Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Floating tones

المؤلف:

David Odden

المصدر:

Introducing Phonology

الجزء والصفحة:

294-9

14-4-2022

3301

Floating tones

Another tonal phenomenon which confounds the segmental approach to tone, but is handled quite easily with autosegmental representations, is the phenomenon of floating tones, which are tones not linked to a vowel.

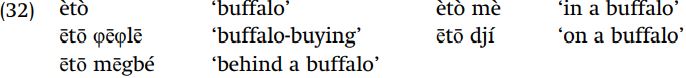

Anlo tone. The Anlo dialect of Ewe provides one example. The data in (32) illustrate some general tone rules of Ewe. Underlyingly the noun ‘buffalo’ is /ētō/, with M tone on its two vowels. However, it surfaces as [ètò] with L tones, either phrase-finally or when the following word has an L tone.

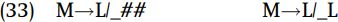

These alternations are explained by two rules; one rule lowers M (mid) to L at the end of a phrase, and the second assimilates M to a following L.

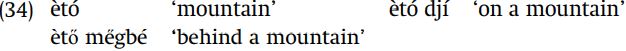

Thus in the citation form, /ētō/ first becomes ētò, then [ètò]. Two other tone rules are exemplified by the data in (34).

Here, we see a process which raises M to Superhigh tone (SH) when it is surrounded by H tones; subsequently a nonfinal H tone assimilates to a preceding or following SH tone.

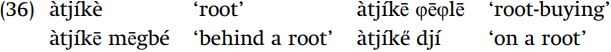

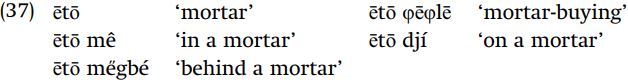

We know from ētō mēgbé ‘behind a buffalo’ that mēgbé has the tones MH. Therefore, the underlying form of ètő me̋gbé ‘behind a mortar’ is ètó mēgbé. The underlying form is subject to the rule raising M to SH since the M is surrounded by H tones, giving ètó me̋gbé. This then undergoes the SH assimilation rule. Another set of examples illustrating these tone processes is (36), where the noun /àtjíkē/ ends in the underlying sequence HM. When followed by /mēgbé/, the sequence HMMH results, so this cannot undergo the M-raising rule. However, when followed by /dyí/, the M-raising rule applies to /kē/, giving an SH tone, and the preceding syllable then assimilates this SH.

There are some apparently problematic nouns which seem to have a very different surface pattern. In the citation form, the final M tone does not lower; when followed by the MM-toned participle /φēφlē/, the initial tone of the participle mysteriously changes to H; the following L-toned post-position mè inexplicably has a falling tone; the postposition /mēgbé/ mysteriously has an initial SH tone.

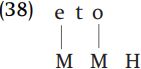

All of these mysteries are resolved, once we recognize that this noun actually does not end with an M tone, but rather ends with an H tone that is not associated with a vowel, thus the underlying form of the noun ‘mortar’ is (38).

Because this noun ends in a (floating) H tone and not an M tone, the rule lowering prepausal M to L does not apply, which explains why the final tone does not lower. The floating H at the end of the noun associates with the next vowel if possible, which explains the appearance of an H on the following postposition as a falling tone (when the postposition is mono-syllabic) or level H (when the next word is polysyllabic). Finally, the floating H serves as one of the triggering tones for the rule turning M into SH, as seen in ētō me̋gbé. The hypothesis that this word (and others which behave like it) ends in a floating H tone thus provides a unified explanation for a range of facts that would otherwise be inexplicable. However, the postulation of such a thing as a “floating tone” is possible only assuming the autosegmental framework, where tones and features are not necessarily in a one-to-one relation.

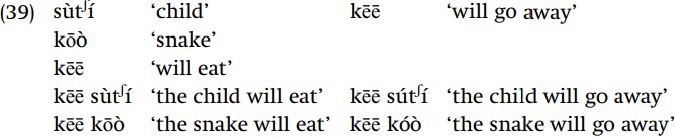

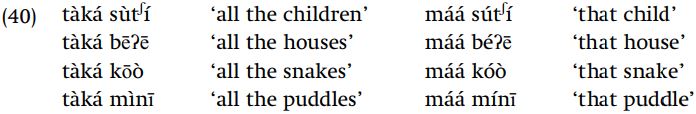

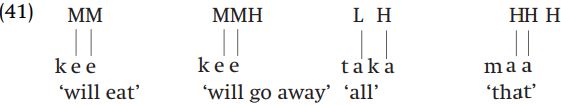

Mixtec. Another example of floating tones can be seen in the language Mixtec. As (39) indicates, some words such as kēē ‘will eat’ have no effect on the tone of the following word, but other words such as the apparently homophonous verb meaning ‘will go away’ cause the initial tone to become H.

A similar effect is seen in (40), where tàká ‘all’ has no effect on the following word, but máá ‘that’ causes raising of the initial tone of the next word.

These data can be explained very easily if we assume the following underlying representations.

When a word ending in a floating H tone, such as ‘will go away’ or ‘that’, is followed by another word, that H associates to the first vowel of the next word and replaces the initial lexical tone. When there is no following word, the floating tone simply deletes.

Gã. Other evidence for floating tones comes from Gã. Some of the evidence for floating L tone in this language involves the phenomenon of “downstep,” which is the contrastive partial lowering of the pitch level of tones at a specified position. Downstep is exemplified in Gã with the words [kɔ̀ tɔ́ kɔ̀ ] ‘porcupine,’ [ònũf́ ũ]́ ‘snake,’ and [átá! tú] ‘cloud.’ In ‘porcupine,’ the syllable [tɔ́ ] has H and the following syllable [kɔ̀ ] has L – the physical pitches are maximally separate. The second and third syllables of ‘snake’ are both H and are not physically distinct – they are produced at the same pitch, at the top of the voice range. In the third example, the syllable [tá] has the same high pitch that all of the second syllables of these words have, and the following syllable, which is phonologically H-toned, has a pitch physically between that of the L-toned syllable of [kɔ̀ tɔ́ kɔ̀ ] and the Htoned syllable of [ònṹfṹ]. What happens here is that the pitch range of all tones is lowered after the second syllable of [átá! tú], even those of a following word. This lowering of pitch range, notated with “! ”, is known as “downstep.” A floating L between H tones is what in fact generally causes downstep.

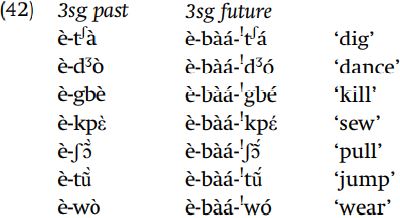

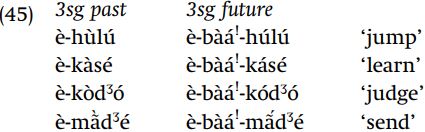

In Gã, there is a rule changing the tone sequence HL before pause into H! H. The operation of this rule can be seen in the data of (42), where the presence of the future tense prefix -bàá- causes a change in the tone of final L-toned verbs with the shape CV (the unmodified tone of the root is seen in the 3sg past form).

The necessity of restricting this rule to HL before pause is demonstrated by examples such as èbàágbè Àkò ‘he will kill Ako,’ èbàákpὲ àtààdé ‘he will sew a shirt,’ èbàáʃɔ̃ ̀ kpàŋ ‘he will pull a rope.’ In such examples, the tone sequence is not prepausal, and the underlying L is retained in phrase-medial position, whereas the verb has !H tone in prepausal position in (42).

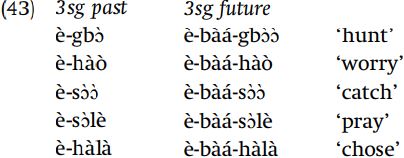

The restriction to applying just to prepausal HL also explains why verbs with long vowels or two syllables do not undergo this alternation: the L-toned syllable that comes after the H is not also at the end of the phrase, since another L tone follows it.

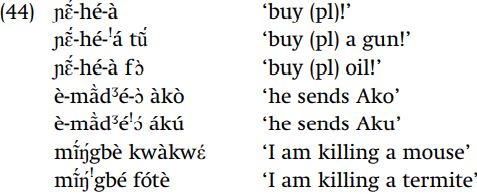

A further restriction is that this rule does not apply to tense-inflections on verbs, for example the plural imperative -à ( ɲɛ̃ ́-hé-à ‘buy (pl)!’) or the habitual -ɔ̀ (è-mã̀dʒ é-ɔ̀ ‘he sends’).

A second relevant rule of Gã is Plateauing, whereby HLH becomes H! HH. This can be seen in (44) involving verbs with final HL. If the following word begins with L tone, the final L of the verb is unchanged. When the following object begins with an H tone, the resulting HLH sequence becomes H! HH by the Plateauing rule.

This rule also applies within words, when the verb stem has the underlying tone pattern LH and is preceded by an H-toned prefix, such as the future prefix.

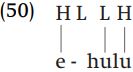

Again, by the Plateauing rule, /è-bàá-hùlú/ becomes [è-bàá! -húlú].

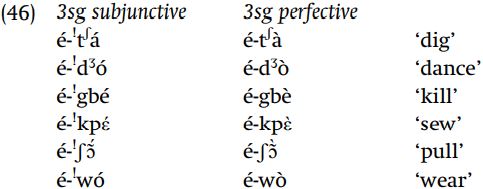

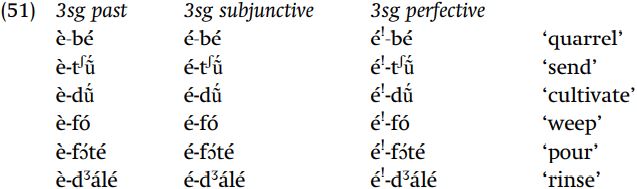

There are a number of areas in the language where floating tones can be motivated. The perfective tense provides one relevant example. Consider the data in (46), which contrasts the form of the subjunctive and the perfective. Segmentally these tenses are identical: their difference lies in their tone. In both tenses the subject prefix has an H tone. In the perfective, the rule affecting prepausal HL exceptionally fails to apply to an L-toned CV stem, but in the subjunctive that rule applies as expected.

You might think that the perfective is an exception to the general rule turning HL into H! H, but there is more to it.

Another anomaly of the perfective is that the Plateauing rule fails to apply between the verbs of (46) and the initial H tone of a following word, even though the requisite tone sequence is found.

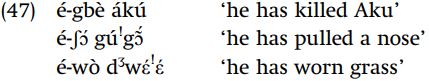

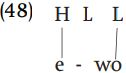

The failure of both the HL ! H! H rule and the Plateauing rule can be explained by positing that the perfective tense is marked by a floating L tone which comes between the subject prefix and the verb stem; thus the phonological representation of perfective é-wo would be (48), and we can identify a L tone which has no assciated vowel as being the morpheme marking the perfective.

The floating L between the H and the L of the root means that the H is not next to the prepausal L, and therefore the rule changing HL into H! H cannot apply. In addition, the presence of this floating L explains why this verb form does not undergo Plateauing. Thus two anomalies are explained by the postulation of a floating L tone.

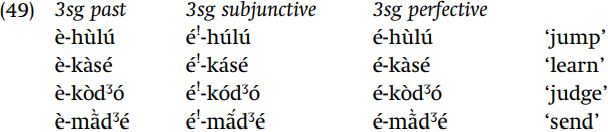

Other examples of the failure of the Plateauing rule in this tense can be seen below. The examples from the simple past show that these verb roots underlyingly have the tone pattern LH, which surfaces unchanged after the L-toned subject prefix used in the simple past. The subjunctive data show that these stems do otherwise undergo Plateauing after an H-toned prefix; the perfective data show that in the perfective tense, Plateauing fails to apply within the word, because of the floating L of the perfective Again.

These facts can be explained by positing a floating L tone in the perfective tense: that L means that the actual tone sequence is HLLH, not HLH, so Plateauing would simply not be applicable to that tone sequence.

Finally, the postulation of a floating L as the marker of the perfective explains why a downstep spontaneously emerges between the subject prefix and a stem-initial H tone in the perfective, but not in the subjunctive.

Thus the postulation of a floating tone as the marker of the perfective explains a number of anomalies: insofar as floating tones have a coherent theoretical status in autosegmental phonology but not in the linear theory, they provide strong support for the correctness of the autosegmental model.

الاكثر قراءة في Phonology

الاكثر قراءة في Phonology

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)