Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension|

Read More

Date: 19-2-2022

Date: 17-5-2022

Date: 23-5-2022

|

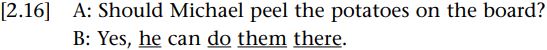

Anaphoric expressions refer to a previously expressed textual unit or meaning, the so-called antecedent. Anaphora, in the context of linguistics, is generally understood to refer to “a relation between two linguistic elements, wherein the interpretation of one (called an anaphor) is in some way determined by the interpretation of the other (called an antecedent)” (Huang 2000: 1). It may be helpful to know that the term anaphora is derived from the Greek word αναφορα, meaning “carrying back”. Here is an example:

The anaphoric expressions in B’s utterance and their antecedents are as follows: he (Michael), do (peel), them (the potatoes) and there (on the board). The fact that both the anaphoric expressions and their antecedents refer to the same entities – they are co-referential – is a characteristic of many anaphora, but not of deixis. This is not to say that there is no overlap with deixis. Readers will have noted that the form there is also used as a deictic expression. Indeed, in B’s utterance one could imagine a scenario in which there is used not only to refer back to on the board but to pick out deictically the particular board to be used (the speaker could simultaneously point). Expressions functioning anaphorically comprise most frequently third person pronouns (e.g. he) and repeated or synonymous noun phrases (e.g. B in the above example could have repeated “the potatoes”), but also, for example, other definite noun phrases (including pronouns, demonstratives such as those, proper nouns), pro-forms (e.g. do) and adverbs (e.g. there). To this list we might add the absence of an expression where it is expected, a “gap” in the syntax. A typical example is the absence of the second finite verb in co-ordinated structures, such as: She took kindly to him, and he [took kindly] to her (BNC G0M 1282, prose fiction, the novel The Holy Thief). Needless to say, the resources available for expressing anaphoric reference vary from language to language. For example, some languages (e.g. Salt-Yui, a Papuan language) lack third person pronouns, deploying full nominal expressions instead (Siewierska 2004: 6, who cites Irwin 1974).

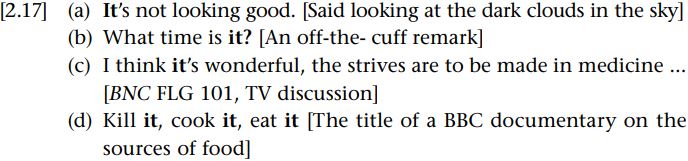

As one might guess, even typical anaphoric expressions are not always anaphoric and do not always refer, at least not straightforwardly. Consider these examples, all of which concern the third person singular pronoun:

It in (a) has no textual antecedent. It is not anaphoric but most obviously a deictic usage: it points to the particular state of the sky. Halliday and Hasan ([1976] 1997) label uses that rely on something outside the text for their interpretation exophoric, a category which contrasts with endophoric, which includes uses that rely on something inside the text. It in (b) is similar to (a),– it has no textual antecedent. However, although it also involves the extralinguistic context, and thus is exophoric, it is not picking out something specific in the situational context in which it is said, as would be the case with deixis. Instead, it is an empty or dummy subject referring to an aspect of the context of the utterance that can readily be inferred. Dummy subjects (or objects) such as this are often used to refer to very general contextual aspects of utterance, notably, relating to time, distance (e.g. how far is it to Lancaster) or weather (e.g. it’s nice and warm) (Biber et al. 1999: 332). Halliday and Hasan (1997) label such uses homophoric. It in (c) is similar to an anaphoric usage, but in this case it is referring forward to the textual segment the strives are to be made in medicine (by the unusual noun “strives” the speaker presumably means the things that can be successfully striven for). Such uses are termed cataphoric (Halliday and Hasan 1997). Finally, the point of interest regarding (d) is that each instance of it is co-referential, that is, each refers to the same entity. Except that they do not quite. The animal that is killed is not identical to the animal that is cooked and is eventually eaten. But of course, the point of this title is to make it clear that we are anaesthetized to the realities of eating meat by the fact that we only encounter “it” as prepared food in supermarkets.

|

|

|

|

علامات بسيطة في جسدك قد تنذر بمرض "قاتل"

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

أول صور ثلاثية الأبعاد للغدة الزعترية البشرية

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

مكتبة أمّ البنين النسويّة تصدر العدد 212 من مجلّة رياض الزهراء (عليها السلام)

|

|

|