تاريخ الفيزياء

علماء الفيزياء

الفيزياء الكلاسيكية

الميكانيك

الديناميكا الحرارية

الكهربائية والمغناطيسية

الكهربائية

المغناطيسية

الكهرومغناطيسية

علم البصريات

تاريخ علم البصريات

الضوء

مواضيع عامة في علم البصريات

الصوت

الفيزياء الحديثة

النظرية النسبية

النظرية النسبية الخاصة

النظرية النسبية العامة

مواضيع عامة في النظرية النسبية

ميكانيكا الكم

الفيزياء الذرية

الفيزياء الجزيئية

الفيزياء النووية

مواضيع عامة في الفيزياء النووية

النشاط الاشعاعي

فيزياء الحالة الصلبة

الموصلات

أشباه الموصلات

العوازل

مواضيع عامة في الفيزياء الصلبة

فيزياء الجوامد

الليزر

أنواع الليزر

بعض تطبيقات الليزر

مواضيع عامة في الليزر

علم الفلك

تاريخ وعلماء علم الفلك

الثقوب السوداء

المجموعة الشمسية

الشمس

كوكب عطارد

كوكب الزهرة

كوكب الأرض

كوكب المريخ

كوكب المشتري

كوكب زحل

كوكب أورانوس

كوكب نبتون

كوكب بلوتو

القمر

كواكب ومواضيع اخرى

مواضيع عامة في علم الفلك

النجوم

البلازما

الألكترونيات

خواص المادة

الطاقة البديلة

الطاقة الشمسية

مواضيع عامة في الطاقة البديلة

المد والجزر

فيزياء الجسيمات

الفيزياء والعلوم الأخرى

الفيزياء الكيميائية

الفيزياء الرياضية

الفيزياء الحيوية

الفيزياء العامة

مواضيع عامة في الفيزياء

تجارب فيزيائية

مصطلحات وتعاريف فيزيائية

وحدات القياس الفيزيائية

طرائف الفيزياء

مواضيع اخرى

Initial conditions for Harmonic motion and circular motion

المؤلف:

Richard Feynman, Robert Leighton and Matthew Sands

المصدر:

The Feynman Lectures on Physics

الجزء والصفحة:

Volume I, Chapter 21

2024-03-09

1655

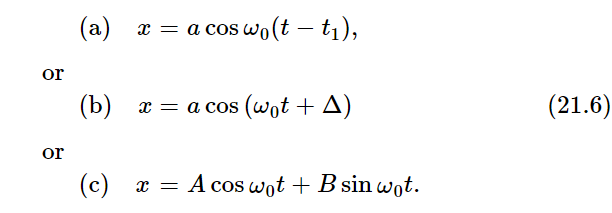

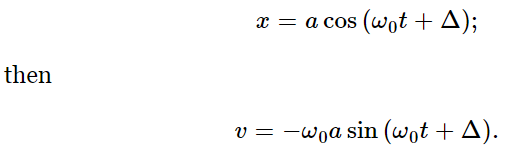

Let us consider what determines the constants A and B, or a and Δ. Of course, these are determined by how we start the motion. If we start the motion with just a small displacement, that is one type of oscillation; if we start with an initial displacement and then push up when we let go, we get still a different motion. The constants A and B, or a and Δ, or any other way of putting it, are determined, of course, by the way the motion started, not by any other features of the situation. These are called the initial conditions. We would like to connect the initial conditions with the constants. Although this can be done using any one of the forms (21.6), it turns out to be easiest if we use Eq. (21.6c).

Suppose that at t=0 we have started with an initial displacement x0 and a certain velocity v0. This is the most general way we can start the motion. (We cannot specify the acceleration with which it started, true, because that is determined by the spring, once we specify x0.) Now let us calculate A and B. We start with the equation for x,

Since we shall later need the velocity also, we differentiate x and obtain

These expressions are valid for all t, but we have special knowledge about x and v at t=0. So, if we put t=0 into these equations, on the left we get x0 and v0, because that is what x and v are at t=0; also, we know that the cosine of zero is unity, and the sine of zero is zero. Therefore, we get

From these values of A and B, we can get a and Δ if we wish.

That is the end of our solution, but there is one physically interesting thing to check, and that is the conservation of energy. Since there are no frictional losses, energy ought to be conserved. Let us use the formula

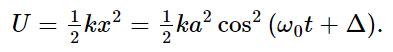

Now let us find out what the kinetic energy T is, and what the potential energy U is. The potential energy at any moment is 1/2 kx2, where x is the displacement and k is the constant of the spring. If we substitute for x, using our expression above, we get

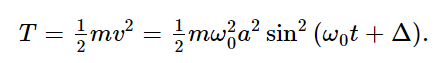

Of course, the potential energy is not constant; the potential never becomes negative, naturally—there is always some energy in the spring, but the amount of energy fluctuates with x. The kinetic energy, on the other hand, is 1/2 mv2, and by substituting for v we get

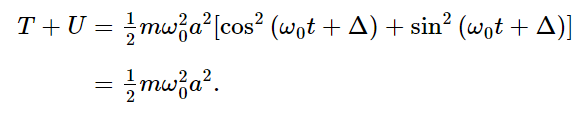

Now the kinetic energy is zero when x is at the maximum, because then there is no velocity; on the other hand, it is maximal when x is passing through zero, because then it is moving fastest. This variation of the kinetic energy is just the opposite of that of the potential energy. But the total energy ought to be a constant. If we note that k=mω20, we see that

The energy is dependent on the square of the amplitude; if we have twice the amplitude, we get an oscillation which has four times the energy. The average potential energy is half the maximum and, therefore, half the total, and the average kinetic energy is likewise half the total energy.

الاكثر قراءة في الميكانيك

الاكثر قراءة في الميكانيك

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)