Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Clauses

Part of Speech

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Direct and Indirect speech

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

The ordering of SVLR and LLL in a Lexical Phonology

المؤلف:

APRIL McMAHON

المصدر:

LEXICAL PHONOLOGY AND THE HISTORY OF ENGLISH

الجزء والصفحة:

P191-C4

2024-12-20

1346

The ordering of SVLR and LLL in a Lexical Phonology

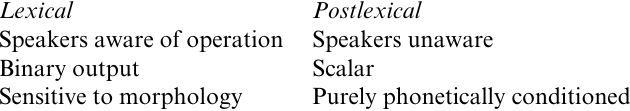

Various criteria for distinguishing lexical from postlexical rule applications are suggested by, for instance, Kiparsky (1982) and Mohanan (1982, 1986); a subset is given in (1).

(1)

Although, as we saw, there is reason to believe that the divide between lexical and postlexical rule applications is more of a cline than a rigid and unbridgeable division, there is some support for these criteria. For instance, although some postlexical rule applications, such as glottalling in English, are markers or even stereotypes, most are automatic phonetic processes, like aspiration of voiceless stops in English, and native speakers fail to observe their effects. It seems that LLL meets this criterion; according to Delattre (1962: 1142) `Some speakers will make a distinctive difference of length between bomb and balm, but they will make a larger difference of length - though non-distinctive - between leap and leave. And the naive subject will easily be made conscious of the first difference of length but not the second.'

However, Scots/SSE speakers do seem to be generally aware of the differences produced by SVLR (or can easily be made aware of them). SVLR thus appears to control a binary, categorizable distinction of length; LLL, on the other hand, increases the duration of long and short vowels by a variable amount, depending on the nature of the following consonant: its output is therefore essentially non-binary.

Mohanan's major criterion for distinguishing between lexical and postlexical rules involves sensitivity to the morphology: `A rule application requiring morphological information must take place in the lexicon' (1986: 9). LLL might initially seem to be lexical by this criterion, since sensitivity to morphological information would include sensitivity to the presence of boundaries, and vowels are lengthened word-finally. However, it seems that LLL affects vowels utterance-finally, or prepausally, rather than word-finally; if pauses are inserted after syntactic concatenation (Mohanan 1982), any rule referring to the position of pauses is necessarily postlexical. SVLR, on the other hand, is clearly sensitive to morphological information, and indeed a boundary is included in its structural description. SVLR lengthens vowels word finally, but also before regular inflections, even when the consonant following the boundary is not itself a lengthening context; the vowel is therefore lengthened in sees [si:z] and keyed [ki:d], and in brewed and tied but not brood and tide.

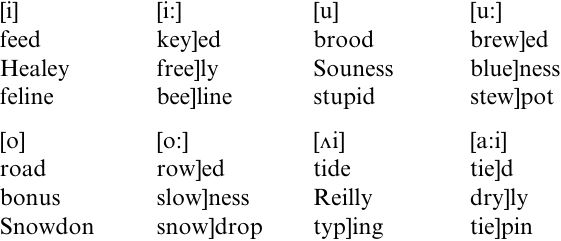

LLL can therefore be classified as clearly postlexical, and SVLR as tenuously lexical. SVLR operates when the affected vowel is stem-final and in a Class II derived or regularly inflected form, or in the first stem of a compound, but not in morphologically underived forms with similar phonological contexts; relevant data (from Harris 1989) are shown in (2). I argued that Class II derivation, regular inflection and compounding all take place on Level 2; so must SVLR.

(2)

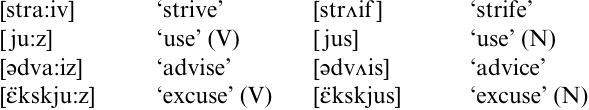

Carr (1992) presents three types of evidence which may indicate that SVLR also applies on Level 1. First, in Scots and SSE the vowel in ablaut past tense forms like rode, strode (as opposed to road) is long: Carr argues that Level 1 ablaut rules, in the style of Halle and Mohanan (1985) provide a derived environment for lengthening in these cases. Secondly, Noun Plural Fricative Voicing is said to feed SVLR on Level 1, in life ~ lives, leaf ~ leaves and hoof ~ hooves. Finally, Carr cites the cases in (3), from Allan (1985).

(3)

The ablaut and Noun Plural Fricative Voicing examples are variable, and a pattern of length attributable to SVLR is only observable for some speakers; this, however, is what one might expect of Level 1 rules, which seem to control alternations mid-way between the fully productive and the fully lexicalized.

Carr (1992) argues that, although SVLR applies at Level 1 in ablaut past tenses and Noun Plural Fricative Voicing cases; in general lengthening takes place precyclically on Level 2, before affixation. Thus, in row, rowed, SVLR applies at Level 2 in open syllables: Carr (1992) prefers this context to the following boundary ] assumed above since his version will include cases like spider, pylon, where McMahon (1991) has to assume reanalysis with a `false' morpheme boundary for those speakers with lengthened vowels.

However, very little of Carr's evidence allows clear conclusions to be drawn on the level ordering of SVLR. First, I have argued above that ablaut past tenses in Modern English should not be derived by rule, even on Level 1; instead, all those outside the keep ~ kept class should be treated as having two lexical entries. In that case, forms like rode, strode do not constitute Level 1 derived environments for SVLR, and must be stored with a long vowel underlyingly. In historical terms, their long vowel is the result of analogy with regular past tense forms like rowed, snowed, which are eligible for SVLR on Level 2. I shall argue that this operation of analogy was partly responsible for the extension of SVLR from Level 2 to Level 1; and indeed, this account predicts that for some time, when ablaut was still a semi-productive process, it would have fed SVLR in these forms on Level 1. Now, however, we have fossilized and stored alternations, and part of that storage involves the vowel length historically attributable to SVLR. Carr (1992: 104±5) claims that invoking analogy in this way is non explanatory, and tantamount to accepting that SVLR does apply in these forms. I disagree: it is tantamount to accepting that SVLR did apply in these forms, when its conditions were met by the application of a preceding process on Level 1. The demise of that process for Modern English speakers means that although the effects of historical SVLR are still discernible in cases like rode, they are now part of a learned alternation. Anderson (1993: 425) also points out that ablaut per se cannot be responsible for feeding SVLR in these cases, as Carr claims, since lengthening takes place only before the past tense marker-d (and not in wrote, therefore). Since SVLR in regular past tenses always involves a vowel-final stem, which in the normal course of events will attract a following past marker-d, this supports my proposal of analogy between rowed and rode, rather than a (semi-) productive connection with ablaut.

Secondly, and perhaps surprisingly, Carr does not use Allan's (1985) evidence in (3) above to support his proposal of Level 1 SVLR. Allan argues that the advise ~ advice cases represent Verb to Noun zero derivation, which according to Kiparsky (1982) is a Level 1 process. However, if this is so, Carr's precyclic SVLR would counterfactually lengthen both forms. Carr is therefore forced to analyze these as denominal zero derivations, which Kiparsky (1982) assigns to Level 2; but his only grounds for so doing are that half ~ halve and mouth ~ mouthe `look more plausibly like cases of N ? V zero derivation', and that this can automatically be extended to the advise ~ advice alternations. Even so, Carr must then allow SVLR to apply on Level 2 in open syllables, and on Levels 1 and 2 before voiced continuants, the only apparent advantage being the lack of reference to ]. But again, there are two objections. Carr's assumption of open-syllable SVLR does not seem well motivated: there are speakers who lengthen the vowel in pylon, spider, but equally there are others who do not, and yet another group who lengthen one but not the other. The evidence above from Milroy (1995) on SVLR in Newcastle and Donegan (1993) on Canadian Raising also suggest that exceptionally long and short diphthongs occur fairly frequently, and that perhaps a split of /Λi/ from /ai/ is in progress. Furthermore, the use of ] in phonological rules reflects the interaction of morphology and phonology which is central to LP: of course it is important to allow for purely phonological conditioning, but it is equally vital to recognize cases where morphological factors are paramount, and allow the phonology to refer to these. I shall argue in 4.6 that the historical reanalysis of SVLR from LLL necessarily involves both analogy and reference to ], and that the incipient contrast of /Λi/ and /ai/ is also central to the continued development of SVLR. I therefore maintain the formulation of SVLR suggested in (The environment for SVLR (5)): SVLR will apply on Levels 1 and 2; but in the former case, will be restricted by the Derived Environment Condition.

الاكثر قراءة في Phonology

الاكثر قراءة في Phonology

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)