Latin data, by proposing, as Shattuck-Hufnagel (1986) and Borowsky (1990) also suggest, that /j/ `moves' during the derivation from being closely bound to the /ū/ vowel to associating more regularly with other onset consonants: the underlying /Iu/ diphthong is affected by an /I/-to-[j] rule. Davis and Hammond argue that /Iu/ can follow coronals underlyingly, as one would expect of a vowel; however, if a coronal ends up in the same onset as the resyllabified onglide, the onglide will be deleted by rule as the cluster contravenes the phonotactics.

I shall adopt Davis and Hammond's nuclear analysis of the onglide in [jū] in what follows, with some revisions which will be detailed below. Some further evidence from alternations like reduce ~ reduction and study ~ studious, which lack [j] in some American English, strongly supports a diphthongal analysis, at least underlyingly. Furthermore, given the constraints on my model of Lexical Phonology, I have no choice but to disallow a j-Insertion analysis in the majority of forms. Allowing j-Insertion in underived cube, assume, reduce and venue would mean exempting it from DEC and the Alternation Condition. Furthermore, having the same underlying vowel in cute and cool, or dew and do, requires either absolute neutralization (as in Halle and Mohanan 1985), or an unacceptable level of exception-marking to stop cool, do and many others from undergoing j-Insertion (as in McMahon 1990). The exception rate will be high even if we account separately for restrictions on whole classes of preceding consonants, such as coronals in American English, using filters, and will be even higher in Scottish English, where there is no [ʊ], and look, put, wood have [u].

I will continue to transcribe the [jū] sequence as /jū/ underlyingly, to indicate that it is, exceptionally for English, a rising diphthong; and to highlight the fact that [j] does end up in the onset, as indicated by its palatalization of preceding consonants in duke [ʤūk], issue [ɪʃū] and Scots student [ʃtʃudn?], Hughie [çui]. Indeed, since I assume that different speakers may have different underlying representations and derivations, it is likely that restructuring will have affected these forms in some grammars, shifting them from the diphthongal class to underlying /ū/ with a preceding palatal consonant. Davis and Hammond also regard their /Iu/ diphthong as monomoraic; however, they require very wide spread late lengthening, since so many of the reflexes of the vowel are long. It seems more appropriate to assume shortening under low stress than the reverse, to account for the fact that the final vowel in venue and avenue tends to be shorter or laxer than [jū] in cube, and similarly that ambiguous and tabular have shorter medial vowels than ambiguity. One might therefore adopt in essence Rubach's (1984: 49) proposal that a rule of u-Laxing operates whenever /ū/ is unstressed, although this process might be better formulated as shortening /ū/ while leaving it tense; on the other hand, this may be an automatic, low-level phonetic process, not requiring a specific phonological rule. The /jū/ diphthong then also accords with the usual tendency of English diphthongs to pattern with long vowels.

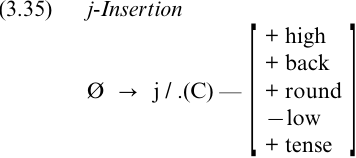

I assume, then, that non-alternating [ʊ] in push, put, etc., will be derived from /ʊ/; non-alternating [Λ] in pun, but words, and the [Λ]~[jū] alternation in study ~ studious and sulphur ~ sulphuric from /n/; and reduce ~ reduction, cube, venue, and ambiguous from /jū/. I retain a rule of j-Insertion (3.35), applying in a very restricted set of alternating forms, including studious (~ study) and tabular, angular (~ table, angle). As we shall see, Vowel Shift also plays a part in the derivation of some of these alternations. This may seem an unacceptably mixed analysis, involving as it does both a novel underlying diphthong, and an inserted glide; however, I shall show that our Lexical Phonological constraints delimit derived from surface-true cases.

We need not dwell on put, pull, pun, but, ambiguous, ambiguity, cube and venue words further; where there is no alternation, the underlying vowel will simply be surface true. j-Insertion and Vowel Shift will be restricted to alternating forms, and I therefore turn to the three types of alternation involving [jū], namely reduce ~ reduction, where the derived form contains a laxing context; study ~ studious, where tensing occurs in the derived form; and tabular, angular (~ table, angle).

Let us take the most straightforward case (though the one with most alternative derivations) first. Some speakers may not relate table and tabular, or angle and angular, productively; they will simply be listed independently, with underlying and lexical representations identical as befits non-alternating forms. For speakers who do derive tabular and angular, the inserted vowel might be /ū/: this vowel insertion will follow morphological derivation, and will in turn feed j-Insertion. Alternatively, the diphthong /jū/ might be the vowel inserted, with non-syllabic /j/ migrating later to the onset. Both options may be right, for different speakers. Furthermore, neither account is out of line with Davis and Hammond (1995) who, although in general discounting j-Insertion, do propose glide epenthesis for precisely these forms (1995: 179, fn.10). In the same footnote, they explicitly exclude reduce ~ reduction and study ~ studious from their investigation, given that these vowel alternations are post-coronal and [j] is therefore not involved for most American English.

We turn now to these reduce ~ reduction and study ~ studious alternations, which are slightly more complex, partly because English dialects fall into two sets here, those with /Λ/ and those without it. In Northern and North Midland dialects of England, for instance, [ʊ] appears in all non-alternating words in which RP would have [ʊ] or [Λ], and also replaces [Λ] in alternating forms like those in the right-hand column of (3.36).

In these varieties, underlying /jū/, which surfaces unchanged in reduce, will simply undergo-CC Laxing in reduction to give [ʊ]. Conversely, the underlying stem vowel for study ~ studious will be /ʊ/, the surface vowel of underived study, which will undergo CiV Tensing in studious to give [ū], with tensing feeding j-Insertion (3.35). In SPE and subsequent work (see especially Rubach 1984: 32, 40) the rule of CiV Tensing is restricted to non-high vowels; and /ʊ/ is, of course, [+high]. However, it seems that high vowels are excluded in the literature solely on the basis of the front vowel: SPE gives examples only for /ɪ/, as shown in (3.37).

In all probability, /ʊ/ as well as /ɪ/ was excluded from the scope of CiV Tensing, by the addition of the specification [-high], simply on the grounds of economy; tensing of /ʊ/ was achieved in SPE by a special tensing and unrounding rule designed to produce [ɨ̄], so that applying CiV Tensing to /ʊ/ was never necessary. Since there is no empirical reason for excluding /ʊ/ from CiV Tensing, I propose that the rule should be applicable to all vowels save /ɪ/.

An analysis deriving study ~ studious from /ʊ/ and reduce ~ reduction from /jū/ can, then, account for dialects which lack /Λ/. However, my analysis predicts that these Northern dialects represent the unmarked case, whereas in reality a relatively small proportion of English dialects lack /Λ/; in RP, Scots/SSE and many (if not all) American English dialects, [Λ] alternates with [(j)ū] while /ʊ/ never participates in morpho-phonemic alternations. Historically, of course, the Northern dialects with /ʊ/ but no /Λ/ do represent the unmarked case, in that they are typical of the Middle English situation; orthoepical evidence for (probably allophonic) lowering and unrounding of /ʊ/ to[Λ], with [ʊ] retained between a labial and another consonant, as in pull, push, woman and wood, first becomes available around 1640 (Dobson 1957: 93). Dobson attributes the retention of [ʊ] after labials to the lip position of /w p b f/ acting against the lip spreading required for [Λ]; however, he notes that `the rounding influence acted sporadically and produced inconsistent results, as is evident from the common words put, but, butcher and butter' (1957: 196). This eventually led to a phonemic split of /ʊ/ and /Λ/, since `the PresE distinction between words with [ʊ] and words with [Λ] shows no regularity; [Λ] occurs in positions that should favor [ʊ] in wonder, pun, puff ...but, bulk and bulb' (Dobson 1957: 196).

Dialects with /Λ/, such as RP, Scots/SSE (which, conversely, lack /ʊ/) and GenAm, are therefore historically more complex than the Northern English dialects, having undergone an additional sound change and innovated an extra phoneme, /Λ/. The synchronic picture is concomitantly more complex in these innovating varieties.

Working on our assumptions up to now, we diagnose the underlying vowel in study and studious as lax /Λ/, which surfaces unaltered in study but will undergo CiV Tensing in studious. In reduce ~ reduction, the underlier will be /jū/, with-CC Laxing in the derived form. However, tensing and laxing cannot be the whole story, since we also find differences in vowel height. In order for j-Insertion to operate in studious, we need raising as well as tensing to give the required [ū] (and this will be so even in American varieties where j-Insertion is not applicable); conversely, in reduction, we must account for the non-surfacing of /j/ and the vowel lowering.

The process which first comes to mind when considering a Modern English alternation involving tense and lax vowels of differing heights is, of course, Vowel Shift. As we saw above, Jaeger (1986: 86) argues that the derivation of alternations using the synchronic VSR no longer depends solely on which vowel pairings resulted from the Great Vowel Shift (and [(j)ū]~[Λ] did not); instead, Modern English speakers are influenced by the frequency of alternations and their conformity with the English Spelling Rule. Consequently, certain alternations like [ū]~[ɒ] and [aʊ] ~ [Λ], which were originally derived via Vowel Shift, are no longer perceived as part of the Vowel Shift set.

I contend that the opposite also holds: as the motivation for Vowel Shift changes, it not only comes to exclude alternations which were included earlier, but also to include alternations which did not involve the historical Great Vowel Shift. This is the case with [(j)ū]~[Λ], which is historically an alternation of tense and lax vowels of the same height, complicated by the subsequent lowering of /ʊ/ in some dialects. As a relatively frequent alternation, with both elements commonly spelt <u>, involving a tense and a lax vowel of different heights, [(j)ū]~[Λ] could easily conform to an internalized Vowel Shift template. Indeed, psycholinguistic evidence (Jaeger 1986, Wang and Derwing 1986) suggests that this is the case: data from Jaeger's experiment in(3.14)above showed that speakers produced on average 75 per cent affirmative responses to this alternation, close to the 80-93 percent for the four core alternations on which they had been trained, and well above the maximum 25 per cent affirmative response for vowel pairs to which they had been trained to respond negatively. It seems that synchronic phonological rules need not, and perhaps cannot be identical to their historical sources in a constrained lexical model. In dialects without /Λ/, VSR will be irrelevant to the derivation of [jū]~[ʊ],presumably because an alternation must involve two surface vowels of different heights to be included in the Vowel Shift concept.

However, although VSR will produce a quality difference here, it will not alone produce quite the right quality difference; recall that the innovation of/Λ/has disrupted the system. In varieties with /Λ/, the [(j)ū] ~[Λ] alternation will therefore involve VSR and two Level 1 Rounding Adjustment rules; tensed [Λ̄]will round to[ō], which then shifts to[ū]via V̄SR in studious, while laxed [ʊ] will shift to [o] and subsequently unround to[Λ] in reduction, assumption. In accents lacking /Λ/, /ʊ/will be exempted from V̄SR and the derivation of reduce, reduction, study and studious will be as shown in (3.38a), using only the tensing and laxing rules. In other varieties, /ʊ/will be permitted to undergo V̄SR, and/Λ/ need not be explicitly excluded either, since it will never appear in the correct context for shifting to occur, being itself derived via V̄SR in reduction and assumption. Derivations are shown in (3.38b).

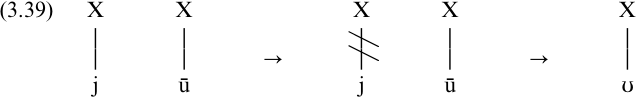

So far, so good; but the puzzle still has one missing piece. j-Insertion, in its now severely limited role, will supply [j] in studious (and for some speakers, in angular, tabular). However, we are assuming underlying /jū/ in reduce ~ reduction, and here [j] fails to surface in the derived form. This is not a problem for American English, where the underlier will be monophthongal /ū/; but for other varieties, where [j] is permissible after coronals, we might require some filter or repair strategy, reflecting the absence of [j] before [Λ]. In fact, this is not necessary, given the argument for underlying diphthongs. Recall that the divine ~ divinity alternation was there derived from underlying /aɪ/. I argued that, as part of laxing, this diphthong lost its less prominent part, here the offglide, as shown in (3.11). If we extend this analysis to the diphthong /jū/, the onglide will drop and the remaining vowel lax, as shown in (3.39).

Not only does this analysis remove the requirement for specific deletion of /j/; it also indicates that /jū/, although its prominence pattern is uncharacteristic, patterns in terms of laxing with the other English diphthong involved in synchronic Vowel Shift alternations. This does seem to support Davis and Hammond's (1995) contention that /j/ in this sequence is initially nuclear.

In summary, I give sample derivations in (3.40) for [Λ], [ʊ], [ū]and[jū] words, excluding the reduce ~ reduction and study ~ studious alternations which appear in (3.38) above, indicating the much reduced distance between underlying and surface forms as compared with any analysis.