Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Markedness

المؤلف:

Mehmet Yavas̡

المصدر:

Applied English Phonology

الجزء والصفحة:

P207-C8

2025-03-20

1392

Markedness

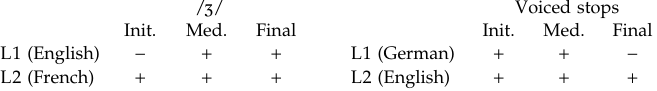

The different types of phonemic mismatches discussed above may be helpful in sorting out different degrees of difficulty that learners experience in the acquisition of L2 phonology. They are, however, far from depicting the whole picture. The reason for this is the varying nature of structural elements with respect to their markedness. Markedness of a structure is derived from its common occurrence in languages. Simply stated, a structure (constraint) A is more marked than another structure B if cross-linguistically the presence of A in a language implies the presence of B, but not vice versa (Eckman 1977, 1985; Eckman and Iverson 1994). Accordingly, two structures A and B, of which the first is more marked than the second, will present different degrees of difficulty for L2 learners. The classic example frequently discussed consists of the following two identically characterized situations provided by the mismatches of (a) German–English and (b) English–French, with respect to voiced–voiceless contrast in obstruents. The voiced and voiceless stop series /b, d, g/ and /p, t, k/ are part of the inventory of both English and German. While both languages contrast the voiced and voiceless series in word-initial and word-medial positions, the final position contrast is available only in English (e.g. back– bag); German neutralizes the contrast in favor of the voiceless member, and does not allow the voiced member in this position. The mismatch created in this position can easily predict the difficulty that German speakers have in learning English final voiced stops, with commonly observed substitutions such as cab [kæb] → [kæp], bed [bεd] → [bεt], and so on.

The second situation that can be described identically is a contrast existing in all word positions in L2 but neutralized in one of the word positions in L1. For this, we will consider the /ʃ/ vs. /Ʒ/ contrast in English and in French. While both languages contrast the two sounds in medial and final positions, the initial contrast is available only in French. The prediction from this discrepancy is that speakers of English learning French will have difficulties for the above-mentioned contrast in word-initial position similar to that of German speakers’ difficulties for the final voiced stops of English.

Both cases reveal descriptively identical situations in that L2 has no restrictions of occurrence of the target in any word positions, while L1 has a positional restriction (i.e. English does not have /Ʒ/ in initial position, and German does not have voiced stops in final position). Professionals who have observed these two identically describable mismatches would quickly point out that the difficulties experienced in these two situations are very different, and acquisition of the English final voiced stops by German speakers is a much greater challenge than acquisition of French initial /Ʒ/ by speakers of English. Although both situations described deal with the voicing contrast in obstruents (/ʃ/ – /Ʒ/ in fricatives, /p, t, k/ – /b, d, g/ in stops), acquiring the voicing contrast in final position is a more marked phenomenon than doing the same in initial position. Cross-linguistically, voicing contrast in final position implies the contrast in initial position, but the reverse is not known to be true. Accordingly, the difficulty of acquiring the voiced stops is a result of the more marked nature of voicing contrast in final position. Thus, while simple contrastive analysis can make predictions on the basis of the mismatches between L1 and L2, it cannot go beyond that. It is only by referring to the relative markedness of the structures that we can account for the variable performance of learners for seemingly identical situations.

Digging further into the markedness relations, we can discover other factors that are relevant for remediation. For example, it has been observed that learners have greater difficulty in acquiring the voicing contrast with velars (i.e. /k/ vs. /g/) than with alveolars (i.e. /t/ vs. /d/); bilabials are the least difficult. That is, the tendency to neutralize the contrast by devoicing is greater as the place of articulation moves further back. There is an aerodynamic explanation for such differences based on the place of articulation. The larger the supraglottal area for a stop, the better it can accommodate glottal flow for some time before oral pressure exceeds subglottal pressure and stops the vocal cord vibration. Since the cavity size gets increasingly smaller as we move from bilabial /b/ to alveolar /d/ and then to velar /g/, the velar has the least chance of maintaining the glottal flow and, thus, is more quickly devoiced.

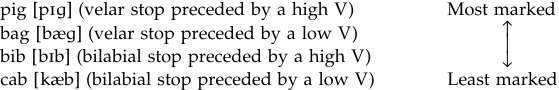

It has also been suggested (Yavas 1997) that the height of the vowel preceding the final voiced stop may be an important factor for final devoicing. Specifically, increasing the height (i.e. decreasing the sonority index) of the vowel creates a more favorable environment for the devoicing of the final voiced stop target. The reason offered for this is that high vowels (i.e. lower sonority vowels), by raising the tongue and creating more constriction than other vowels, cause higher supraglottal pressure and are more prone to devoicing (Jaeger 1978). This vulnerability to devoicing seems to be carried over to the following final voiced stop. Thus, putting everything together, we might find a variable success rate, for example, for the following different combinations with different degrees of markedness:

Another example to show the insufficiency of simple contrastive analysis and the necessity of the markedness considerations comes from the coda consonants. While CV is a universally unmarked syllable structure in languages (i.e. no known language lacks CV syllables), any addition to it adds a degree of markedness. A CVC syllable, while not a highly marked structure, may be completely absent from a language, or alternatively may have some restrictions regarding what class of consonants can occupy the coda position. For example, in a language such as Japanese, only /n/ is permitted as a single coda. A simple contrastive analysis will predict that any single coda other than a nasal (i.e. obstruent, liquid) in an English target word would be problematic for a Japanese speaker. While this prediction is accurate in a general sense, the degree of difficulty experienced by learners in different classes of sounds is significantly different; for example, obstruent codas present much greater difficulties than liquid codas. This situation, while inexplicable via contrastive analysis, is actually quite expected if we take into account the relative markedness of certain groups of sounds in coda position. Universally, obstruents are more marked (i.e. less expected) as singleton codas. In a language with CVC syllables, the coda position is most usually occupied by sonorants. There are two patterns that are observed in languages that allow CVC syllables: (a) obstruent and sonorant codas (e.g. English), and (b) only sonorant codas (e.g. Japanese). There is no language that has obstruent codas but lacks sonorant codas; this indicates that sonorants are more natural (unmarked) as codas than are obstruents. Actual examples from L2 learning situations support this view strongly. For example, for speakers of languages in which some obstruents and sonorants are permitted as codas, such as Korean, Japanese, Cantonese (Eckman and Iverson 1994), and Portuguese (Baptista and DaSilva Filho 1997), the difficulty encountered in learning single codas of English reflects the same hierarchy of difficulty, i.e. obstruents are more difficult than sonorants.

Patterns of acquisition of English liquids are also quite revealing with respect to markedness conditions. English makes a contrast between /l/ and /ɹ̣/ in all word positions. A language such as Mandarin restricts its contrasts between the liquids to the onset position; there are no syllabic liquids, and only /r/ is found in coda position. A simple contrastive analysis will predict that Mandarin speakers will be successful in onset position, and the liquid targets of English in other positions will be difficult. Paolillo (1995) examined the rendition of English liquids in five different environments: word-initial (e.g. rain, leaf), postconsonantal (e.g. play, free), intervocalic (e.g. around, polar), syllabic nucleus (e.g. razor, apple), and postvocalic (e.g. fall, cart), and found that there was a hierarchy of environments for successful rendition of the contrasts between the target English liquids. In descending order of favorable environments, it was word-initial, syllabic, intervocalic, postconsonantal, and postvocalic. If learners were not successful in one environment, it implied that they were not successful in the environment(s) that came after in the order. For example, if a learner had a problem in the intervocalic environment, she or he would have a problem in the postconsonantal and postvocalic environments. The explanation comes from the relative markedness of liquids in different environments, which relates to relative acoustic salience in each of these environments. Specifically, the relative salience is higher in initial or syllabic position than in other transitory positions or in clusters. This example shows that learners’ difficulties cannot be explained by a simple contrastive analysis mismatch between L1 and L2, and the relative markedness of the targets in different environments should be considered.

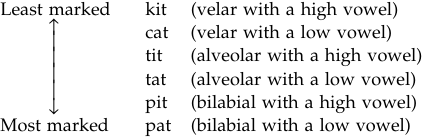

For another example of the invaluable insights we can gain from marked ness, we turn our attention to the aspirated vs. unaspirated stop mismatches between English and several other languages, which are a significant source of trouble. While English has aspirated stops in syllable-initial position, stops in languages such as Spanish, Portuguese, and so on are not aspirated. Thus, it is commonplace that speakers coming from these languages experience difficulties in their attempts to learn English; they replace the aspirated target stops [ph, th, kh] with their unaspirated versions [p, t, k]. While a contrastive analysis between L1 and L2 can predict that these mismatches will create difficulties, it cannot say anything about the varying degrees of difficulty among different targets. Several studies (Laeufer 1996; Port and Rotunno 1978; Thurnburg and Ryalls 1998; Major 1987; Yavas 1996, 2002) found that learners experience less difficulty in acquiring the aspirated stops as we go from bilabial to alveolar and to velar. In other words, we are dealing with the relative markedness among [ph, th, kh], the first being the most marked and the last being the least marked. The reason for the varying degrees of ease or difficulty (markedness) is related to the degree of abruptness of the pressure drop upon the release of a stop. The more sudden (abrupt) the pressure drop is, the sooner the voicing of the next segment (vowel or liquid) starts. In the case of different places of articulation, differences in the mobility between the articulators involved in occlusion are responsible for the different degrees of abruptness of the pressure drop. The tongue dorsum separates more slowly (i.e. less abruptly from the velum for the velar /k/ than the tongue tip from the alveolar ridge /t/, or the lips /p/). The slower, thus longer, release delays the proper pressure differential to begin voicing for the following segment, hence the longer lag (aspiration) for velars than for alveolars and labials.

It has also been suggested (Weismer 1979; Flege 1991; Klatt 1975; Yavas 2002) that the sonority of the following segment may influence the degree of aspiration of the stop. An initial stop seems to have a longer lag before a segment that has a narrower opening (i.e. lower sonority index), such as a high vowel, than before another that has a more open articulation (i.e. high sonority index), such as a low vowel. The reason for this is that lower-sonority items (e.g. high vowels) have a more obstructed cavity than high-sonority items (e.g. low vowels). Since the high tongue position that is assumed during the stop closure in anticipation of a subsequent high vowel would result in a less abrupt pressure drop, a stop produced as such will have a longer lag than before a low vowel.

Putting all these together, we can show the relative markedness of the following:

Our final example with respect to markedness comes from a sequential relationship and looks at English double onsets in which the first member is /s/. The possibilities can be described as (a) /s/ + stop (e.g. speak, stop, skip), (b) /s/ + nasal (e.g. small, snail), (c) /s/ + lateral (e.g. sleep), and (d) /s/ + glide (e.g. swim). Several languages that allow double onsets do not have the above combinations, and Spanish is one such language. Thus, it is expected that Spanish speakers will have difficulties with the initial sC (where C = consonant) targets in learning English and, indeed, they do. What is interesting, however, is that the difficulties experienced by the learners are not the same with respect to the different combinations of s-clusters (a), (b), (c), and (d) listed above. A decreasing degree of difficulty has been observed for (a) – (d) in the learning of English: /s/ + stop being the hardest, and /s + w/ being the least difficult.

While a contrastive analysis between the two languages could predict that English initial sC clusters will be difficult for Spanish speakers (because Spanish does not have them), it will have no means of going beyond that to account for the different degrees of difficulty observed. Here, again, the explanation will come from the relative markedness of the targets. The relative naturalness of clusters is closely linked to the principle of sonority sequencing, which dictates that the sonority values should rise as we move from the margin of the syllable to the peak (nucleus). Among the targets in question, one of them, (a) /s/ + stop, violates this principle, because the first member of the onset cluster, /s/, a voiceless fricative, has a higher sonority value, 3, than the second member, /p, t, k/, which has 1. Thus, as we move from C1 to C2, a ‘fall’, rather than the expected ‘rise’, in sonority takes place. Since this is a highly unexpected (marked) combination in universal terms, it is not surprising that it proves to be a very difficult target to acquire. The remaining targets, (b) /s/ + nasal, (c) /s/ + lateral, and (d) /s + w/, all satisfy the sonority sequencing generalization, because there is a ‘rise’ in sonority as we move from C1 to C2 (/s/ + nasal: 3 to 5; /s/ + lateral: 3 to 6; /s + w/: 3 to 8). As we noted earlier, there was a decreasing degree of difficulty among these three targets, and this also is explainable with reference to their relative naturalness. The fact that laterals are higher in sonority than nasals, and glides are higher than laterals, results in different degrees of sharpness in the sonority jumps between C1 and C2, and this seems to be responsible for the greater ease of /sw/ (sonority difference of 5) than /sl/ (sonority difference of 3). Similarly, /sl/ has a bigger difference than /s/ + nasal (sonority difference of 2) and thus, expectedly, provides less difficulty.

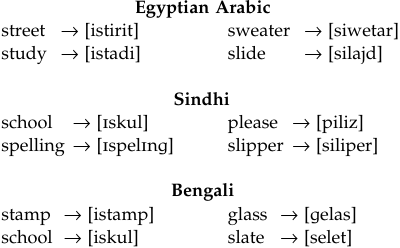

It is also worth mentioning that speakers coming from languages that do not permit any onset clusters reveal different modification patterns with respect to different types of English clusters in contact situations. Error patterns of speakers of Egyptian Arabic, Sindhi, and Bengali (Broselow 1993) show that sonority sequencing-violating /s/ + stop clusters are modified with a prothetic vowel, while the ones that do not violate the sonority sequencing receive an epenthetic vowel, which results in a speedier, native-like pattern:

While, for reasons of space, we will not go on to other examples that demonstrate the importance of markedness, similar examples can easily be multiplied for many other phonological structures. The important message that comes out of all these is to alert remediators about the indispensable nature of such information. The more one can see the highly structured nature of events, the better remediator one can become.

الاكثر قراءة في Phonology

الاكثر قراءة في Phonology

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)