Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Past Simple

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Passive and Active

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Grammar Rules

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Semantics

Pragmatics

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

An outline

المؤلف:

APRIL McMAHON

المصدر:

LEXICAL PHONOLOGY AND THE HISTORY OF ENGLISH

الجزء والصفحة:

P215-C5

2024-12-24

88

An outline

Before assessing the numerous challenges to underspecification posed in a diverse range of phonological models, and examining why its effects are particularly pernicious in LP, we must explore the alleged advantages which have led to its becoming an expected ingredient of phonological theory in the first place.

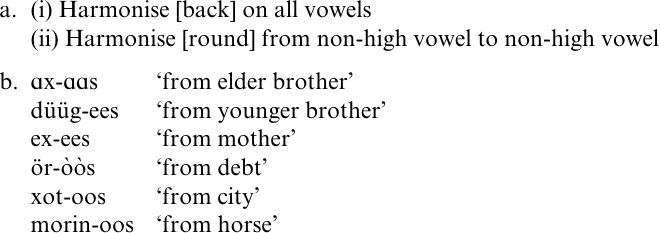

Underspecification theory (Archangeli 1984, 1988; Kiparsky 1982, 1985) is based squarely on the Standard Generative evaluation metric, which values grammars highly if they mark only idiosyncratic properties at the underlying level, filling in predictable features using rules and conventions. It therefore rests, like the identity hypothesis, on the assumptions that grammars in general, and underlying representations in particular, should be maximally economical, and that computation is favored over storage. Underspecification presupposes neutralization, markedness and the elimination of redundancy; and the main application of the theory so far has been in the domain of autosegmental analyses of harmony processes and feature spreading. For instance, Steriade (1979) discusses Khalkha Mongolian vowel harmony (see (1)).

(1)

The high round vowels [u] and [ü] are opaque to rounding; they are not themselves affected, and do not allow the feature to spread to their right. However, high unrounded [i], although not subject to rounding harmony, is transparent to the spreading rule, as shown by morinoos. Steriade proposes that only initial vowels should be specified for the features [back] and [round]; these values will spread throughout the word. However, [u] and [ü] will also be marked as [+ round], to show their status as opaque vowels; the spreading process will be blocked by this existing specification. A default rule will later assign [- round] to those underspecified vowels unaffected by rounding harmony, including [i] and any vowel following [u] or [ü].

This sort of argument represents a persuasive way of handling feature spreading. However, underspecification has been extended to other domains in two main ways, leading to the subtheories of contrastive specification and radical underspecification: although I shall present these individually here, it should be noted that the line between them is not always obvious (Goldsmith 1990: 243).

Contrastive specification, the less extreme application of underspecification theory, follows from the earlier notion of redundancy and deals uniquely with non-distinctive features, which are hypothesised to have the single underlying specification [0F]. For example, sonorants in English are all voiced, making voicing non-distinctive for this class of sounds; the underlying representations of sonorants would therefore contain the underspecified value [0 voice], with [+ voice] filled in subsequently by a redundancy rule. Radical underspecification, on the other hand, extends also to distinctive features: its focus is not contrastivity, but predictability. Radical underspecification is more strongly directed towards the achievement of simplicity than contrastive specification, and is motivated by the Feature Minimization Principle (2).

(2) Feature Minimisation Principle (Archangeli 1984: 50):

`A grammar is most highly valued when underlying representations include the minimal number of features necessary to make different the phonemes of the language.'

For instance, while English sonorants are uniquely voiced, obstruents surface as contrastively voiced or voiceless. However, radical under specification requires us to mark either [+ voice] or [- voice] under lyingly; let us select [+ voice]. Obstruents which surface as voiceless will be underlyingly [0 voice], with a default rule filling in the appropriate specification during the derivation.

In this case, the default rule is arguably universal, since obstruents are cross-linguistically more frequently voiceless than voiced. However, values can also be supplied by ordinary language specific phonological rules. For instance, Trisyllabic Laxing changes the long, tense initial vowel of divine to short and lax in divinity; but it could also operate in a structure-building rather than a structure-changing way to supply the specifications [- tense] and [- long] (or single-attachment) for the first vowel of words like sycamore, which could then be left unspecified for these features at the underlying level. Since the rule manipulates contrastive features, it does not violate Structure Preservation; and since the DEC affects only structure-changing applications, it will not affect TSL here, although it will block laxing of vowels with an underlying [+ tense] specification in an underived environment, removing one of the major objections to earlier blank-filling analyses raised by Stanley (1967). Stanley also asserted that the option of having [0F] as well as [+F] and [-F] at the underlying level really converts binary features into ternary ones; but Kiparsky (1982) argues that this does not apply in a lexicalist model of underspecification, where in any environment, only the marked specification /+F/ or /-F/, and the unmarked specification /0F/, will be allowed. The picture is further complicated by the existence of two different versions of radical underspecification (Mohanan 1991): the context-sensitive variety, as adopted by Kiparsky, holds that both values of a feature cannot be specified in the same environment, while Arch angeli's context-free radical underspecification makes the prediction that only one value may be marked underlyingly in any environment.