Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Ejectives in English

المؤلف:

Richard Ogden

المصدر:

An Introduction to English Phonetics

الجزء والصفحة:

163-10

26-7-2022

1491

Ejectives in English

Ejectives occur in a good number of British English varieties, though remarkably little is known about which ones. Nor is anything much known about the distribution of ejectives. The material on which the observations here are based is collected from a range of sources in Britain, and the following observations seem to be true, but are only indicative. Ejectives occur:

• word finally (and not e.g. before vowels)

• in stressed syllables

• after vowels, nasals and laterals (which are all voiced), but not after voiceless sounds such as [s]

• within utterances (before pauses), as well as at the end of utterances

Ejectives may be a development of glottal reinforcement. In glottal reinforcement, a glottal constriction is made before an oral one; once the oral constriction is made, the glottis is opened, and air is forced from the lungs across the open glottis. In the case of ejectives, a glottal constriction is also made simultaneously with an oral constriction; but is released after the release of the oral constriction. So ejectives involve a rearrangement in time of the constrictions needed to produce glottally reinforced voiceless plosives.

Another explanation for ejectives in English lies in the fact that the plosive release of ejectives is typically loud (or at least louder than the release of the corresponding pulmonic sound): this enhances the audibility of the burst, and makes it easier to perceive the place of articulation of the plosive.

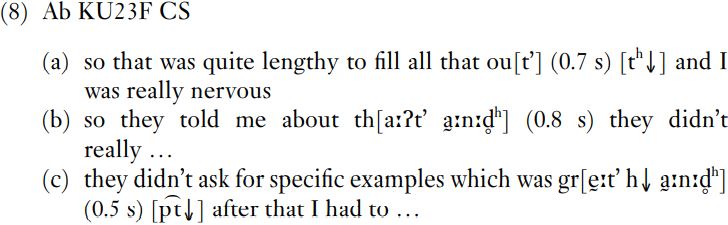

Here are some examples of ejectives taken from a narrative by a woman from Aberdeen in her early twenties. She is telling about applying for a job. (Timings between brackets within transcriptions mark pauses in the speaker’s talk; e.g. (0.5 s) means the speaker is not talking for 0.5 seconds.)

The ejectives here all come in the context of a pause in her talk, either immediately or shortly after the ejective. In (a), the ejective comes before a pause, which is exited with an audible percussive alveolar release, followed immediately by an in-breath (marked here with  ). In (c) too, there is an in-breath just after the ejective. In (b) and (c), the ejective is followed by a long production of ‘and’ which starts with creaky voice: we might expect creak after a glottal closure, as the vocal folds start to vibrate modally again. In all these cases, the speaker continues speaking after the stretch which contains the ejective.

). In (c) too, there is an in-breath just after the ejective. In (b) and (c), the ejective is followed by a long production of ‘and’ which starts with creaky voice: we might expect creak after a glottal closure, as the vocal folds start to vibrate modally again. In all these cases, the speaker continues speaking after the stretch which contains the ejective.

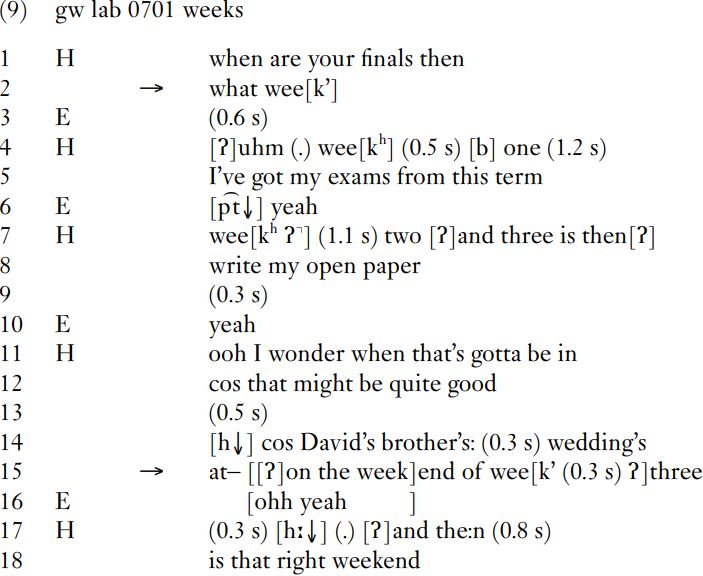

In the extract in (9) below, a conversation between two students from the north of England, there are two ejectives: one turn-finally, the other in the middle of a turn.

The turn-final ejective is in line 2, a reformulation of a question (line 1) which makes it more specific what kind of answer is required (a reference to which week in term, rather than, e.g. a calendar date like ‘15 June’). This one is at a place in the conversation where the other person can be expected to talk next.

The turn-medial one comes in line 15 between the words ‘week’ and ‘three’, which is part of a list (week one, week two, week three). Although the word ‘three’ is highly predictable from the context, there is a hitch in the speaker’s production, and the ejective occurs before a 0.2-s pause.

In line 15, in between the release of the plosive of ‘week’ and the start of the friction of ‘three’ is a pause of about 0.3 s. The fricative [f ] at the start of ‘three’ starts with a glottal stop. So the glottal closure made earlier at the same time as the velar closure in ‘week’ is held until the speaker starts to speak again with ‘three’. Articulations which are held across gaps in speaking within a speaker’s turn like this have been shown for English to mark: ‘I may not be speaking now but I have more to say and I am keeping the turn’. So perhaps the ejective in this environment is a side-effect of some other work that is being done by a glottal stop.

We can compare Helen’s production of ‘week’ here with her other productions of ‘week’ in lines 4 and 7. In line 4, the plosive is produced with aspiration, followed by a long pause. There is evidently labial closure too: the word ‘one’ is preceded by a bilabial plosive with approximately 0.07 s of voicing during the closure. In line 7, the plosive at the end of ‘week’ is produced with lengthy aspiration (0.45 s), which is abruptly cut off by a glottal stop before a pause of 1.1 s. The pause is released into an alveolar plosive.

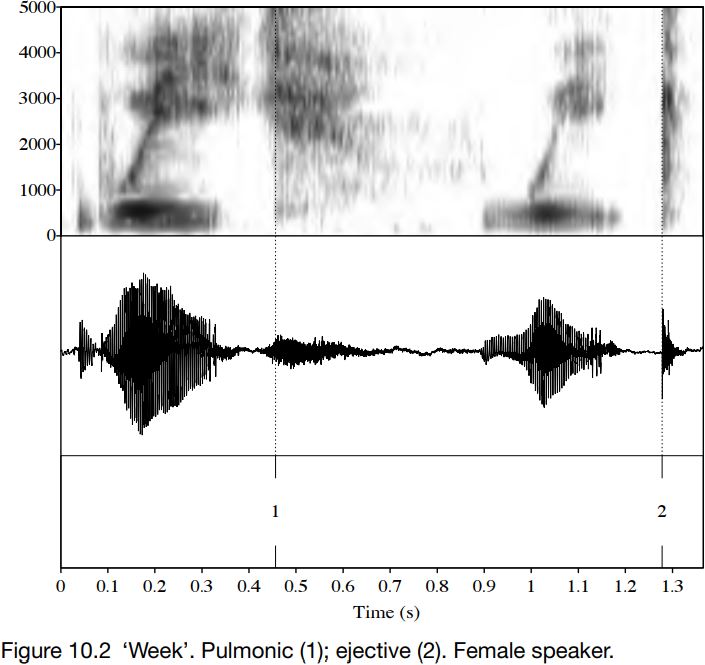

For comparison, spectrograms of the tokens of ‘week’ from lines 4 ([k]) and 15 ([k’]) are shown in Figure 10.2.

The first production (on the left) shows voicelessness and closure cooccurring: notice the high-frequency friction around 3000–4000 Hz between 0.3 and 0.4 s on the spectrogram. The plosive is released with a considerable amount of aspiration: the release is marked at 1 on the spectrogram. The second production is an ejective production, marked at 2 on the spectrogram. Notice the glottal closure at around 1.15 s, and the very abrupt way that the energy for the vowel dies away. The plosive release marked at 2 is sharp and loud (darker than at 1), and although there is some friction noise, it is much shorter in duration than in the pulmonic production. This is because the amount of air available between the glottal and velar closures is rather small, which makes it difficult for friction to be sustained for very long; whereas for pulmonically initiated productions, there is far more air in the lungs which can be forced out to produce aspiration noise.

So while not all the tokens of ‘week’ contain ejectives in this fragment, they do all have some kind of closure which is held in the pause after the word ‘week’, and two of these, in lines 7 and 15, involve also glottal closure. In making sense of the distribution of ejectives, then, we probably need to look at the wider context. This way, we can see the ejectives as part of a longer stretch of phonetic events, which includes a plosive, a pause, and an exit from the pause.

الاكثر قراءة في Phonetics

الاكثر قراءة في Phonetics

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام) قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر مجموعة قصصية بعنوان (قلوب بلا مأوى)

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر مجموعة قصصية بعنوان (قلوب بلا مأوى)