Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Clauses

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Direct and Indirect speech

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Situation types

المؤلف:

Patrick Griffiths

المصدر:

An Introduction to English Semantics And Pragmatics

الجزء والصفحة:

66-4

14-2-2022

2967

Situation types

The historical starting point is an article by Zeno Vendler (1967) called ‘Verbs and times’. Much of his discussion concerned verb phrases, rather than verbs in isolation. He classified verb phrases into four kinds, differing according to how the denoted states or actions are distributed in time: almost instantaneous switches between states (as with notice a mistake), simple existence of a state (for example, hate hypocrisy), ongoing actions (like ring handbells) and goal-directed actions that culminate (cook dinner, for example). It is worth extending the domain from verb phrases to clauses, because the subject of the clause can be important too: for instance, while Jo cooked dinner describes a culminating activity, if First one home cooked dinner was the rule for a household, then the latter sentence denotes a state rather than an activity.

Vendler’s (1967) paper is a classic, the basis for a substantial field of research on the interface between syntax and semantics. Vendler’s labels and much of his framework continue to be used, but no attempt is made here to distinguish the original version from subsequent changes. Instead, a sketch will be given of the semantic side of this work as it was around the turn of the century. (My account owes quite a lot to Levin and Rappaport 1998, Tenny and Pustejovsky 2000, and Huddleston and Pullum 2002).

The four sentences in (4.7) illustrate Vendler’s four kinds of situation. His labels are given in parentheses. They are technical terms that are going to be explained here. Though achievement and accomplishment have positive connotations in ordinary usage, they are evaluatively neutral when we are talking about situation types.

Get and have are among the most frequently used English verbs (Leech et al. 2001: 282) and both have several meanings, but for present purposes it is essential to keep with a single meaning for each of the sentences in (4.7). Think of (4.7a) as a description of a one-off sports accident and of (4.7d) as expressing the person’s recovery from the accident. The main verb in both is get, but different senses of get are in play. The accident (4.7a) is a sudden transition from ankle being okay to ankle being sprained. In a transition of this kind – an achievement – there is not usually enough time to avoid the outcome by stopping partway through. This shows in the unacceptability of *She stopped getting her ankle sprained. It is different with the accomplishment meaning of get (seen in 4.7d): there is nothing linguistically strange about She stopped getting better. The culmination is a state of good health, but getting better also encodes a healing process that leads up to it, and English allows us to talk of stopping during that process, before the end result has been reached.

A subsidiary point needs to be made about the phrase get better in (4.7d), which, in the way I asked you to understand it, has the idiomatic meaning ‘recover one’s health’. Ill and “health-recovery better” form a pair of complementaries. We can reasonably wonder whether a person who was ill is completely better, and in ordinary conversation I have heard the argument made that “If you are not completely better, then you are still ill”. No matter how gradual or constant the rate at which someone recovers, the sentence She got better encodes it as if a sharp boundary into good health is eventually crossed. With a gradable adjective such as bigger, the adverb completely yields semantically dubious sentences: *Tokyo is completely bigger than London. (If She got better is taken as a description of improvement in someone’s volleyball playing, then better is the comparative form of a gradable adjective and, just like bigger, rejects modification with completely.)

Another indication that English treats achievements, like (4.7a), as if they were instantaneous, but accomplishments, like (4.7d), as having a pre-culmination phase spread out in time is the contrast between *She was getting her ankle sprained – no good on the one-off accident reading – and the normality of She was getting better. This is because progressive aspect marking (BE + Verb-ing) highlights the durative phase of an event and ignores its termination. Achievements are encoded as not having duration, so progressive aspect is in-applicable to (4.7a), while the lead-in phase of an accomplishment has duration, allowing progressive marking on (4.7d).

Progressive aspect marks not only duration – extendedness in time (and hence its unacceptability with the abrupt changes called achievements) – it also signals dynamism. Progressive marking does not go well with clauses describing situations where nothing happens, where there is no dynamism. State sentences such as (4.7b) do not readily accept progressive marking: *She was having a sprained ankle. On the other hand, the progressive is freely applicable to the activity use of have in (4.7c): She was having physiotherapy. (Going back to (4.7b) and the progressive: consider the possibility of a speaker saying in all seriousness: She was having a sprained ankle. In real conversations one does not usually say “That’s an asteriskable sentence. Please try something different.” Instead, an interpretation could be made along the following lines: progressive aspect indicates a dynamic performance; so what is being described cannot be the state that we expect have a sprained ankle to denote, it must have been an activity; so perhaps the person with the sprained ankle was making a big show of her suffering.)

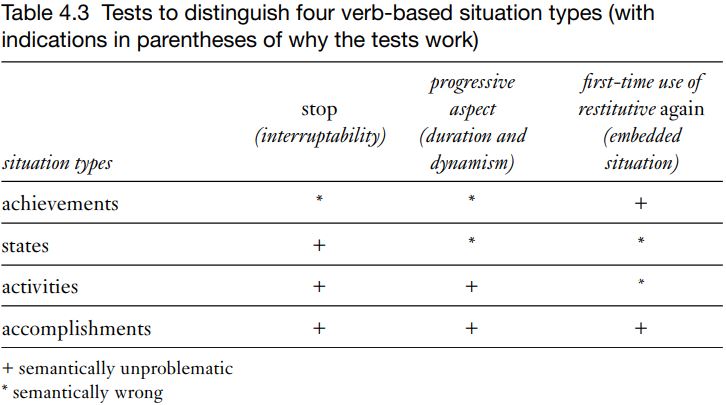

Stop was one of the tests mentioned for distinguishing achievements (4.7a) from accomplishments (4.7d). Both states (4.7b) and activities (4.7c) can be stopped: She stopped having a sprained ankle; She stopped having physiotherapy. The first of these might not be the best way to say that the person in question no longer had a sprained ankle, but I think it is good enough for a plus sign to go under stop in the states row of Table 4.3. Add a query mark if you wish; states will still be distinguished from the other situation types.

Examination of the first two columns of asterisks and pluses in Table 4.3 shows that these two tests alone are not sufficient to distinguish activities from accomplishments: both are double-plus. The possibility of first-time use of restitutive again, makes the distinction. An activity, such as (4.7c), modified by again can only be understood as the activity happening for a second or subsequent time: She had physiotherapy again. (It worked for her before; so let’s hope it does this time.) But if an accomplishment, such as (4.7d), results in restitution of a state that the subject was in before, first-time use of again is possible: She got better again. (I’m so glad, because she had never had health problems before.) This suggests that, similarly to causatives, accomplishments have an “understood” embedded situation: ‘she be in good health’ for (4.7d). There is no named causer in (4.7d), but as with the causatives, this embedded situation is entailed: She got better ⇒She was better. The time for the tense of the embedded proposition comes from got, the overt verb of (4.7d); so She was better to the right of the entailment arrow is taken as becoming true at the time that She got better became true.

Table 4.3 shows states and activities asterisked in the restitutive-again column. This does not mean that the wording is ruled out. It is simply that She had a sprained ankle again and She had physiotherapy again are false (a serious semantic problem) if we are talking about the first time she had a sprained ankle or had physiotherapy. To understand why achievements have a plus under restitutive again, imagine a foetus developing, from the beginning, with a sprained ankle and therefore being born with one. Imagine that physiotherapy sorts out the problem and the infant stops having a sprained ankle,5 but learning to walk about a year later there is an accident and she sprains her ankle. Even if this is the child’s first accident of any kind, it can be reported using restitutive again on the achievement sentence (4.7a): She got her ankle sprained again.

الاكثر قراءة في Semantics

الاكثر قراءة في Semantics

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)