Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension|

Read More

Date: 2024-04-17

Date: 2024-03-16

Date: 2024-05-22

|

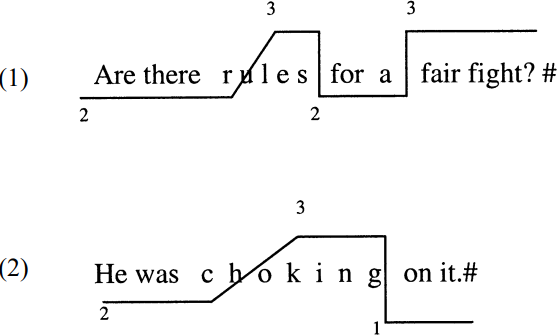

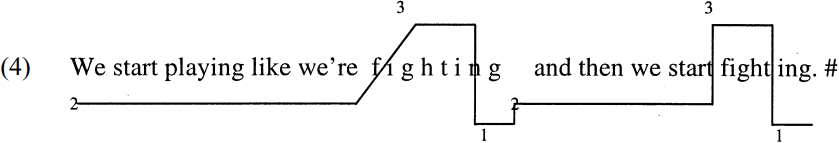

Five major patterns occur variably in ChcE (Penfield 1984). First, there is the ChcE rising glide, which “can occur at almost any point in a contour” (Penfield and Ornstein 1985: 48), as in rules and choking in the following sentences:

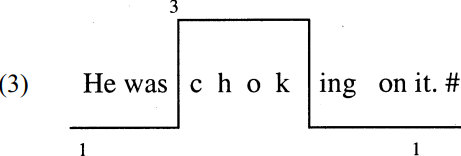

The glide is accompanied by a lengthening of the affected syllables. Penfield and Ornstein indicate the distinctiveness of ChcE is that unstressed portions of multisyllabic words, e.g. -ing, are maintained at the higher pitch level (1985: 49). The equivalent pattern in AmE would be:

Penfield (1984) states that the rising glide is associated with emphasis on the specific word, and not the contrastive stress that would be the case in AmE. Penfield and Ornstein (1985) offer (4) as an example of the same word appearing twice in a sentence, once with the rising glide (marking emphasis), and the more general step-down pitch contour, which does not have this added meaning:

A second aspect of this ChcE pattern is that, if the glide occurs on the last stressed syllable of the utterance, the pitch of glide can be maintained, whether or not the intent is emphatic or not. Neutral declarative utterances do not necessarily end with a falling step contour, as is the typical AmE pattern:

Example (5) is a contrastive use of the glide, spoken by a Chicana who narrated her conversation with her physician where she makes a “countercomment” (1984) stating that she did not want to be sedated when she delivered the baby. Penfield indicates that a syllable-final rising glide in AmE dialects tends to express doubt, surprise or questions. In ChcE, it does not necessarily convey such notions.

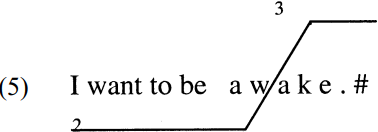

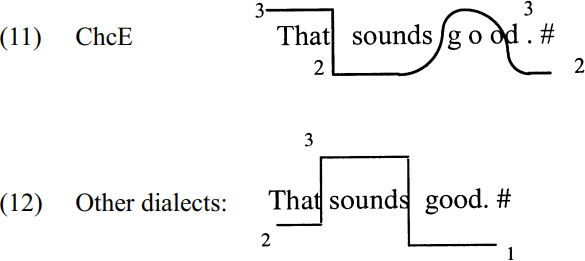

In a related final contour distinction, ChcE non-emphatic declarative utterances can end on middle pitch, rather than falling to low pitch in a step. This is the pattern that might briefly confuse speakers of other English dialects, who expect a more pronounced falling contour to signal the end of an utterance:

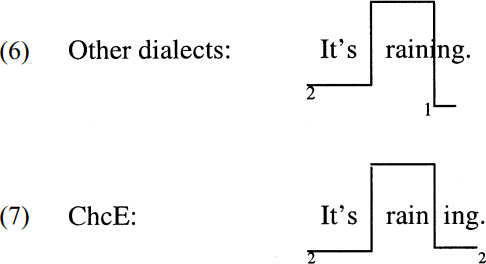

The third ChcE pattern concerns initial pitch position. A ChcE utterance can begin on a high pitch, which is mistakenly interpreted by speakers of other dialects as focus. This high pitch does not necessarily mark focus. In some cases, it apparently marks solidarity. At other times, its meaning is harder to pin down:

This ChcE initial high pitch does not function to signal emphasis. Penfield and Ornstein suggest that it is this prosodic contour that gives AmE speakers the “folk conception that Chicanos are highly emotional or excited, since the use of a high pitch at pre-contour level—especially if it spanned over more than a word—would certainly convey such a meaning in Standard English” (1985: 50).

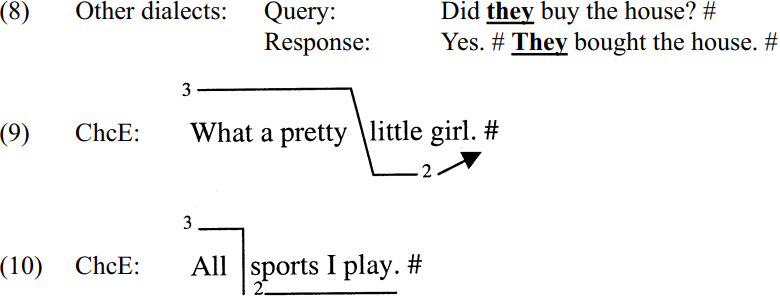

Four, ChcE has a distinctive gliding-final contour, that is, at the end of utterances/sentences. Compare the USEng step-like fall that marks its sentence-final contour. This ChcE terminal contour most often signals emphasis or affect. In contrast to the ChcE gliding contour, the Euro-American tune typically expresses emphasis with abrupt block-like steps of pitch:

This is the stereotypic pattern that Euro-American actors use when playing Mexican bandits or peasants in Hollywood Westerns. It is also the intonation of the Warner Bros. cartoon character, Speedy Gonzales. This is not a subtle caricature of a Mexican, no matter what its original intent. The mouse is outfitted with Mexican sombrero, and Mexican peasant clothing dating from no later than the 1920s, in contrast to the cartoon’s origin in the 1950s. It offers a White American’s derisive depiction of Spanish-accented English. It should be noted that ChcE speakers who use the rise/fall gliding final contour will also use the local matrix Euro-American English step-like final contour.

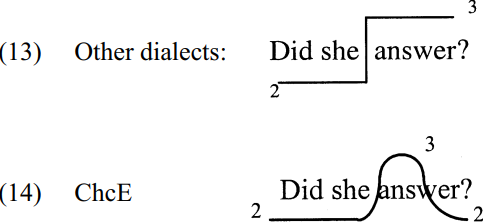

Five, rather than using the AmE yes/no question contour, which again is a block-like step that ends on a low pitch, ChcE speakers variably employ another gliding contour that does not end in a final low pitch:

Fought (2003: 75–76) continues that these terminal contours are distinct from the so-called U.S. American cross-dialect “uptalk” contour that is used in non-emphatic declaratives, in spite of the fact that both the ChcE contour and the uptalk contour do not end in a falling pitch. Santa Ana can confirm that in his current contact with Los Angeles ChcE speakers he can distinguish both declarative contours.

Intonational contours, arguably the most changeable and ephemeral elements of speech, are very readily reified. At this point it is useful to recall that these speech utterance patterns are rendered vexingly complex by individual language histories, speech event features such as topic, setting, and, among many other social factors, interlocutor. Add to this the complexity inherent in cultural features such as habituated verbal practice and, in contrast, mapping patterns of responses to novel interactional situations. Moreover, it is important to consider the open flexibility that individuals have in the moment of their speaking turn. In studies of naturally occurring prosody, we must add the issue of the observer’s paradox, and the impossibility to replicate speech events—however closely one reproduces the setting. The traditional scientific response to such research circumstances, namely large-scale projects designed to wash out variation, are entirely inappropriate in these circumstances. This makes the goal of characterizing ChcE intonation in its dynamic contact setting a first-order methodological challenge.

Fought (2002: 72–76) provides a fascinating angle on some ChcE intonation patterns, drawing on Joseph Matluck’s (1952) description of the Spanish language circumflex pattern of the Mexican altiplano (the high plateau formed between the eastern and western Sierra Madre mountain chains). To find the origin of the circumflex pattern, Matluck points to another substrate language: “The distinctive musical line in the unfolding of the phonetic group is probably the most striking trace that the Nahuatl language has left in the Spanish of the Valley [of Mexico City] and the plateau: a kind of song with its curious final cadence, very similar to the melodic movement of Nahuatl itself”. Fought continues to translate Matluck: “From the antepenultimate syllable to the penult there is a rise of about three semitones, and from there to the final a fall of six semitones more or less. Both the penult and the final syllables are lengthened” (Fought 2002: 74). Matluck also describes a working-class feature that can be found in ChcE, namely lengthening of stressed vowels at the start and the end of a phrase:

Accented syllables in vernacular speech in the Valley tend to be much longer than those of the educated class and in Castilian generally; on the other hand, unaccented syllables are shortened. The overall impression is of syllabic lengthening at the beginning and especially at the end of the sentence, and of shortening in the middle. For example: Don’t be bad > Doont be baaad; I have to do it soon > III have to do it sooon (quoted in Fought 2002: 75).

Fought states that not only is this pattern readily observed in the English ELLs, it is also heard in the speech of ChcE native speakers. Once again, the substrate Mexican Spanish influence has not disappeared in ChcE, it has been transformed into another feature of in-group solidarity.

|

|

|

|

التوتر والسرطان.. علماء يحذرون من "صلة خطيرة"

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

مرآة السيارة: مدى دقة عكسها للصورة الصحيحة

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

نحو شراكة وطنية متكاملة.. الأمين العام للعتبة الحسينية يبحث مع وكيل وزارة الخارجية آفاق التعاون المؤسسي

|

|

|