Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

More elaborate word forms: multiple affixation

المؤلف:

Andrew Carstairs-McCarthy

المصدر:

An Introduction To English Morphology

الجزء والصفحة:

72-7

2024-02-03

1737

More elaborate word forms: multiple affixation

Many derived words contain more than one affix. Examples are unhelpfulness and helplessness. Imagine now that the structure of these words is entirely ‘flat’: that is, that they each consist of merely a string of affixes plus a root, no portions of the string being grouped together as a sub-string or smaller constituent within the word. An unfortunate consequence of that analysis is that it would complicate considerably what needs to be said about the behavior of the suffixes -ful and -less. These were straightforwardly treated as suffixes that attach to nouns to form adjectives. However, if the nouns unhelpfulness and helplessness are flat-structured, we must also allow -ful and -less to appear internally in a string that constitutes a noun – but not just anywhere in such a string, because (for example) the imaginary nouns *sadlessness and *meanlessingness, though they contain -less, are nevertheless not words, and (one feels) could never be words.

The flat-structure approach misses a crucial observation. Unhelpfulness contains the suffix -ful only by virtue of the fact that it contains (in some sense) the adjective helpful. Likewise, helplessness contains -less by virtue of the fact that it contains helpless. Once that is recognized, the apparent need to make special provision for -ful and -less when they appear inside complex words, rather than as their rightmost element, disappears. In fact, both these words can be seen as built up from the root help by successive processes of affixation (with N, V and A standing for noun, verb and adjective respectively):

(1) help N + -ful → helpfulA

un- + helpful → unhelpfulA

unhelpful + -ness → unhelpfulness N

(2) help N + -less → helplessA

helpless + -ness → helplessness N

Another way of representing this information is in terms of a branching tree diagram, as in (3) and (4), which also represent the fact that the noun help is formed by conversion from the verb:

(The term ‘tree diagram’ is odd, because the ‘branches’ point downwards, more like roots than branches! However, this topsy-turvy usage has become well established in linguistic discussions.) The points in a tree diagram from which branches sprout are called nodes. The nodes in (3) and (4) are all labelled, to indicate the wordclass of the string (that is, of the part of the whole word) that is dominated by the node in question. For example, the second-to-top node in (3) is labelled ‘A’ to indicate that the string unhelpful that it dominates is an adjective, while the topmost node is labelled ‘N’ because the whole word is a noun. The information about structure contained in tree diagrams such as (3) and (4) can also be conveyed in a labelled bracketing, where one pair of brackets corresponds to each node in the tree: [[un-[[helpV]N-ful]A]A-ness]N, [[[helpV]N -less]A-ness]N.

One thing stands out about all the nodes in (3) and (4): each has no more than two branches sprouting downwards from it. This reflects the fact that, in English, derivational processes operate by adding no more than one affix to a base – unlike languages where material may be added simultaneously at both ends, constituting what is sometimes called a circumfix. English possesses no uncontroversial examples of circumfixes, and branching within word-structure tree diagrams is never more than binary (i.e. with two branches). (The only plausible candidate for a circumfix in English is the en- …-en combination that forms enliven and embolden from live and bold; but en- and -en each appears on its own too, e.g. in enfeeble and redden, so an alternative analysis as a combination of a prefix and a suffix seems preferable.) The single branch connecting N to V above help in (3) and (4) reflects the fact that the noun help is derived from the verb help by conversion, with no affix.

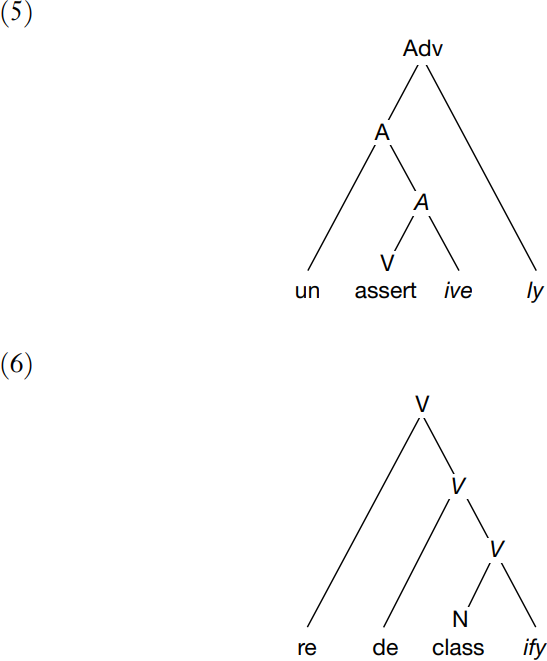

At (5) and (6) are two more word tree diagrams, incorporating an adverbial (Adv) node and also illustrating both affixal and non-affixal heads, each italicized element being the head of the constituent dominated by the node immediately above it:

Some complex words contain elements about which one may reasonably argue whether they are complex or not. For example, the word reflection is clearly divisible into a base reflect and a suffix -ion; but does reflect itself consist of one morpheme or two? If we put it on one side, then any complex word form consisting of a free root and affixes turns out to be readily analyzable in the simple fashion illustrated here, with binary branching and with either the affix or the base as the head. (I say ‘free root’ rather than ‘root’ only because some bound roots are hard to assign to a wordclass: for example, matern- in maternal and maternity.)

Another salient point in all of (3)–(6) is that more than one node in a tree diagram may carry the same wordclass label (N, V, A). At first sight, this may not seem particularly remarkable. However, it has considerable implications for the size of the class of all possible words in English. Linguists are fond of pointing out that there is no such thing as the longest sentence of English (or of any language), because any candidate for longest-sentence status can be lengthened by embedding it in a context such as Sharon says that ___ . One cannot so easily demonstrate that there is no such thing as the longest word in English; but it is not necessary to do so in order to demonstrate the versatility and vigour of English word-formation processes. Given that we can find nouns inside nouns, verbs inside verbs, and so on, it is hardly surprising that the vocabulary of English, or of any individual speaker, is not a closed, finite list.

الاكثر قراءة في Morphology

الاكثر قراءة في Morphology

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)