Underspecification in Lexical Phonology

If underspecification is increasingly recognized as problematic regardless of phonological model, it is several degrees of magnitude worse in Lexical Phonology. As we have seen, many of the strategies encouraging abstract analyses in SGP, typically involving free rides and distant underliers, are disfavored or prohibited in LP, meaning that underlying representations have generally been approximated to surface forms. It is hard to resist the temptation to see underspecification as an alternative strategy for reintroducing abstractness.

For instance, different degrees of underspecification involve different degrees of departure from the optimal lexicalist analysis of dialect distinctions. As we saw in (Length, tenseness and English vowel systems(2)), an analysis of RP and Scots/SSE on their own terms reveals substantial underlying differences: while RP vowels are variably short or long and lax or tense, tenseness alone is relevant at least for core varieties of Scots, with all vowels underlyingly short and tense vowels lengthened during the derivation by SVLR.

If we introduce contrastive specification, the situation does not change dramatically, and the underlying differences remain. In RP, only tense ness or length need be distinctive: I select length as underlyingly contrastive, for the reasons given in (Length, tenseness and English vowel systems(2)) (see also Lindsey 1990). If all RP vowels are specified as either long or short and as [0 tense] underlyingly, some redundancy rule must subsequently fill in the appropriate values. Archangeli (1988) holds that such redundancy rules should operate as late as possible in the derivation, and this is reinforced in LP by Structure Preservation, which restricts rules mentioning non-distinctive features to the postlexical component. This may be problematic in the present case, since although tenseness is non-contrastive, a number of severe derivational difficulties arise if it cannot be referred to in the lexicon; Halle and Mohanan (1985), for instance, claim that [± tense] is not underlyingly distinctive but that various tensing rules must nonetheless apply lexically. There might be two ways around this: Borowsky (1990) assumes that Structure Preservation is operational only on Level 1; and Kiparsky's (1985: 93) version of Structure Preservation implies that, if a rule introduces only unmarked specifications, it may operate lexically. If in the unmarked case for English, [+ tense] is associated with long and [- tense] with short vowels, a redundancy rule making this correlation may indeed be lexical, allowing length alone to be specified at the underlying level for RP, with [± tense] introduced early in the lexicon.

As far as Scots/SSE is concerned, contrastive specification will leave all (or at least most) vowels marked [0 long] underlyingly. They will, however, still be specified as [+ tense] or [- tense]. Length will be filled in by the SVLR for tense vowels before /r/, voiced fricatives and boundaries, while shortness will be supplied by a subsequent redundancy rule affecting tense vowels in non-lengthening contexts and lax vowels everywhere. Crucially, however, the feature bisecting the underlying vowel system of RP will still be length, while in SSE it will be tenseness.

If radical underspecification is introduced, this underlying difference can be made to vanish. In RP, underspecification will be extended to length. Vowels will either be specified underlyingly as [+ long] and [0 long], or as [- long] and [0 long] (or the autosegmentalized equivalents), with the missing value supplied partly by the lexical lengthening/tensing or shortening/laxing rules applying in a structure-building capacity, and partly by universal default rules. As far as tenseness is concerned, we can either retain the underlying specification of all vowels as [0 tense], or choose also to mark either [+ tense] or [- tense] at the underlying level, and assign the other by default rule.

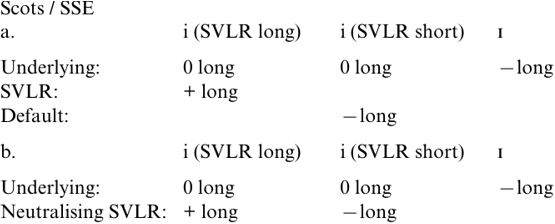

In Scots/SSE, we shall have to choose one value for length at the underlying level. If we assume that vowels are [- long] and [0 long] (ignoring those which surface as consistently long), we neatly characterize those vowels not subject to the SVLR, the former set. Those vowels specified [- long] will surface as consistently short, while those which begin as [0 long] will be marked as long before /r/, voiced fricatives and boundaries, and as short in other contexts. There are two ways of achieving this. First (see 1a), we could allow SVLR to specify vowels as [+ long] in lengthening contexts, then formulate a default rule to supply the value [- long] elsewhere.

(1)

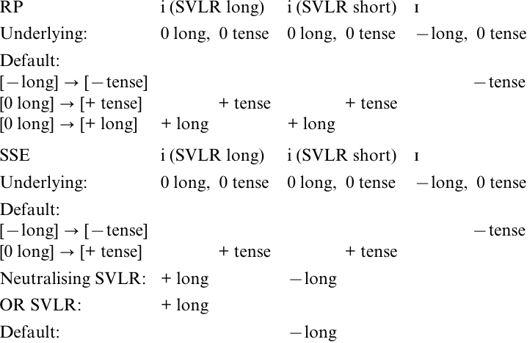

However, there is absolutely nothing to stop us from following another route, returning to a version of SVLR far closer to its historical formulation. On this analysis (1b), SVLR would be bipartite, assigning [+ long] before /r/, voiced fricatives and boundaries, and [- long] elsewhere. As a structure-building rule, SVLR could apply on Level 1 of the lexicon, despite the DEC. There might ostensibly be a problem with Structure Preservation, which is intended to stop lexical rules from referring to non-distinctive features; but since the definition of `non-distinctive' adopted in the literature on underspecification involves lack of specification at the underlying level, and since this analysis assumes that vowels are underlyingly [- long] or [0 long], which is quite as specified as any underlying feature can be, I fail to see how Structure Preservation or anything else can rule this out. As for tenseness, this can be treated in either of the ways suggested above for RP: vowels could be specified as [0 tense] and either [+ tense] or [- tense], with a default rule supplying the missing value, or all vowels could begin as [0 tense], with some combination of universal principles and language-specific rules conspiring to assign [- tense] by redundancy rule to /ɪ ε Λ/ and [+ tense] to everything else. If we pursue the option of introducing [± tense] by redundancy rule very early in the lexicon, before the operation of SVLR, [+ tense] might be correlated with [0 long] vowels and [- tense] with [- long] ones. (2) gives a possible derivation along these lines for RP and SSE.

(2)

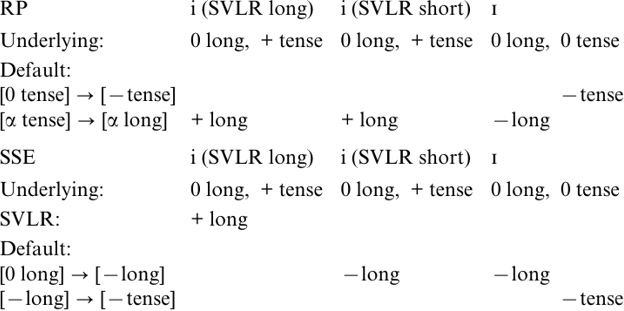

Nor are these the only options in a radically underspecified Lexical Phonology. For instance, we could also analyze SSE as having [+ tense] and [0 tense] but only [0 long] underlyingly, with a lengthening-only version of SVLR affecting tense vowels in lengthening environments and default rules supplying [- tense] and [- long] later. This would keep the synchronic SVLR more strictly distinct from its historical predecessor. However, it would not necessarily maintain the difference between RP and SSE at the underlying level, since we can easily approximate RP to SSE, with [+ tense], [0 tense] and [0 long] and two default rules, one supplying [- tense] and the other correlating length with [+ tense] and shortness with [- tense] (see (3)): this equally may not be the best account, but it is certainly a possible one, and may demonstrate that whatever analysis we select for one of the dialects, we can apply to the other.

(3)

It follows that, in a Lexical Phonology with radical underspecification, we can maintain the dialect identity hypothesis of SGP; and although the bipartite synchronic SVLR of the underspecification analysis does not strictly mirror its historical counterpart, this is purely by virtue of its structure-building rather than structure-changing function. The general motivation for structure-building rules was questioned in the previous section. At the very least, the bipartite SVLR is far closer than the lengthening-only version to its historical antecedent; and this again may represent a step backwards, retarding the reflection of historical developments in the synchronic grammar. A neutralizing SVLR was also rejected earlier on the grounds of learnability: it is not at all clear that the child would be better able to acquire the underspecified system, especially given the doubts raised by practitioners of underspecification over the learnability of any radically underspecified representation (Archangeli 1988: 193).

In short, there may be machinery in linguistic theory that leaves doors open for us which are better off closed. Radical underspecification may be one such piece of apparatus; and if so, it is not compatible with a highly constrained model of LP in which we wish to explore not only synchronic system design, but also dialect divergence and language change, and their impact on the rules and the underlying representations. Contrastive specification might be permitted to remain, perhaps limited to features which behave autosegmentally in a particular language, since it does not conflict so clearly with the constraints of LP, or with its relatively concrete assumptions on language acquisition.

However, we might want to go further than this and rule out under specification altogether, because it bleeds the constraints of LP, making their application opaque and their enforcement impossible. This is particularly noticeable from Borowsky (1990), who adopts Kiparsky's context-sensitive version of radical under specification. First, underspecification affects Structure Preservation. Borowsky (1990: 116) assumes that different partially specified underliers may merge on the surface once all features have been filled in. She also argues that Structure Preservation means no segment which is not a phoneme of the language can be derived on Level 1, where `if the segment /x/ is not a phoneme of English there is no occurrence of it, or a partially specified form of it, anywhere in the lexicon' (1990: 30). However, underspecification means this is hard to check: we would have to take all potentially eligible underlying segments, put them through all phonological and default rules, and see if /x/ is in fact derived (and if so, given Borowsky's contention that Structure Preservation switches off after Level 1, at what level).

Borowsky also uses underspecification to derive free ride effects. For instance, the Sanskrit ruki rule retroflexes /s/ after /r u k i/. In SGP, retroflexes in underived environments would have been derived from /s/ via a free ride through the ruki rule. In LP, the DEC would block such derivations; but if retroflexes are underlyingly unspecified for [retroflex], the ruki rule can apply in a structure-building capacity, evading the DEC and favoring what is essentially a diacritic analysis. In cases of Velar Softening, Borowsky marks non-softening velars as underlyingly [+ back] and softening ones as [0 back], allowing Velar Softening to supply [- back] in underived accident as well as derived criticism; this again is a clear notational variant of the SPE use of /kd gd/ for softening velars. Similarly, Borowsky reanalyses those rules which Halle and Mohanan (1985) restricted by fiat to Level 2, as blank-filling operations on Level 1.

Borowsky (1990: 73) notes that we can stop rules from applying in underived environments; but `This is simply to miss a generalization from my point of view.' She also argues that an analysis using two rules instead of one `is not quite in the spirit of our enterprise' (1990: 94). But these are not arguments: they are restatements of the assumptions of SGP, which do not sit easily with the constraints and limitations of LP. In a constrained model, the constraints effectively choose our analyses for us, but if we allow underspecification, it almost always allows these constraints to be circumvented. Borowsky's conclusion from this is that we should abandon the Strict Cyclicity Condition (our Derived Environment Condition), since `the use of underspecification removes many classic cases which motivated the SCC' (1990: 28). Logically, this can be interpreted as an argument against either the SCC or underspecification: although underspecification is now frequently associated with LP, it `can in principle be accepted or rejected independently of the other ideas of lexical phonology' (Goldsmith 1990: 243). The arguments presented here lead me to favor a version of LP which retains the DEC and rejects underspecification. Since underspecification permits analyses which would otherwise be ruled out, and is incompatible with the reduction of abstractness and coherence with external evidence characteristic of a lexicalist model, I conclude, to misquote Borowsky (1990: 94), that it `is not quite in the spirit of our enterprise'.

الاكثر قراءة في Phonology

الاكثر قراءة في Phonology

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة