Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Binary features

المؤلف:

THOMAS G. BEVER and PETER S. ROSENBAUM

المصدر:

Semantics AN INTERDISCIPLINARY READER IN PHILOSOPHY, LINGUISTICS AND PSYCHOLOGY

الجزء والصفحة:

586-33

2024-08-26

1300

Binary features

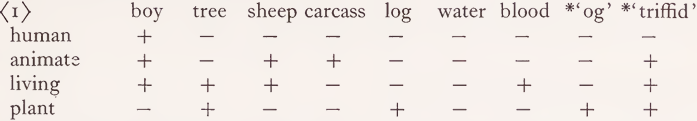

Consider first the use of features in semantic description. It is not radical to propose that words are categorized in terms of general classes. Nor is it novel to consider the fact that these classes bear particular relations to each other. Consider, for example, the English words in the matrix presented in (1):

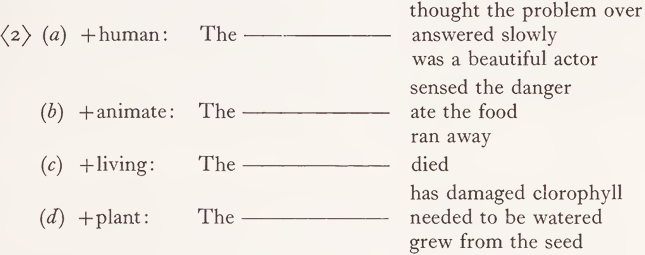

In this chart words are represented in terms of particular binary dimensions. In each case the particular semantic dimension, or ‘semantic feature’, is the marking which specifies particular aspects of the semantic patterning of the lexical item. In (2) the positive value for each feature is associated with some sample sentence frames which indicate the kind of systematic restrictions each feature imposes. Thus in (2a) any noun marked ‘+ human’ can, among other things, appear in the sentence ‘The noun thought the problem over’, but any noun marked ‘ — animate’ cannot appear in the frame ‘the noun sensed the danger’; any noun marked ‘ + plant’ can appear in the frame ‘the noun has damaged clorophyll’. The privileges of occurrence in these kinds of frames of the different nouns in the figure are indicated by the placement of the ‘ + ’ and ‘ — ’ markings on the separate features.

It has rarely been questioned that such classifications play a role in natural language.2 But the problem has been to decide which of the many possible aspects of classification are to be treated as systematically pertinent to a semantic theory. We cannot claim to have discovered all and only the semantic features of natural language. However, it is absolutely necessary to assume that there is some universal set from which particular languages draw their individual stock.

Furthermore, if the semantic analysis of natural language is to achieve explanatory adequacy, there must be a principled and precise manner of deciding among competing semantic analyses. In this way the semantic analysis which is ultimately chosen can be said to be the result of a formal device, and not due to the luck of a formal linguist. If the particular analysis is chosen on the basis of precise, formal criteria then the reality of the predictions made by the device constitutes a confirmation of the general linguistic theory itself.

Lexical analysis of single words includes a specification in terms of a set of semantic features. We propose, furthermore, that the most highly valued semantic analysis which meets these constraints be the one which utilizes the smallest number of symbols in a particular form of semantic analysis. For a given natural language this will direct the choice of which features are drawn from the universal set as well as the assignment of predictable features in the lexicon itself.

1 This work was supported by the MITRE corporation, Bedford, Mass., Harvard Society of Fellows, NDEA, A.F. 19(68)-5705 and Grant # SD-187,1 Rockefeller University and IBM. A preliminary version of this paper was originally written as part of a series of investigations at MITRE corporation, summer 1963, and delivered to the Linguistic Society of America, December 1964. We are particularly grateful to Dr D. Walker for his support of this research and to P. Carey and G. A. Miller for advice on this manuscript.

The paper is reprinted from R. A. Jacobs and P. S. Rosenbaum (eds.), Readings in English Transformational Grammar, Blaisdell, 1970.

2 Modern discussions of such features and their integration within grammatical theory can be found in Katz and Fodor, 1963; Chomsky, 1965; Miller, 1967. In this article we will assume that the reader has a basic familiarity with the role of semantic analysis in current transformational linguistic theory.

الاكثر قراءة في Semantics

الاكثر قراءة في Semantics

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)