Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Basic Maltese phonology

المؤلف:

David Odden

المصدر:

Introducing Phonology

الجزء والصفحة:

260-8

9-4-2022

2072

Basic Maltese phonology

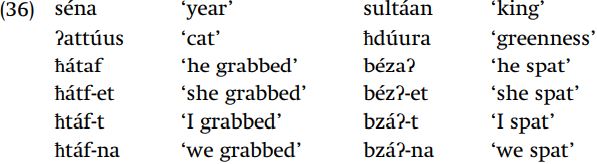

Stress and apocope. (36) examplifies two central processes of the language, namely stress assignment and apocope. Disregarding one consonant at the end of the word, the generalization is that stress is assigned to the last heavy syllable – one that ends in a (nonfinal) consonant or one with a long vowel.

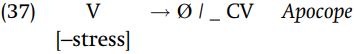

The second group illustrates apocope, which deletes an unstressed vowel followed by CV. The underlying stem of the word for ‘grabbed’ is /ħataf/, seen in the third-singular masculine form. After stress is assigned in third-singular feminine /ħátaf-et/, (37) gives surface [ħatf-et].

In /ħataf-t/ stress is assigned to the final syllable since that syllable is heavy (only one final consonant is disregarded in making the determination whether a syllable is heavy), and therefore the initial vowel is deleted giving [ħtáft]

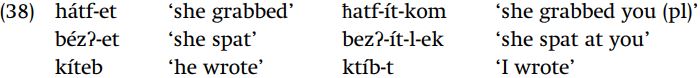

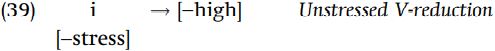

Unstressed reduction and harmony. Two other rules are unstressed-vowel reduction and vowel harmony. By the former process, motivated in (38), unstressed i reduces to e. The third-singular feminine suffix is underlyingly /-it/, which you can see directly when it is stressed. The underlying form of kíteb is /kitib/. When stress falls on the first syllable of this root, the second syllable reduces to e, but when stress is final, the second syllable has i.

Thus the following rule is motivated

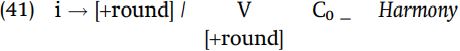

By vowel harmony, /i/ becomes [o] when preceded by o.

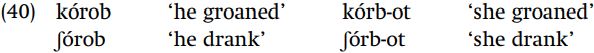

Surface kórb-ot derives from /korob-it/ by applying stress assignment, the vowel harmony in (41), and apocope.

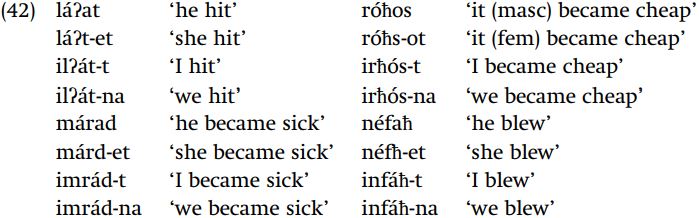

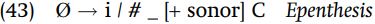

Epenthesis. The data in (42) illustrate another rule, which inserts [i] before a word-initial sonorant that is followed by a consonant.

Stress assignment and apocope predict /laʔat-na/ -> lʔát-na: the resulting consonant cluster sonorant plus obstruent sequence is eliminated by the following rule:

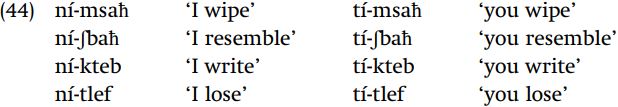

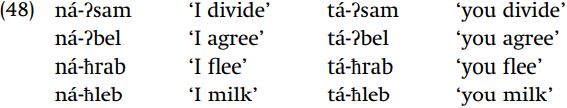

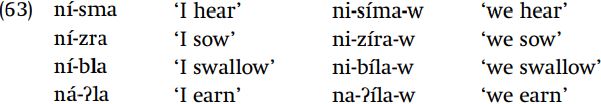

Regressive harmony and precoronal fronting. These rules apply in the imperfective conjugation, which has a prefix ni- ‘1st person,’ ti- ‘2nd person’

or ji- ‘3rd person’ plus a suffix -u ‘plural’ for plural subjects. The underlying prefix vowel i is seen in the following data:

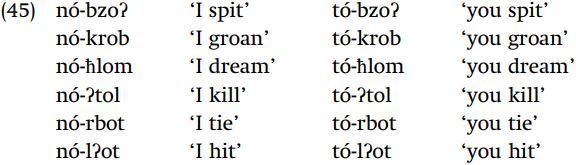

When the first stem vowel is o, the prefix vowel harmonizes to o:

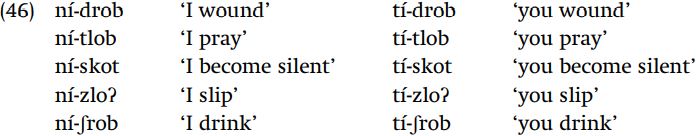

This can be explained by generalizing harmony (41) so that it applies before or after a round vowel. The nature of the stem-initial consonant is important in determining whether there is surface harmony; if the first consonant is a coronal obstruent, there appears to be no harmony.

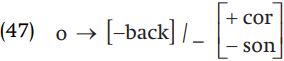

Examples such as nó-bzoʔ show that if the coronal obstruent is not immediately after the prefix vowel, harmony applies. The explanation for apparent failure of harmony is simply that there is a rule fronting o when a coronal obstruent follows.

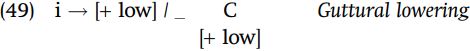

Guttural lowering. Another process lowers /i/ to a before the “guttural” consonants ʔ and ħ:

Treating glottal stop as [+low] is controversial since that contradicts the standard definition of [+low], involving tongue lowering. Recent research in feature theory shows the need for a feature that includes laryngeal glides in a class with low vowels and pharyngeal consonants.

This motivates the following rule:

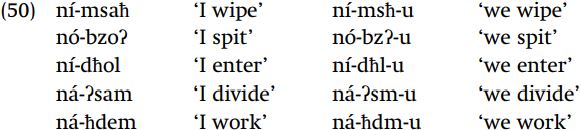

Metathesis. (50) and (51) illustrate another process. When the stem has a medial obstruent, the prefix vowel is stressed and the stem vowel deletes before -u.

This is as expected: underlying /ni-msaħ-u/ is stressed on the first syllable, and the medial unstressed vowel deletes because it is followed by CV. The example [nóbzʔu] from /ni-bzoʔ-u/ shows that harmony must precede apocope, since otherwise apocope would have deleted the stem vowel which triggers harmony.

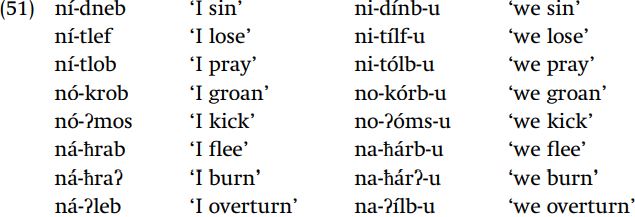

When the second stem consonant is a sonorant, in the presence of the suffix -u the prefix has no stress, and the stem retains its underlying vowel, which is stressed. Unstressed i reduces to [e], so [ní-dneb] derives from /ni-dnib/. The underlying high vowel is revealed when the stem vowel is stressed, as in [nidínbu].

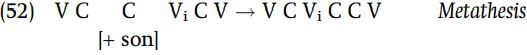

Based solely on stress assignment and apocope, as illustrated in (50), we would predict *nídnbu, *nótlbu. This again would result in an unattested consonant cluster in the syllable onset – a sonorant followed by an obstruent – which is avoided by a process of vocalic metathesis whereby ní-tlif-u ! ni-tílf-u.

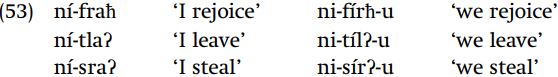

In some stems which undergo (52), the vowel alternates between i and a:

The underlying stem vowel is /i/ in these cases.When no vowel suffix is added, underlying /ni-friħ/ becomes [ní-fraħ] by Guttural Lowering (49). When -u is added, metathesis moves underlying /i/ away from the guttural consonant which triggered lowering, hence the underlying vowel is directly revealed.

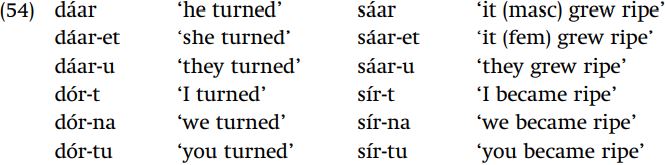

Stems with long vowels. The stems which we have considered previously are of the underlying shape CVCVC. There are also stems with the shape CVVC, illustrated in the perfective aspect in (54):

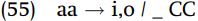

These stems exhibit a process of vowel shortening where aa becomes o or i (the choice is lexically determined) before a CC cluster.

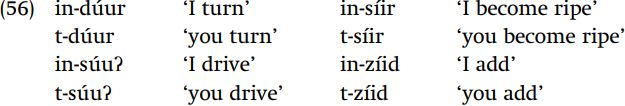

When the imperfective prefixes ni-, ti- are added to stems beginning with a long vowel, stress is assigned to that vowel and the prefix vowel is deleted. In the case of the first-person prefix /ni/, this results in an initial nC cluster, which is repaired by inserting the vowel i.

From /ni-duur/, you expect stress to be assigned to the final syllable because of the long vowel. Since the vowel of /ni/ is unstressed and in an open syllable, it should delete, giving ndúur. The resulting cluster then undergoes epenthesis.

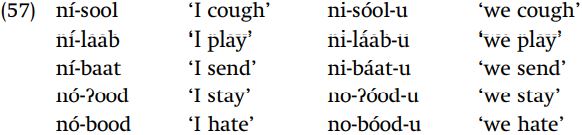

Apparent irregularities A number of verbs seem to be irregular, and yet they are systematic in their irregularity: the irregularity is only in terms of the surface form, which can be made perfectly regular by positing an abstract underlying consonant /ʕ/. One set of examples is seen in the data in (57), where the stem contains a surface long vowel. This long vowel is unexpectedly skipped over by stress assignment, unlike verbs with underlying long vowels such as in-dúur ‘I turn’ seen in (54).

The location of stress and the retention of the prefix vowel in nó-ʔood is parallel to the retention of the prefix vowel in other tri-consonantal stems in (44)–(48), such as ní-msaħ ‘I wipe.’ If the underlying stem of ní-sool had a consonant, i.e. were /sXol/ where X is some consonant yet to be fully identified, the parallelism with ni-msaħ and the divergence from in-dúur would be explained. The surface long vowel in nísool would derive by a compensatory lengthening side effect coming from the deletion of the consonant X in /ní-sXol/.

Another unexpected property of the stems in (57) is that when the plural suffix -u is added, the prefix vowel is stressless and unelided in an open syllable, and the stress shifts to the stem, e.g. ni-sóol-u ‘we cough.’ Thus, contrast ni-sóol-u with ní-msħ-u ‘we wipe,’ which differ in this respect, and compare ni-sóol-u to ni-ʃórb-u ‘we drink,’ which are closely parallel. Recall that if the medial stem consonant is a sonorant, expected V-CRC-V instead undergoes metathesis of the stem vowel around the medial consonant, so /ni-ʃrob-u/ becomes ni-ʃórb-u (creating a closed syllable which attracts stress). If we hypothesize that the underlying stem is /sXol/, then the change of /ni-sXol-u/ to ni-sóXl-u (phonetic nisóolu) would make sense, and would further show that X is a sonorant consonant: ʕ qualifies as a sonorant (it involves minimal constriction in the vocal tract).

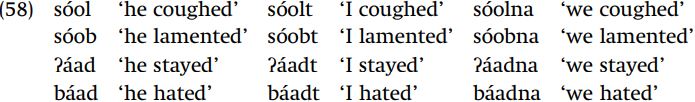

Another pecularity is that these long vowels resist shortening before CC:

In contrast to examples in (54) such as dáar ‘he turned,’ dór-t ‘I turned’ with vowel shortening before CC, these long vowels do not shorten. Continuing with the hypothesis of an abstract consonant in /soXol/, we explain the preservation of the long vowel in [sóolt] if this form derives from sXol-t, where deletion of X (which we suspect is specifically ʕ) lengthens the vowel, and does so after vowel shortening has applied.

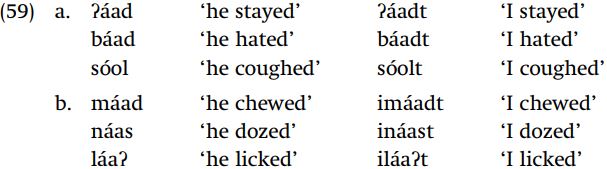

There is a further anomaly in a subset of stems with the consonant X in the middle of the root: if the initial stem consonant is a sonorant, epenthetic i appears when a consonant-initial suffix is added. Compare (59a), where the first consonant is not a sonorant, with (59b), where the first consonant is a sonorant.

The verbs in (59b) behave like those in (42), e.g. láʔat ‘he hit’ ~ ilʔát-t ‘I hit’, where the initial sonorant + C cluster undergoes epenthesis of i. The forms in (59b) make sense on the basis of the abstract forms máʕad ~ mʕádt, where the latter form undergoes vowel epenthesis and then the consonant ʕ deletes, lengthening the neighboring vowel. Before ʕ is deleted, it forms a cluster with the preceding sonorant, which triggers the rule of epenthesis.

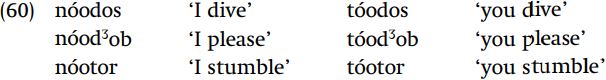

Other mysteries are solved by positing this consonant in underlying forms. In (60), the first stem consonant appears to be a coronal obstruent. We have previously seen that when the stem-initial consonant is a coronal, obstruent vowel harmony is undone (ní-tlob ‘I pray’), so (60) is exceptional on the surface. In addition, the prefix vowel is unexpectedly long, whereas otherwise it has always been short.

These forms are unexceptional if we assume that the initial consonant of the stem is not d, dʒ , t, but the abstract consonant ʕ, thus /ʕdos/, /ʕdʒ ob/, /ʕtor/: ʕ is not a coronal obstruent, so it does not cause fronting of the prefix vowel.

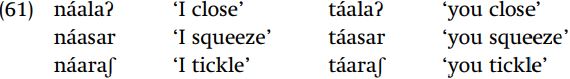

Other examples provide crucial evidence regarding the nature of this abstract consonant. The data in (61) show a lengthened prefix vowel, which argues that the stems underlyingly have the initial abstract consonant that deletes and causes vowel lengthening: [náalaʔ] comes from /ni-ʕlaʔ/.

In addition, the quality of the prefix vowel has changed from /i/ to [aa], even though in these examples the consonant which follows on the surface is a coronal. If the abstract consonant is a pharyngeal as we have hypothesized, then the vowel change is automatically explained by the Guttural Lowering rule.

We have considered stems where the first and second root consonants are the consonant ʕ: now we consider root-final ʕ. The data in (62) show examples of verbs whose true underlying imperfective stems are CCV.

The plural suffix /u/ becomes [w] after final a. Although the second consonant is a sonorant, the metathesis rule does not apply in náʔraw because no cluster of consonants containing a sonorant in the middle would result.

Now compare verbs with a medial sonorant where the final consonant is hypothesized /ʕ/. The singular columns do not have any striking irregularities which distinguish them from true CVCV stems.

The prefix vowel is unstressed and in an open syllable, which is found only in connection with metathesis: but metathesis is invoked only to avoid clusters with a medial sonorant, which would not exist in hypothetical *[níblau]. This is explained if the stem ends with /ʕ/. Thus /ni-smiʕ-u/ should surface as nisímʕu, by analogy to /ni-tlob-u/ ! [nitólbu] ‘we ask.’ The consonant /ʕ/ induces lowering of the vowel i, and ʕ itself becomes a, giving the surface form.

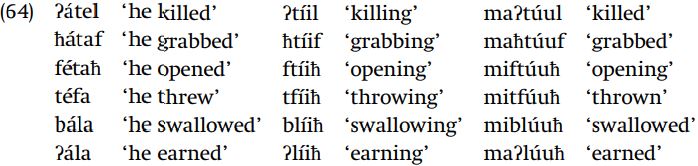

A final set of examples provides additional motivation for assuming underlying ʕ. Participles are formed by giving the stem the shape CCVVC, selecting either ii or uu. As the data in (64) show, stems ending in the consonant /ʕ/ realize that consonant as [ħ] after long high vowels.

These data provide evidence bearing on the underlying status of the abstract consonant, since it actually appears on the surface as a voiceless pharyngeal in (64). Although the forms of the participials [ftíiħ] and [tfíiħ] are analogous, we can tell from the inflected forms [fétaħ] ‘he opened’ versus [téfa] ‘he threw’ that the stems must end in different consonants. The most reasonable assumption is that the final consonant in the case of [téfa] is some pharyngeal other than [ħ], which would be [ʕ]. Thus, at least for verb stems ending in /ʕ/, the underlying pharyngeal status of the consonant can be seen directly, even though it is voiceless. Since the abstract consonant can be pinned down rather precisely in this context, we reason that in all other contexts, the abstract consonant must be /ʕ/ as well.

The crucial difference between these examples of abstractness and cases such as putative /ɨ/ and /ə/ in Hungarian, or deriving [ɔj] from /œ̄/ in English, is that there is strong language-internal evidence for the abstract distinction /u:/ vs. /o:/ in Yawelmani, or for the abstract consonant /ʕ/ in Maltese.

الاكثر قراءة في Phonology

الاكثر قراءة في Phonology

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)