Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension| Reflection: “He-Said-She-Said” in African-American Vernacular English (AAVE) and recursivity in reporting talk |

|

|

|

Read More

Date: 1-6-2022

Date: 6-5-2022

Date: 26-4-2022

|

While at their most basic level metarepresentations involve embedding a meaning representation relative to another meaning representation, these initial metarepresentations can be further embedded within other metarepresentations. This embedding is termed recursivity. The potential for recursive embedding of representations means that instances of reported talk, for example, can involve multiple levels of representations.

Consider, for instance, the practice termed “He-Said-She-Said” that is claimed to occur in AAVE (Goodwin 1990), particularly in disputes about gossip amongst pre-adolescent, working class African-American girls. The practice involves one participant accusing another participant of talking “behind her back”. More specifically, the accuser uses “a series of embedded clauses to report a series of encounters in which two girls were talking about a third” (Goodwin and Goodwin 2004: 232). In the example below, taken from recordings of conversations between some African-American girls, Annette is accusing Benita of talking behind her back:

Annette implicates this accusation by reporting on what Tanya has said Benita had previously said. It involves a complex form of recursive quotation where Annette is speaking to Benita about what Tanya told Annette (and Tanya said) that Benita said to Tanya (that you said) about Annette (that I was showing off just because I had that blouse on). Hence the term “He-Said-She-Said” or, to be more precise in this case, “SheTanya-Said-SheBenita-Said”. This involves, from a metapragmatic perspective, a metarepresentation embedded within a higher-order metarepresentation. That is:

[a higher-order utterance] about [an attributed higher-order utterance]2 about [an attributed lower-order utterance]

The use of recursive quotation is not, of course, unique to pre-adolescent, working class African-American girls. But it is used here in a specific way, namely, as a response to situations where an “instigator” (here Tanya) tells someone (Annette) that another girl (Benita) has been talking about her behind her back. The He-Said-She-Said practice is thus not only a way for someone to hold another person to account for gossiping behind her back about her (or him), but also to implicate yet another person as the source of this accusation. It therefore becomes a way of establishing schisms and alliances within what is ostensibly a group of friends.

One challenge facing the Relevance theoretic account of irony as echoic, however, is the relationship between the examples of utterance-based verbal irony that they generally analyze, and instances of situational irony. The latter is generally understood to involve some kind of incongruity between what might be expected and what actually occurs. Littman and Mey (1991) and Clift (1999) have both argued that any account of irony should be able to deal with all kinds of irony, not just verbal irony à la relevance theory. Let us consider for a moment the rather savage situational irony that arises in the following news report that originated from an international news agency based in the US:

[8.8]

A man ended up in hospital after ordering a Triple Bypass burger at the Heart Attack Grill, a Las Vegas restaurant that jokingly warns customers “this establishment is bad for your health.”

Laughing tourists were either cynical or confused about whether the man was really suffering a medical episode amid the “doctor,” “nurses” and health warnings at the Heart Attack Grill, restaurant owner Jon Basso said yesterday.

“It was no joke,” said Basso

Giggles can be heard on the soundtrack of amateur video showing the man on a stretcher being wheeled out of the restaurant where patrons pass an antique ambulance at the door and a sign: “Caution! This establishment is bad for your health.”

Eaters are given surgical gowns as they choose from a calorically extravagant [cf. calorie-extravagant] menu offering “Bypass” burgers, “Flatliner” fries, buttermilk shakes and free meals to folks over 350 pounds [cf. 159kg]. Another sign on the door reads, “Cash only because you might die before the check clears.”

(“Bypass burger lives up to its name”, Associated Press, 17 February 2012)

Multiple layers of irony arise in the above excerpt from the news report. First of all, we have the ironic status of the place in question. The name of the restaurant (the Heart Attack Grill), its menu (Triple Bypass burger, Flatliner fries, etc.), the explicit warnings (this establishment is bad for your health), and the associated surroundings (e.g. having workers dressed as health care workers) all constitute potential instances of irony. They all echo in various ways general warnings that we have all heard about the negative impact that excessive consumption of fast food, such as the burgers and fries served at that restaurant, can have on our health. In echoing these warnings with exaggerated formulations, the restaurant management is echoing these warnings (which are attributable to the medical establishment and government bodies) with a dissociative attitude, more specifically, a kind of defiant skepticism or even mockery, and encouraging their customers to take a similar stance.

The second layer of irony arises from the primary focus of the news report, namely, that a customer at the restaurant fell ill and was taken to hospital after ordering a Triple Bypass burger. Notably, it is implicated through the formulation of the leading sentence that the man might have ended up in hospital because of ordering that burger (i.e. “A after B” implicates “A because of B”). It is, of course, moving into the realm of the ludicrous to even suggest this, but therein lies the situational irony: a man was taken ill in a place that ironically mocks health warnings about fast food. The incongruity arises from a man falling ill (what actually occurred) in a restaurant that appeared confident enough to take an ironic stance on such a possibility (i.e. what appeared to be expected is that no one would ever really fall ill from the food, at least not there in the actual restaurant). The headline of the report plays on this situational irony (Bypass burger lives up to its name), by wryly echoing the ironic stance of the restaurant.

The third, and perhaps most savage, layer of irony arises from the report about the response of other customers to the man falling ill, namely, that some of them treated it as a laughing matter. Once again we have an instance of situational irony as there is a clear incongruity between what might be expected in such a situation (i.e. that no one would treat someone falling ill as a joke) and what actually occurred (i.e. some customers treated it as a joke). As a reader of the news report, we are, of course, privy to all these multiple instantiations of irony. What is significant here is that echoic irony, of the kind described by Relevance theorists, is interwoven with situational irony, for which they do not offer an explicit account. However, it is worth noting that their general claim nevertheless stands, namely, that metarepresentations lie at the heart of irony, and that irony inevitably involves some kind of dissociative attitude.

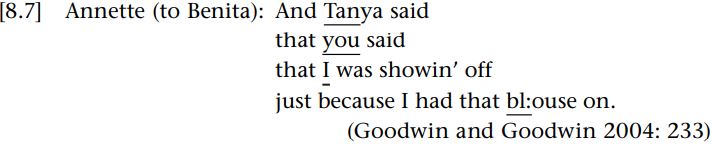

In summary, then, metarepresentational awareness involves reflexive representations of the intentional states and utterances of participants, as illustrated in Figure 8.2. Reported talk involves, at minimum, a first-order metapresentation (e.g. an utterance about another attributed utterance), while irony involves, at minimum, a second-order metarepresentation (e.g. an attitude expressed about an utterance about an attributed intentional state). However, these metarepresentations can be further embedded in other metarepresentations as we saw in the case of He-Said-She-Said or in the report on the incident at the Heart Attack Grill. In the latter case, for instance, the name of the restaurant is assumed to echo general health warnings (first-order metarepresentation), about which customers are assumed to have a wry or dismissive attitude (second-order metarepresentation), but which is then quoted in a news report in light of their confused response to a person who was reported as falling seriously ill in that restaurant (third-order metapresentation), and towards which the writer presumably has a mocking, or at least wry, attitude (fourth-order metarepresentation), which we the readers attribute to that publisher, and may or may not entertain ourselves (fifth-order metarepresentation).

In other words, both instances of echoic and situational irony, as well as reported talk/conduct, arise in the course of we, the readers, attributing to the publisher or writer of the report an attitude towards the customer’s allegedly confused response in light of their presumed attitude towards the warnings and name of the restaurant that (ironically) echo general health warnings. In theory, metarepresentations can be extended to the nth order. In practice, they normally become to become too complex for users to process, or at least to talk about, at around the fifth or sixth order of metarepresentation.

|

|

|

|

علامات بسيطة في جسدك قد تنذر بمرض "قاتل"

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

أول صور ثلاثية الأبعاد للغدة الزعترية البشرية

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

وفد كلية الزراعة في جامعة كربلاء يشيد بمشروع الحزام الأخضر

|

|

|