Clicks in English

Clicks can be produced at a range of places of articulation. In English, the commonest ones are probably bilabial, alveolar lateral and dental.

Bilabial clicks, when produced with pursed lips, resemble a peck on the cheek. These clicks are used to mimic kissing (or even done instead of kissing, as in the stereotyped ‘mwah!’ of insincerely warm greetings). Lateral clicks are sometimes used to ‘gee up’ horses (and usually come in pairs).

The dental click is so ubiquitous in English that we even have a verb to describe making it: ‘tutting’. Stereotypically, we associate this with an expression of disapproval (accompanied in our mind’s eye by rolling one’s eyes heavenwards). In the next few paragraphs, we look at some instances of [J] taken from naturally occurring English conversation.

We start with an example of a click used as part of a response to a story. Lesley has been telling Joyce about a visit to a church fair. At this fair, an acquaintance of theirs said something Lesley finds offensive, and which she has taken delight in telling Joyce about. At lines 2–3, Lesley directly quotes this acquaintance and brings his objectionable behavior to the fore in the punchline of the story.

Joyce’s immediate reaction to the punchline at line 4 is a dental click followed by an open vocalic gesture accompanied by ingressive airflow. This is a display of understanding of Lesley’s story: a complaint about the behavior of their acquaintance. The click is only the beginning of the sequence of talk in which Joyce and Lesley complain about him, and Joyce’s turn continues with an assessment of this acquaintance as ‘dreadful’.

Perhaps it is significant that both the click and the vowel sound that come after it are ingressive: having air in the lungs is a prerequisite for talking, and in-breaths are often used to mark: ‘I have more to say’. Sharp in-breaths are also a reflex reaction to unexpected physical events: perhaps the in-breath here is an iconic device to express ‘shock’ – although it is unlikely to be a spontaneous shock, since the story has been constructed to achieve precisely this response.

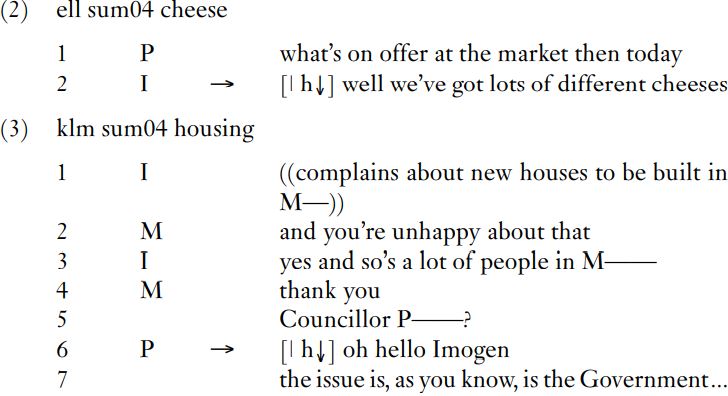

Clicks can also be used to initiate turns at talk in less emotionally charged contexts, as in the following cases:

In (2), the click in line 2 prefaces the answer to a question; in (3), the click in line 6 starts Councillor P’s response to I’s point, having been selected as the next speaker in line 5 by M.

Again the clicks are followed by ingressive airflow, this time an in-breath (marked in the transcripts as [h↓]). In these cases, the clicks do not seem to ‘express disapproval’. Rather, they seem to be used to project more talk by the speaker, i.e. to mark ‘I have more to say’.

Clicks can be used as part of turns that display other kinds of stance. For example, they can occur at the start of turns that mark some display of sympathy. In the example below, Agnes complains about the weekend she has had. In response to this telling, Billie produces a click followed by a long and creaky  . The click is produced on beat with a rhythm established by Agnes: the stars above lines 2 and 3 mark the beats, which are evenly spaced in time.

. The click is produced on beat with a rhythm established by Agnes: the stars above lines 2 and 3 mark the beats, which are evenly spaced in time.

Billie comes in at line 3 before the completion of Agnes’s turn ‘what a miserable miserable weekend’ with a click. Agnes and Billie both continue their talk on beat (i.e. they talk in overlap), Agnes producing the completion of her turn, ‘weekend’, Billie producing a long, creaky open vowel. Since the rhythm was established by Agnes, we could interpret Billie’s use of it to time her talk as a display of attention to the details of Agnes’s talk, and in doing that, going along with the complaint made by Agnes. This is consistent with her display of sympathy in her next turn: ‘that’s a shame’. So here we have a click which seems to be produced as the first part of a display of sympathy with another’s situation, and which seems to be temporally placed to display attentiveness to that other person’s telling of the situation.

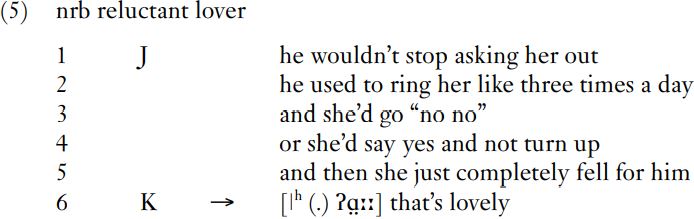

Clicks can also be used to mark receipt of positive news. In the next fragment, Jade tells Kate how two people they know became a couple. Once she has completed her story, Kate offers an appreciation of the story (line 6), which starts with a click followed by a long, breathy open vowel with falling pitch. If clicks marked ‘disapproval’, then Kate would be treating this story as bad news; but in fact she makes a positive assessment of the story: ‘that’s lovely’. Indeed, we might even say that the stretch  marks a positive receipt of the news.

marks a positive receipt of the news.

So, here we have a few instances where clicks initiate turns that provide assessments or appreciations of a telling; in these turns, the recipient of a story demonstrates their understanding of the kind of story it was, which can include ‘disapproval’, but also ‘a story deserving of sympathy’ and ‘good news’.

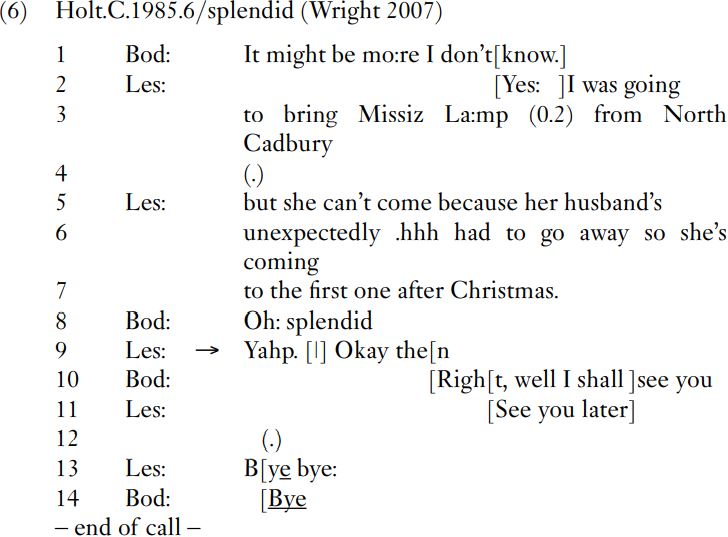

Another common use for clicks is to signal the transition from one activity to another (Wright 2007). A good place to observe this is at the end of phone calls, where there is a sequence that English speakers commonly use to manage how they will both get to the point of putting the phone down. (This may seem trivial, but putting the phone down before it is due is a big faux pas in English-speaking societies.) The fragment in (6) below displays this well. The current topic is closed down in lines 8–9 (‘oh splendid’/‘yahp’); then there follows a click in line 9; then there is a short sequence in lines 9–10 where a proposal is made to close the call (‘Okay then’), which is accepted (‘right’), and then greetings are exchanged, and the speakers hang up the phone. Clicks are common in this sequence in between the closing down of the topic and the ‘OK’:

The click occurs in a single turn which has two parts. The first part, ‘yahp’, closes down the earlier sequence about Mrs Lamp’s attendance at a meeting. The second part of the sequence, ‘Okay then’, marks the beginning of the closing of the call (‘Okay then/right’, after which the speakers start to exchange greetings). The click marks the transition between two activities.

While we commonly find velarically initiated clicks in turns like this, we also find other kinds of ingressive sounds and percussives: the most usual are audible lip smacks or releases of other closures, where the articulators are separated from one another, which may produce a sound loud enough to be heard. If the speaker breathes in loudly enough to be heard, this can sound like e.g. an ingressive voiceless bilabial plosive, [p↓]. It is perhaps an important feature of clicks in these particular sequences that they stand in free variation with other (related) sounds; whereas the clicks that express some kind of stance are not, and cannot be, produced in this way, but must be velarically initiated.

The clicks we have looked at so far are all accompanied by [k] and then sometimes followed by a vocalic articulation which is either ingressive or egressive. The next, and final, example of a click is accompanied by voicing and nasality,  . In this example, the click occurs at the start of the receipt of a compliment.

. In this example, the click occurs at the start of the receipt of a compliment.

(In line 6, (*) marks an indistinct syllable.) Kate has dyed her hair red, and Jade has been complimenting her on it. In line 5, Kate produces a nasalized click with a breathy-voiced and long open vowel, with a pitch contour that falls from high to low in her range. It is immediately followed by ‘thank you’. The commonest lay interpretation of clicks, ‘disapproval’, is once again unlikely to be what Kate does in line 5.

In summary then, we can find a range of clicks in naturally occurring spoken English. Their distribution and functions are not well researched; but they seem to occur at the start of turns, or to mark the transition from one kind of activity to another within a turn. They commonly seem to be involved in assessing stories or situations, but (contrary to English speakers’ general intuitions) they do not necessarily imply ‘disapproval’, or even anything negative at all.

الاكثر قراءة في Phonetics

الاكثر قراءة في Phonetics

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة