تاريخ الفيزياء

علماء الفيزياء

الفيزياء الكلاسيكية

الميكانيك

الديناميكا الحرارية

الكهربائية والمغناطيسية

الكهربائية

المغناطيسية

الكهرومغناطيسية

علم البصريات

تاريخ علم البصريات

الضوء

مواضيع عامة في علم البصريات

الصوت

الفيزياء الحديثة

النظرية النسبية

النظرية النسبية الخاصة

النظرية النسبية العامة

مواضيع عامة في النظرية النسبية

ميكانيكا الكم

الفيزياء الذرية

الفيزياء الجزيئية

الفيزياء النووية

مواضيع عامة في الفيزياء النووية

النشاط الاشعاعي

فيزياء الحالة الصلبة

الموصلات

أشباه الموصلات

العوازل

مواضيع عامة في الفيزياء الصلبة

فيزياء الجوامد

الليزر

أنواع الليزر

بعض تطبيقات الليزر

مواضيع عامة في الليزر

علم الفلك

تاريخ وعلماء علم الفلك

الثقوب السوداء

المجموعة الشمسية

الشمس

كوكب عطارد

كوكب الزهرة

كوكب الأرض

كوكب المريخ

كوكب المشتري

كوكب زحل

كوكب أورانوس

كوكب نبتون

كوكب بلوتو

القمر

كواكب ومواضيع اخرى

مواضيع عامة في علم الفلك

النجوم

البلازما

الألكترونيات

خواص المادة

الطاقة البديلة

الطاقة الشمسية

مواضيع عامة في الطاقة البديلة

المد والجزر

فيزياء الجسيمات

الفيزياء والعلوم الأخرى

الفيزياء الكيميائية

الفيزياء الرياضية

الفيزياء الحيوية

الفيزياء العامة

مواضيع عامة في الفيزياء

تجارب فيزيائية

مصطلحات وتعاريف فيزيائية

وحدات القياس الفيزيائية

طرائف الفيزياء

مواضيع اخرى

First principles of quantum mechanics

المؤلف:

Richard Feynman, Robert Leighton and Matthew Sands

المصدر:

The Feynman Lectures on Physics

الجزء والصفحة:

Volume I, Chapter 37

2024-04-20

1832

We will now write a summary of the main conclusions of the main quantum's experiments. We will, however, put the results in a form which makes them true for a general class of such experiments. We can write our summary more simply if we first define an “ideal experiment” as one in which there are no uncertain external influences, i.e., no jiggling or other things going on that we cannot take into account. We would be quite precise if we said: “An ideal experiment is one in which all of the initial and final conditions of the experiment are completely specified.” What we will call “an event” is, in general, just a specific set of initial and final conditions. (For example: “an electron leaves the gun, arrives at the detector, and nothing else happens.”) Now for our summary.

Summary

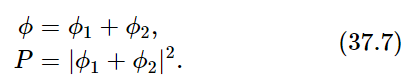

1- The probability of an event in an ideal experiment is given by the square of the absolute value of a complex number ϕ which is called the probability amplitude:

2- When an event can occur in several alternative ways, the probability amplitude for the event is the sum of the probability amplitudes for each way considered separately. There is interference:

If an experiment is performed which is capable of determining whether one or another alternative is actually taken, the probability of the event is the sum of the probabilities for each alternative. The interference is lost:

One might still like to ask: “How does it work? What is the machinery behind the law?” No one has found any machinery behind the law. No one can “explain” any more than we have just “explained.” No one will give you any deeper representation of the situation. We have no ideas about a more basic mechanism from which these results can be deduced.

We would like to emphasize a very important difference between classical and quantum mechanics. We have been talking about the probability that an electron will arrive in a given circumstance. We have implied that in our experimental arrangement (or even in the best possible one) it would be impossible to predict exactly what would happen. We can only predict the odds! This would mean, if it were true, that physics has given up on the problem of trying to predict exactly what will happen in a definite circumstance. Yes! physics has given up. We do not know how to predict what would happen in a given circumstance, and we believe now that it is impossible, that the only thing that can be predicted is the probability of different events. It must be recognized that this is a retrenchment in our earlier ideal of understanding nature. It may be a backward step, but no one has seen a way to avoid it.

We make now a few remarks on a suggestion that has sometimes been made to try to avoid the description we have given: “Perhaps the electron has some kind of internal works—some inner variables—that we do not yet know about. Perhaps that is why we cannot predict what will happen. If we could look more closely at the electron, we could be able to tell where it would end up.” So far as we know, that is impossible. We would still be in difficulty. Suppose we were to assume that inside the electron there is some kind of machinery that determines where it is going to end up. That machine must also determine which hole it is going to go through on its way. But we must not forget that what is inside the electron should not be dependent on what we do, and in particular upon whether we open or close one of the holes. So, if an electron, before it starts, has already made up its mind (a) which hole it is going to use, and (b) where it is going to land, we should find P1 for those electrons that have chosen hole 1, P2 for those that have chosen hole 2, and necessarily the sum P1+P2 for those that arrive through the two holes. There seems to be no way around this. But we have verified experimentally that that is not the case. And no one has figured a way out of this puzzle. So, at the present time we must limit ourselves to computing probabilities. We say “at the present time,” but we suspect very strongly that it is something that will be with us forever—that it is impossible to beat that puzzle—that this is the way nature really is.

الاكثر قراءة في ميكانيكا الكم

الاكثر قراءة في ميكانيكا الكم

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)