Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Verbal derivation and the separation hypothesis

المؤلف:

Ingo Plag

المصدر:

Morphological Productivity

الجزء والصفحة:

P237-C8

2025-02-15

1377

Verbal derivation and the separation hypothesis

I have put forward a sign-based theory of verbal derivation where each class of derivatives has its own semantic and phonological properties. Separationist theories proposed completely different accounts. I will argue in detail that a sign-based approach is preferable.

Gussmann (1987) claims that there is a derivational rule ("the uniform semanto-syntactic formula whereby adjectives become verbalized", Gussmann 1987:82), with the meaning 'make (more) X', where X stands for the adjective. The pertinent spell-out operations include the affixes eN-, be-, -en, -ify, -ize, -ate and ∅. However, such an account can neither account for the differences in meaning between the different affixes, nor can it explain the polysemy of individual affixes.

To save the separationist approach (also with regard to denominal verbal derivation) one could perhaps postulate a number of different derivational rules such as stative, inchoative, causative, ornative (cf. Szymanek 1988:180-181), mapped onto the morphological spell-out rules in complex ways. This solution leads, however, to a proliferation of derivational rules for which there is no independent evidence. Thus, I fail to see how the derivational rules can be motivated, if not through their manifestation in speech. Szymanek (1988) proposes that the derivational categories are ultimately grounded in cognitive concepts. While this may well be the case, a direct connection between the cognitive categories and the derivational categories can be excluded in view of the abundance of differences between the derivational categories across languages. The derivational categories can therefore only be motivated by making reference to the individual signs in the specific language.1 The fact that semantic categories like causation play a role in so many languages speaks for the universality of the concept, but not necessarily for the separation hypothesis. It is thus unclear to me how many derivational rules one would have to propose in order to account for the many different interpretations of our derived verbs, and how the selection of these rules can be independently justified. In sum, Gussmann's separationist account of verbal derivation should be rejected.

In a more recent treatment of verbal derivation, Beard (1995: chapter 8) offers another solution within the separationist framework. He argues that -ize, -ify, -ate, and ∅ are spell-out operations of two different derivations, the transposition of nouns into verbs and the transposition of adjectives into verbs. In his theory, transposition is a lexical derivation without semantic content which only changes the syntactic category of the base. Transposition thus contrasts with so-called functional derivation, which has a semantic effect on the base. Agentive -er as in baker and locative -ery as in bakery are examples of functional derivation.

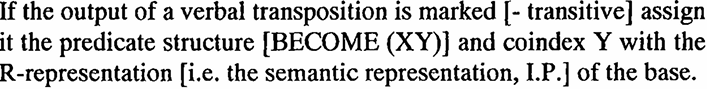

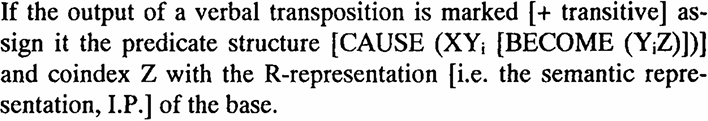

With regard to de-adjectival verbal derivation, the change of category is performed by the neutralization of the adjectival feature [gradable] and the assignment of the feature [+/- transitive]. According to Beard, the causative and inchoative meanings of -ize, -ify and -ate derivatives result from the feature [+/- transitive] via so-called correspondence rules, which are required to interpret this feature in semantics. The correspondence rules are given in (1) and (2) (taken from Beard 1995:181-182):

(1)

(2)

Beard (1995:182) acknowledges the problem that there are zero-derived verbs such as to hammer or to brush that have meanings "even more specific" than predicted by the correspondence rules in (1) or (2). According to his analysis such instrumental meanings can be predicted from the semantic representation of the noun, which specifies its natural function as being an instrument. This functional feature is then selected for the verbal meaning.

Leaving technical details of semantic representation aside, there are a number of problems with the assumption of transposition and with correspondence rules such as (1) and (2). First, as Beard himself admits, the correspondence rules are necessary to interpret the newly assigned feature [+/- transitive]. However, the introduction of correspondence rules makes transposition practically indistinguishable from functional derivation. If semantically empty transposition needs to be enriched by semantic correspondence rules I can see no reason why the semantic effect should not be directly encoded as in functional L-derivation. To complicate matters further, it seems that for the semantic interpretation of instrumental verbs like to hammer, correspondence rules are equally needed. Thus I fail to see by which other mechanism "all features denoting anything other than the natural function may be ignored when the noun is used in a verbal context" (Beard 1995:183). Taking these problems seriously means that the semantics of verbal derivation cannot be reduced to a unitary transposition rule but must involve semantically different derivations, at least for instrumental verbs such as to hammer and causative/inchative verbs such as crystallize. Hence, the crucial assumption of affix synonymy needs to be given up.

Second, the semantics of -ize/-ify and -ate are much more complex than suggested by Beard's correspondence rules. They cannot be explained by semantically empty transposition, even if the transposition is enhanced by the correspondence rules in (1) and (2). Furthermore, the clear semantic differences between -ify and -ize on the one hand, and -ate on the other are unaccounted for. In essence, Beard's approach suffers from a superficial semantic analysis.

Third, under the assumption that zero-derivation and overt suffixation are indeed completely synonymous, it would be surprising if the kinds of more specific meanings (such as instrumental) we frequently observe with converted verbs were confined to this sub-class of derived verbs. But this is exactly what the data show. In a sign-based approach this fact is naturally accounted for, since each class of derivatives has its own semantic and phonological properties. This brings us to the crucial argument for separationist approaches to morphology, the assumed existence of total synonymy of affixes. If affixes are sound-meaning entities they should behave like other sound-meaning entities, i.e. lexemes. With lexemes one can never observe complete synonymy. Hence, sign-based theories predict approximate synonymy of affixes, whereas "LMBM predicts absolute, not approximate synonymy among morphological forms" (Beard, 1995:78, see also Beard 1990b).

It was already pointed out at the beginning of this topic that the assumption of absolute affix synonymy is problematic. Upon closer inspection, putatively synonymous affixes have turned out to show subtle differences in meaning (e.g. Malkiel 1977, Riddle 1985, Doyle 1992). Crucially, this is also the case with regard to verbal derivation in English. Although there is undoubtedly a certain amount of overlap in meaning between the different verb-deriving processes, the detailed semantic analysis has shown that the meaning of -ize and -ify derivatives on the one hand clearly differs from that of -ate derivatives, and the semantics of all kinds of overtly suffixed derived verbs markedly differ from that of converted verbs. In sum, the meanings of the different processes are similar to each other, but still far from being identical. This parallels the situation of lexemes, which in general can only have near synonyms. Only -ify and -ize seem to show the kind of absolute synonymy envisioned by Beard, and we have argued that this is a case of phonologically-conditioned suppletion.

Another argument against Beard's theory is that the verb-deriving affixes quite clearly exhibit polysemy. Hence, Beard's claim that LMH theories tend to produce too many cases of homonymous affixes or involve arbitrary decisions between homonymy and polysemy does not hold in our case. In the sign-based, output-oriented model, the polysemy of the derivatives follows from the same semantic mechanisms that are responsible for the polysemy of non-complex signs, i.e. simplex lexemes. Furthermore, the separationist model cannot explain the polysemy peculiar to the invidual processes. In a separationist model, it is unclear why an individual affix should spell out just the derivational categories it does and not others. For example, why should one verbal suffix spell out different meanings that are related in a specific way? In a sign-based model this follows again from the mechanisms of semantic extension that are characteristic of polysemy in general, i.e. also of the polysemy of simplex lexemes.

Another drawback of a separationist account of derived verbs in English concerns the kinds of restriction that govern the choice of the individual affix. Beard argues that semantic and syntactic restrictions may govern the choice of a particular spell-out operation. For example, null marking in deadjectival nominalizations is restricted by the semantic property of its base word (it must be a color term, Beard 1995:50). If affixation is a purely phonological spell-out process, it is strange that its application depends on non-phonological properties of the base word. Beard is right to assume that indeed many different kinds of properties together may be responsible for the choice of a particular affix. But this is an argument for a sign-based approach, because (only) in a sign-based approach phonological and non-phonological information is not separated.

My last argument against separationist morphology is output-oriented-ness. Beard's theory is essentially a process-oriented model of morphology, making crucial use of traditional rule mechanisms. This study has however demonstrated the empirical and theoretical superiority of output-oriented approaches to morphological processes over rule-based ones. For example, I proposed that in verbal derivation, reference to the syntactic category of the base word is superfluous. This seems not possible in Beard's approach, where for example two transpositional rules are needed to take care of denominal and deverbal affixation. Notably, output-oriented accounts necessarily stress the sign character of complex formations.

To summarize, we have seen that the properties and peculiarities of verbal derivation in English are impossible to explain in a morphological theory that completely separates form and meaning. Exisiting separationist accounts erroneously assume absolute affix synonymy and do not adequately handle the polysemy of individual affixes. The distribution and productivity of the different verb-deriving processes can only be predicted on the basis of the semantic and phonological properties of each class of complex verb, which is impossible to account for under a separationist model in which the mapping of form and meaning is essentially coincidental.

1 Beard (1990b) gleans independent evidence for the postulation of the derivational category 'deadjectival nominalizations' from the fact that across languages, competing processes all entail feminine gender. Impressive though this may be, feminine gender (at least in German) is not only characteristic of deadjectival nominalization but also of deverbal nominalization, a fact that considerably weakens Beard's argument. But what does it tell us that all kinds of nominalizations tend to adopt a certain gender? In my view it tells us that certain derivational processes share certain linguistic properties, no more, no less. Even under a separationist approach such similarities are not entailed by the theory.

الاكثر قراءة في Morphology

الاكثر قراءة في Morphology

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)